Are you losing sleep wondering how the stock market works? Today's your lucky day. We'll impart all you need to know to become a market pro in no time flat.

How do stocks work?

What’s the one thing a stock market needs to operate? Why stocks, of course! So before we tackle the real edge-of-your-seat topic of how the stock market operates, let’s start by defining our terms.

What the heck is a stock? A stock represents a share in a company’s ownership, and those who own stocks can claim a percentage of the company’s assets and earnings. Exactly what percentage depends on how many shares you own relative to how many currently exist — or in finance speak, the “outstanding.” With some simple division, we learn that a stockholder who owns 100 shares of a company with 5 million outstanding shares owns .00002 of the company. (Don't let it go to your head, Mr. Bigshot.)

A company will issue stock in order to raise money for various business-y reasons — the most prevalent of them being expansion that the company wouldn’t otherwise have the cash to undertake. When the company first issues shares, they often do so through what’s called an initial public offering, or IPO. Since it’s the first time they’re sold, this is called a stock’s “primary market.”

Once the shares have been sold that first time, stockholders will need a place to resell them, kind of like a used-car lot for stocks. This is called the stocks’ “secondary market,” but it’s more familiarly referred to as just “the stock market.”

The vast majority of all stocks are listed on one stock exchange, and there are 60 major stock exchanges globally; the top 16 are often called “The $1 Trillion Club” since the market capitalization of its component stocks tops $1 trillion. The stocks traded on the $1 Trillion Club represents 87% of all global market capitalization, and the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), with its 18K+ listed stocks, is the megalodon of global exchanges, representing almost $30 trillion in market cap. (The poor little Malta Stock Exchange, with just four stocks listed on its exchange, is destined to forever have its nose pressed against the $1 Trillion Club’s window). The ten biggest stock exchanges in the world are listed below:

Name | Location | Market Capitalisation (USD) |

|---|---|---|

| New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) | USA | 25.53 trillion |

| NASDAQ | USA | 11.23 trillion |

| Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE), also known as Japan Exchange Group | Japan | 5.1 trillion |

| Shanghai Stock Exchange (SSE) | China | 4.67 trillion |

| Hong Kong Stock Exchange (SEHK) | China | 4.23 trillion |

| Euronext | Netherlands | 3.67 trillion |

| Shenzhen Stock Exchange (SZSE) | China | 3.28 trillion |

| London Stock Exchange (LSE) | UK | 3.2 trillion |

| TMX Group, includes the Toronto Stock Exchange (TSX) and the Montreal Stock Exchange | Canada | 1.75 trillion |

| Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) | India | 1.51 trillion |

Even though a stock is listed on one exchange, it could be available for purchase on other exchanges. Depositary receipts are clever ways that banks list stocks on other exchanges than their home exchanges. For this reason, a Cleveland-based Honda Accord enthusiast (and yes, there’s a club for this) may use a broker to buy Honda Motor Company stock (symbol: HMC) on the NYSE through an American Depositary Receipt (ADR), even though it’s listed and primarily trades on the Tokyo Stock Exchange.

How the stock market works

The stock market works pretty much the same that it’s always worked, but it looks a lot different today than it did 50 years ago. Since computer automation now represents the vast majority of trading activity, markets like the NYSE, which was once a mosh pit of blue-coated traders shouting and gesticulating, are now relatively sedate. Working stock exchanges are rapidly going the way of drive-in theaters and video stores; the markets continue to trade online, but the actual physical stock exchanges in London, Hong Kong, Tokyo, and Singapore have shut down altogether.

The stock market allows buyers and sellers to trade stocks listed on a particular exchange, mostly online and through licensed brokers.

Regular folks can’t just show up at the NYSE to buy a share or two of Apple. They have to employ the services of licensed middlemen—brokers — to buy stocks. In all likelihood this broker is not a living, breathing broker named Tony who lives with his family in Hoboken, but rather an electronic institution like Wealthsimple. A few brokers still exist on the floor of the NYSE, and they buy their stocks from Designated Market Makers, or DMMs, people who preside over the orderly selling of a specific list of publicly traded companies.

How is the price of a stock determined?

Like any other free market, the stock market works according to the laws of supply and demand. Supply refers to how much of something is available, and demand is how much of it consumers want to buy. Excess demand will drive prices up, and excess supply will push prices down.

Investors may determine the price of a stock based on a number of factors, which include:

Revenue growth

Historical price

Earnings per share

Price/earnings ratio

Dividends

How stock picking works

It’s not easy picking stocks by simply researching how they’re priced as it relates to their revenue growth, historical price, etc., and attempting to pick up some underpriced bargains. Buying stock is nothing like walking into a store and finding a gorgeous $1,000 suit on sale for $200. Through the law of supply and demand, the market has already worked all its special price discounting magic and all of the information the market knows is already baked into a stock’s price. So unless you get some inside information from someone inside the company — a practice called insider trading, which will land you in the pokey and get you featured among the un-savories on a list like this one — understand that in stocks, you get what you pay for.

Two parties are required for a stock market sale: a buyer and seller. At the time of a sale, sellers are trying to sell stock for as much as they can, and buyers hope to pick up the stock dirt cheap. Sellers decide on the absolute lowest price they’d accept to part with the stock and buyers the highest they’d pay to buy it. The amount that divides these two numbers is called the bid-ask spread. Naturally, the closer the bid-ask spread is to 0, the more the stock will be traded, a condition called liquidity. How much a stock is traded on a particular day is referred to as its “share volume.”

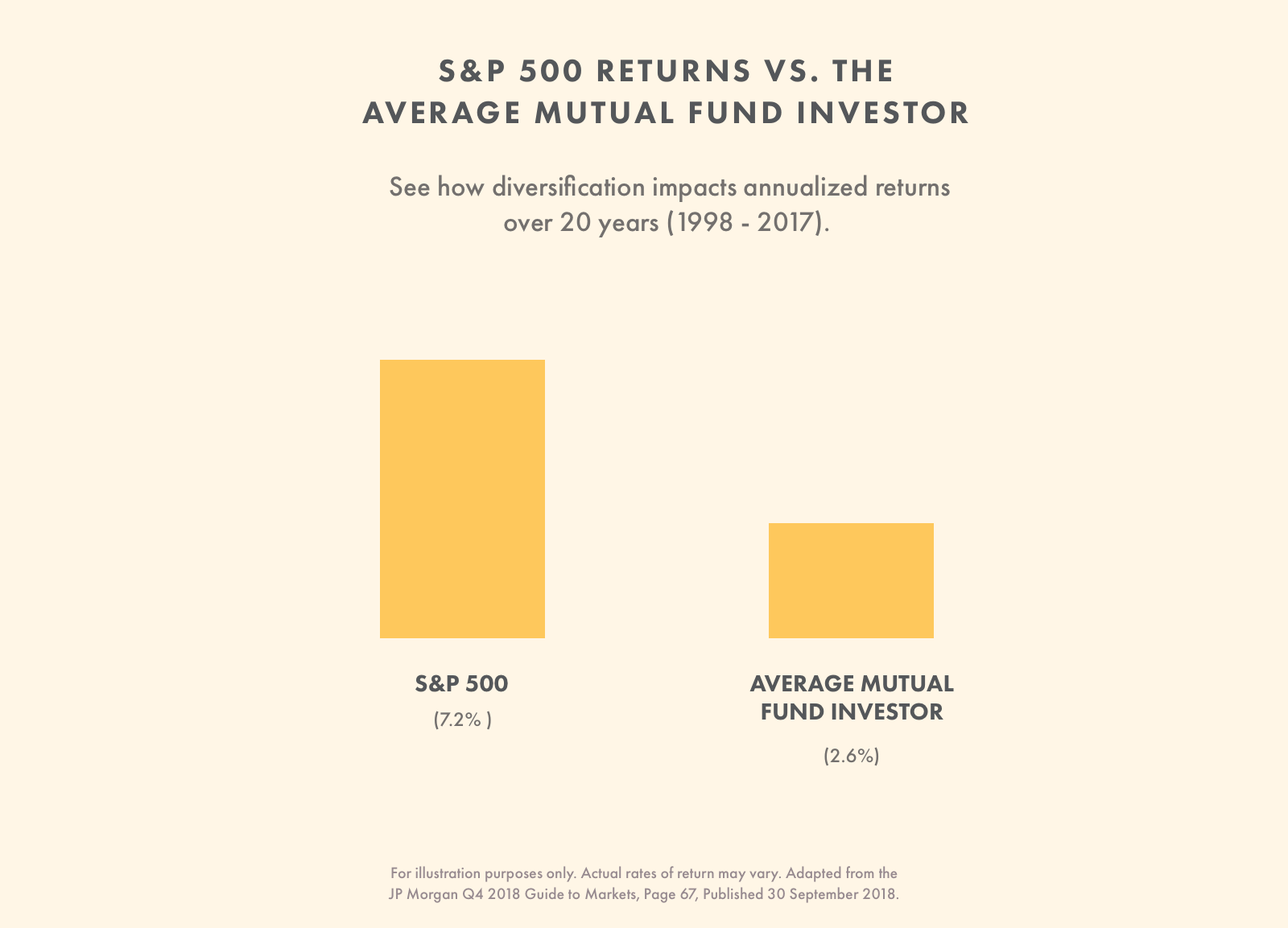

If you're the buyer, how sure are you that you’re smarter than the seller? Here’s the tricky philosophical quandary that makes buying stocks a difficult business, and one of the reasons that the vast majority of those who are paid handsomely to pick stocks fail to outperform the stock market as a whole.

You, the person who wants to buy a stock, are doubtlessly super smart. But when you buy a stock, you have to buy it from someone. That person might be super smart, too, and they have access to exactly the same information you have (or, if they’re breaking the law and engaging in insider trading, significantly more). They have decided the stock is worth selling at say, $10 a share because it's definitely going to go down, and you’ve decided it’s worth buying at that price because it's definitely going to go up. Who’s right? How sure are you that you’ve synthesized all the available information better than other investors? No offense, but what makes you so darned special?

Advantages of investing in the stock market

Depending on which source you consult, you’ll hear a variety of numbers quoted of how much the stock market has grown on an annualized basis. Some sources may run a bit higher, others may be lower, but all of them will show that over the long haul, the stock market has provided very good returns on investments.

So naturally the advantage of investing in the stock market is you have the potential to make quite a bit of money if you invest over a long period of time, a lot more than if you invested in safer bets like fixed-income government bonds. A compound return calculator will show that if $100,000 is left alone for 30 years, based on a 9.5% rate of return, it would grow to about $1.7 million. Be warned though: Investments are speculative, and it’s important to understand that past results should never be understood to be guarantees, but rather imperfect predictors of future performance. While you have the potential to make money on stocks, you could also lose money (that's the not so nice part). Mark Sette, a Certified Financial Planner and advisor at Wealthsimple, points out that offsetting the risk of involution devaluing your money is another major advantage of investing. Sette goes on to point out that if you had $100K sitting in cash for the past 10 years, it would now only feel like $70K today, in terms of purchasing power. He cautions that while history is not an indicator of future results, investing in the market helps to offset this risk.

So far, we have provided lots of sobering information about the difficulty of stock picking and about how investing in stocks is risky and it’s quite possible that you could lose not only your shirt, but your socks and underwear, too, by investing in a stock that tanks. But risk also happens to be the reason why stocks make a lot more money than “safer” investments like government bonds. There’s a concept called the “equity risk premium” (ERP), which is the percentage over the so-called “risk free rate,” or the current interest rate you could get by putting your money in risk-free government bonds. Over the long term, investors will expect to be rewarded for taking on risk. This concept keeps stocks viable; if a stock wasn’t expected to outperform the risk-free rate, investors would just stick with the safe money and a stock price would crater. So one of the most important responsibilities of a company’s CEO is to do everything they can to make sure that investors get bigger rewards, in exchange for their risk, than they would parking their money in something safe like bonds.

There happens to be a pretty good alternative to picking individual stocks to harness the growth of the stock market while limiting the crushing loss that happens when a stock tanks. Harry Markowitz, the Nobel Prize winning economist who championed an investment strategy called Modern Portfolio Theory, posits that the key to effective investing is diversification — acquiring not just a big holding in one or two stocks, but rather buying dozens, or even better, hundreds of smaller holdings in many, many stocks. There are many reasons why diversification is the most cunning strategy of all. By investing widely, the theory goes, you’ll enjoy robust stock market results while protecting yourself from crushing downsides when a specific stock or sector falls precipitously.

How do I invest in the stock market?

You have a number of choices when it comes to investing in the stock market. The main choices are an online brokerage, a human stock broker, a financial advisor, or a robo-advisor.

Online brokerage

The absolute easiest, cheapest way to buy stocks is through an online discount brokerage. Accounts can be opened in 10 minutes if you have a social security or social insurance number, a home address, and an employer’s address (don’t freak, freelancers — it’s totally OK if your office happens to be five feet from your bed). Discount brokerages normally charge a fee for each stock, mutual fund, or ETF you trade. Most will assess a flat per-trade commission fee for any stock purchase, big or small, that generally ranges from $5-$10 per online trade. Increasingly, a few investment providers have started offering commission-free trading, so every cent you pay goes directly into your stock investment, rather than the brokerage’s coffers.

Financial advisor

If you have a financial advisor, you may choose to execute trades through him or her. Some advisors are “fee-only,” meaning they’ll either charge you a flat fee or take a small percentage of the value of your portfolio every year. If you don’t have a financial advisor, it might not be best to hire one specifically to make a single trade. Advisors generally specialize in creating financial plans that help with the bigger picture. They are particularly useful for people with a high net worth or complicated tax situation. If that's you — then you'll be well served getting a financial portfolio review with an advisor.

Robo-advisor

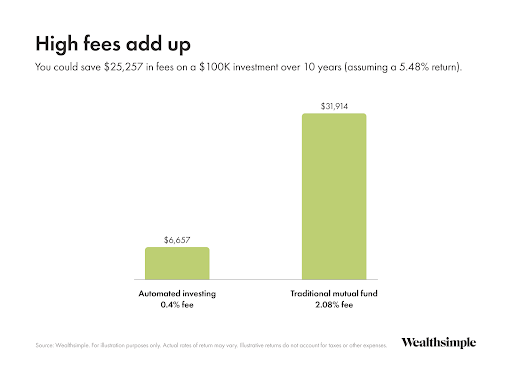

Generally, automated investing services will put together a diversified basket of exchange traded funds for their clients based on their investment goals rather than individual stocks. (Our patron saint, after all, is Harry Markowitz.) The advantages of robo-advisors come in the form of low fees and a diversified portfolio that's likely made up of a bunch of different stocks, bonds, and real estate.

Robo-advisors generally aim to track the market rather than beat it. It's generally straightforward to sign up for an account with an automated investing provider, everything is done online, and you can start investing in minutes.