Like stocks, bonds are a way to connect institutions who need money with lenders who have it. Only instead of giving investors equity in the company like a stock does, bonds are simple loans. They earn regular interest payments until the end of a predetermined amount of time (when the bond “matures”), at which point the issuer pays back all the money it borrowed.

How bonds work

Investors can hold onto a bond, collecting interest and waiting for that final payment, or they can sell it to someone else. The amount of money they’ll get depends on the bond’s interest rate, the time left until it matures, and other factors.

Basically, the price of a bond is the value, in today’s terms, of all future payments from the borrower (the remaining interest payments plus the face value of the bond).

In a portfolio, bonds typically act as a diversifier against stocks and other riskier assets. That’s because bonds react differently to different economic environments. So in instances when stocks take a nosedive, bonds can often buoy a portfolio by continuing to deliver a relatively safe return.

How bond interest rates are set

You’ve got a lot of ways to grow your money. Stocks, bonds, alternative assets like private credit or real estate, or simply putting your cash in an interest-bearing account are all ways to generate a return. The size of that return all depends on one somewhat scary principle: risk.

Think of it as hazard pay. Anyone selling an investment needs to convince you that giving them your money will be worthwhile in the end. The more likely you are to lose your money, the higher the reward needs to be.

Bonds need to offer enough interest to account for two risk factors:

Opportunity cost. Lenders may find more attractive options for their money.

Credit risk. The borrower may be unable or unwilling to pay back the loan.

These two factors determine the initial interest level on a bond. But when one or both change after the bond is issued (interest rates go up or down, or the lender’s stability changes), since the interest rate is set, the value of the bond itself changes. If you lend money today and realize tomorrow that you could have gotten a better deal elsewhere, the value of the original deal drops.

How risky are bonds

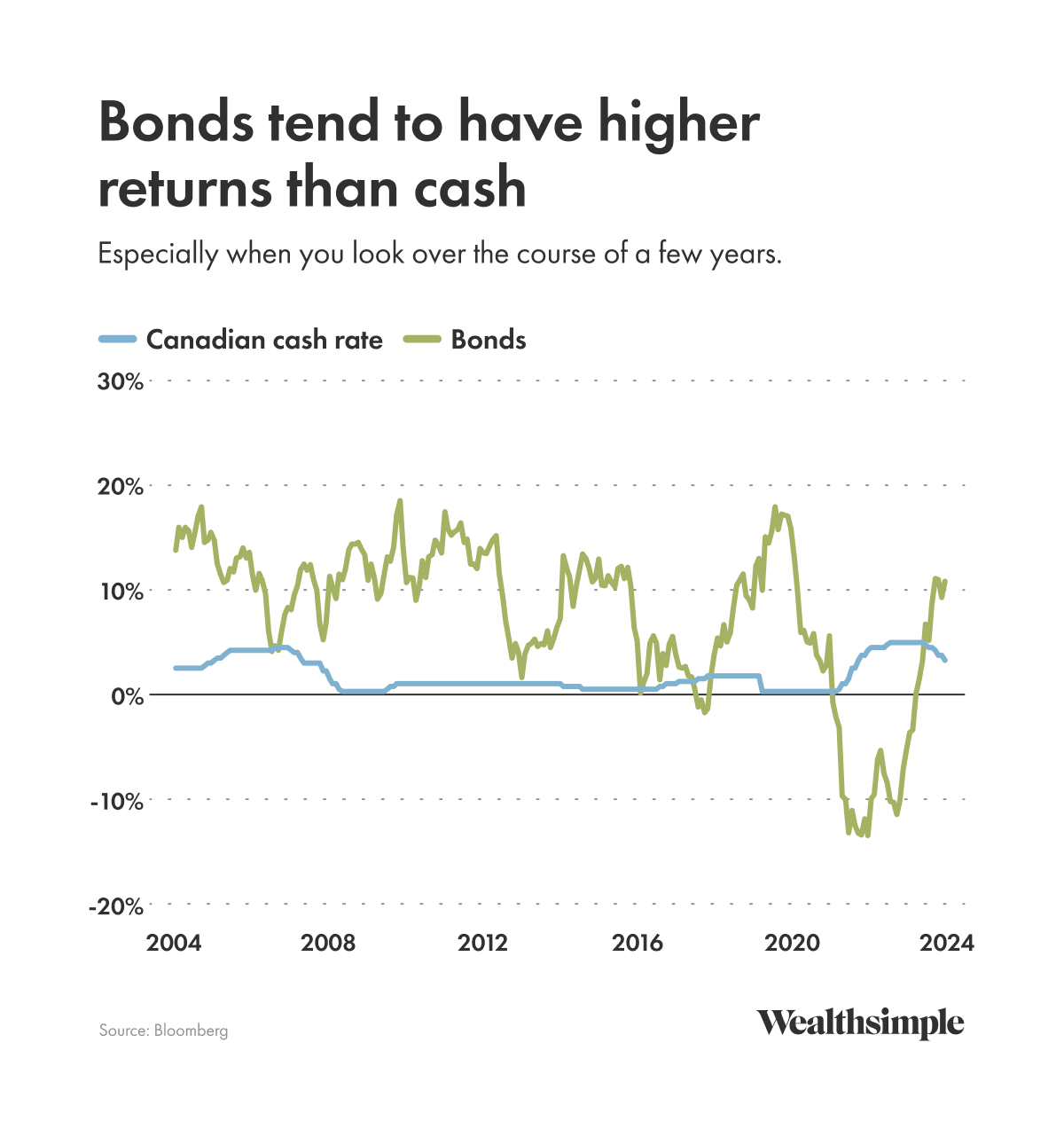

On the spectrum of risk and return, bonds tend to sit between cash (the short-term interest rate set by central banks) and stocks.

Asset | Approximate expected returns | Economic conditions it tends to do well in | Economic conditions it does not tend to do well in |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cash | 2% - 3% | High interest rates | Low interest rates |

| Bonds | 2% - 4% above cash | Low growth, low interest rates, recession | High growth, high interest rates, high inflation |

| Stocks | 6% - 10% above cash | High growth, low interest rates, economic boom | Low growth, high interest rates, recession |

| Private credit | 4% - 8% above cash | High growth, high interest rates, economic boom | Low growth, low interest rates, recession |

Bonds have about an 80% chance of outperforming cash over the course of a few years. The past performance of the Bond ETF portfolio and any other security or investment strategy is not an indicator of future performance, and past performance may not be repeated. Comparison is for informational purposes and does not constitute investment advice. All investments involve risk.

Types of bonds

There are all sorts of different bonds out there, each with their own issuers, duration, and risk level. But here the types that you, a person who does not sit at a Bloomberg terminal all day in the comfort of a Patagonia vest, are most likely to come across:

Government bonds

Whenever governments need money for a big project, like building a new highway (or a tunnel under a highway) they raise cash by issuing bonds. A lot of bonds. As of the end of 2024, the Canadian government had $1.3 trillion in outstanding bonds on its books. Generally speaking, the richer or more politically stable the issuing country, the lower the bond yield. Just remember that while government bonds are very low risk, they aren’t totally guaranteed. Even the U.S. government had a technical default in 1979, forcing it to miss treasury bond payments for a few weeks. And some governments will just print the extra money they need to pay you back, driving up inflation in the meantime.

Government bonds have historically delivered returns in excess of cash. Even when they don’t, they can still be very helpful as part of a portfolio, since they tend to diversify stocks when the economy struggles.

Corporate bonds

Big companies like Coca-Cola, Warner Media, or CVS Health also issue bonds to raise cash, usually to fund projects or pay down debt. While they’re usually much less risky than stocks, credit rating agencies consider corporate bonds to be on a tier below bonds issued by rich countries like Canada or the U.S. That extra risk tends to turn into higher yields.

Provincial and municipal bonds

National governments aren’t the only ones who raise cash through bond sales. Provinces like Saskatchewan and Quebec, as well as major cities like Toronto, also issue bonds with credit ratings similar to the Canadian or U.S. governments. The details on these bonds vary a lot, but most require at least a $5,000 investment. They perform pretty similarly to government bonds, but can earn a bit more in yield because provinces and cities aren’t quite as financially self-sufficient as Ottawa: provinces don’t have central banks, and Canadian cities aren’t allowed to run deficits.

High-yield bonds

High-yield bonds are notably riskier than corporate or government debt. Their issuers tend to be companies who need cash more urgently and may have trouble securing traditional bank loans. To sweeten the deal to wary bondholders, these companies throw in higher yields to make up for the extra risk that comes with tying up your money with them.

How does bond pricing work?

The interest payments and face value of bonds are determined when they’re issued, based on opportunity cost and credit risk. But the market price changes constantly.

Let’s say you buy a new 10-year government bond with a face value of $1,000 and a 4% coupon rate. If interest rates fell to 2% the next day, new bonds would pay out only half as much as yours, which means the value of your bond would go up. If, however, interest rates doubled to 8%, new bonds now pay twice as much in interest as yours, and the value of your bond would go down.

Why investors care about bonds

Even if you don’t dream about yield curves or get excited when the Fed issues a new Treasury bill, we think you should pay attention to the bond market. Here’s why:

Government bonds can offset stock volatility

In bad times, corporate earnings are usually in the dumps, so stocks aren’t a great bet. That’s why government bonds that are more or less guaranteed to earn money come out on top. A small return is better than a loss, after all! Corporate bonds, on the other hand, tend to get killed during recessions because companies get tight on cash, which can result in skipping out on their debt (including bond payments).

Speaking of corporate bonds, they can indicate when a recession is coming

When cracks start to show in economic performance, corporate bond prices tend to change faster than stocks. The credit spread between stable bond issuers (rich governments) and unstable ones (telegraph companies) usually widens, which suggests these bonds are riskier to hold. If that happens, pay attention. Bonds are basically the smoke detector of global capitalism. When the bond market starts shrieking, stocks usually aren’t far behind - even if you’re convinced nothing’s burning.

Bonds stabilize a portfolio

Stocks are great growth assets for any portfolio, but there is a downside to going all stocks, no brakes. Eventually, you hit a wall. Portfolios with 60% stocks can actually perform better than an all-stock portfolio over a five-year timeframe. Bonds are one way around this problem. They don’t bring in the same returns as stocks, but a portfolio with a healthy bond allotment won’t completely tank if the stock market crashes.

Bonds tend to do well during high interest rates

Unlike stocks, which tend to slump during periods of high inflation, bonds usually thrive. When central banks raise interest rates to cool down the economy, bond yields remain the same. If the James Bond Company drops a bond with a 5% yield on Monday and the Bank of Canada hikes the overnight interest rate to 6% on Tuesday, that bond suddenly doesn’t look too attractive. The James Bond Company might issue new 6% bonds on Wednesday to keep its bonds attractive…but the bonds it issued on Monday are still at 5%. That means its yield to rise — because its annual payment is now split across a smaller total. 5% of $100 is $5, but if a bond’s price drops to $90, you’re now getting $5 a year on a bond that should only get $4.50.

How bonds can help your portfolio

First off, you can’t guarantee any portfolio mix is going to save you in bad times. Markets are never certain. The easiest way to protect your portfolio is to invest in a wide range of assets, but even diversification isn’t quite the same as reducing your risk. Junk bonds can be pretty risky. Utility stocks are boring, but can be pretty safe investments.

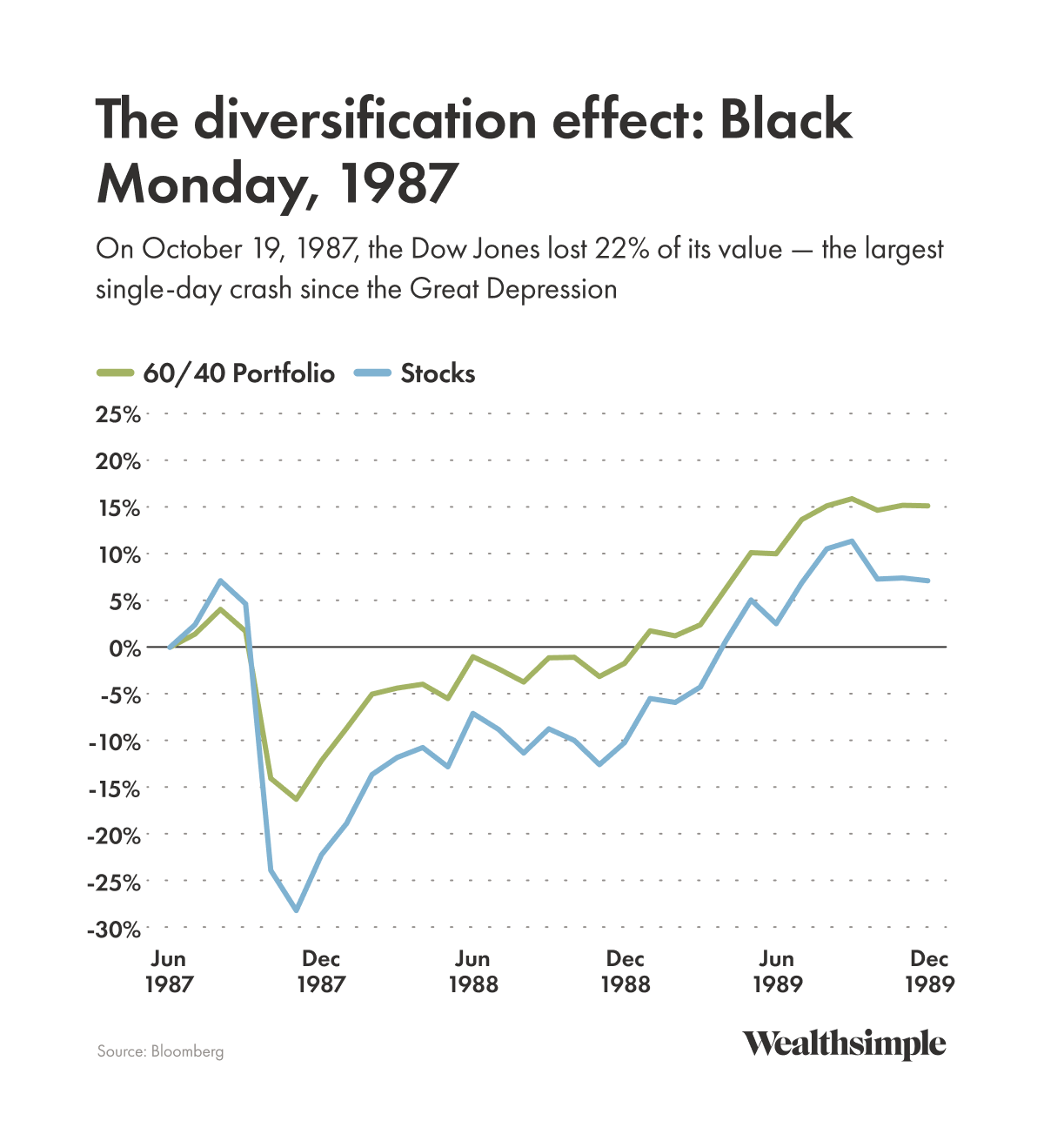

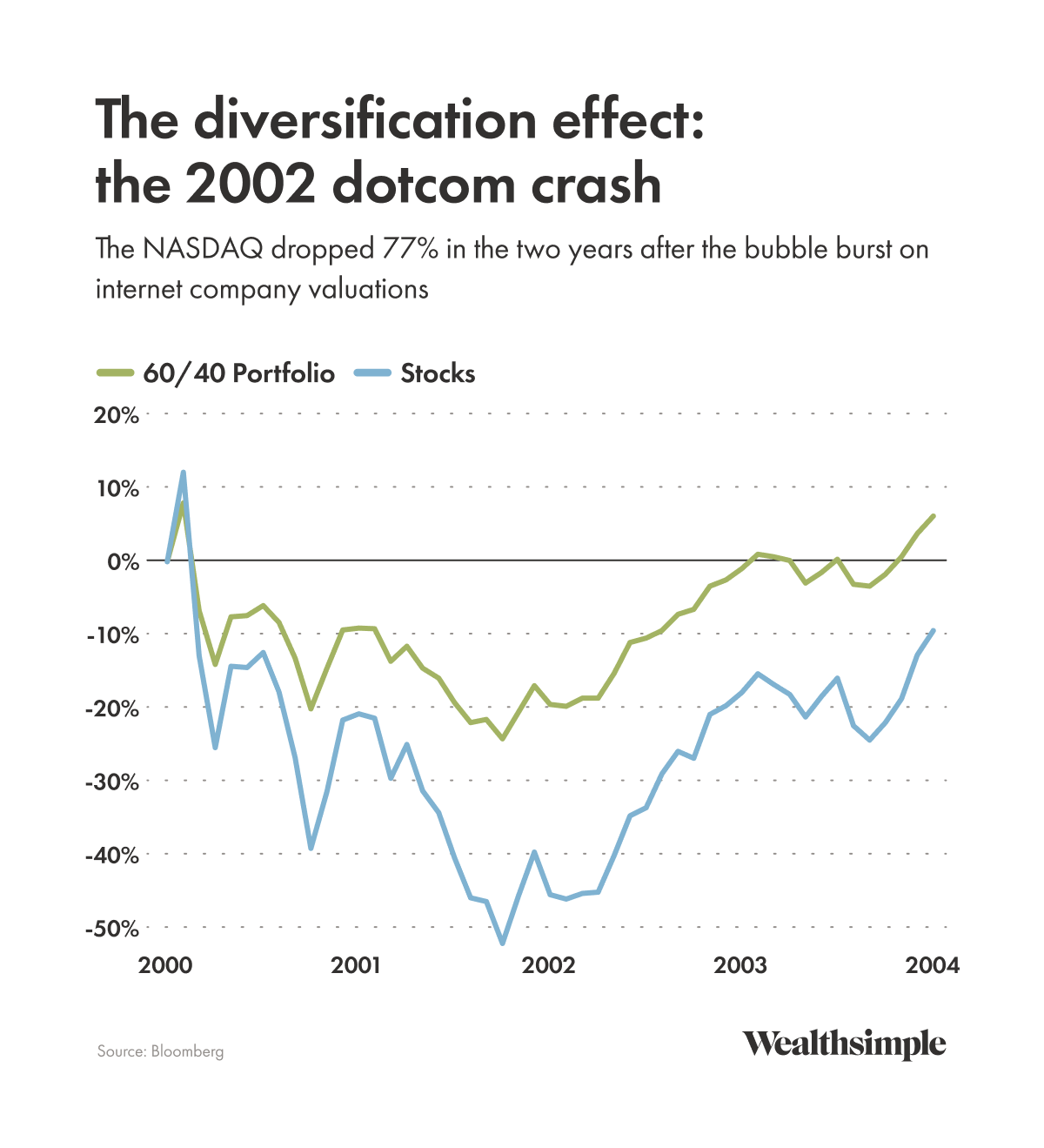

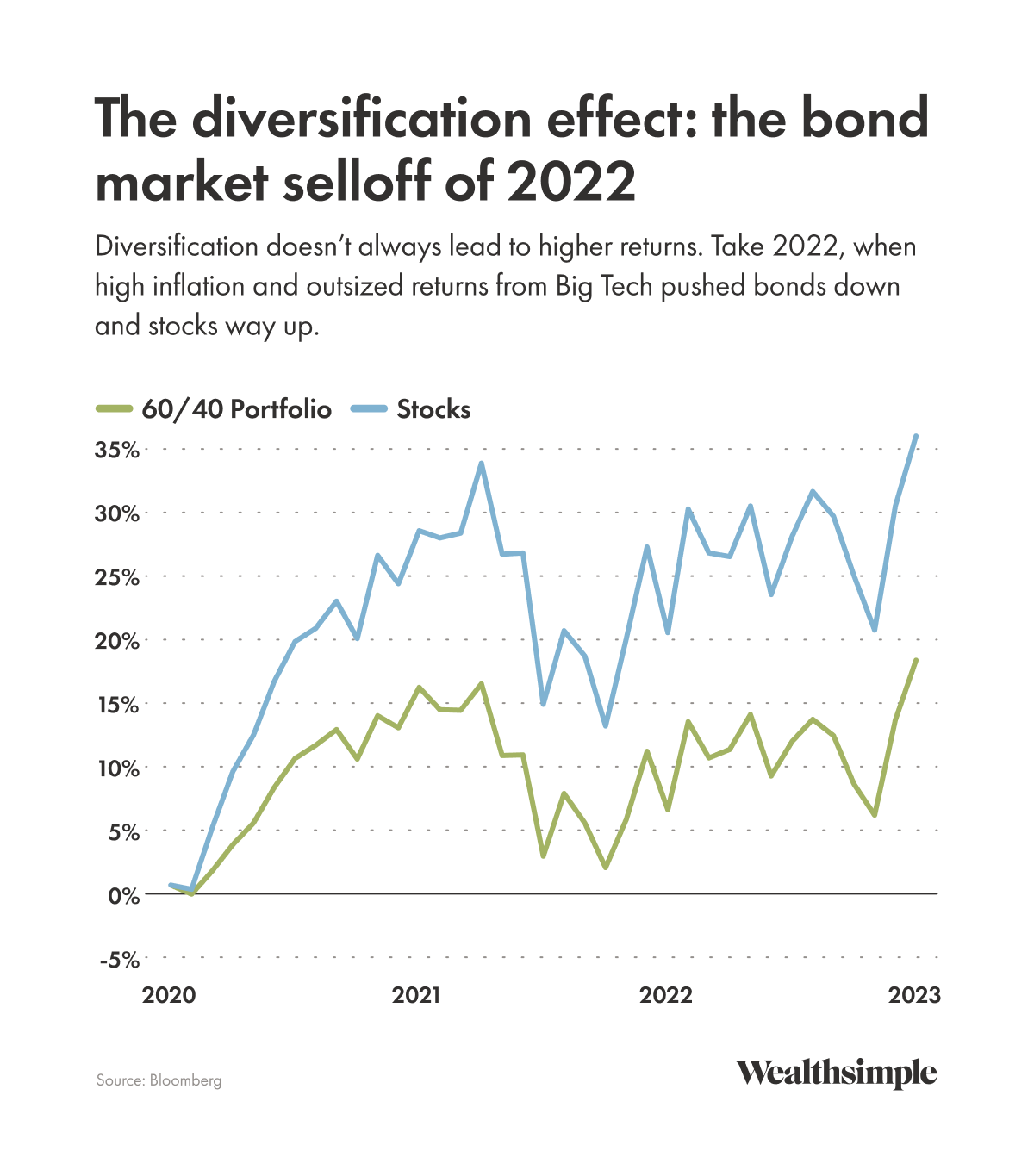

All of that said, holding bonds is one way to ensure your portfolio isn’t tossed around during a market crash like a toothpick in a tidal wave. The following charts simplify things a bit to take risk out of the picture, but show you how a good old-fashioned portfolio of 60% stocks and 40% bonds performed compared to an all-stocks-no-brakes portfolio in various moments of market turbulence.

1987 - Black Monday

Without getting too far into the details, Black Monday was a bad day for investors. The Dow Jones lost 22% of its value in just one day, the largest single-market crash since the Great Depression. As you can see, the 60/40 portfolio dropped 5% in the final months of 1987, but the all-stock portfolio looks like it skidded off a Formula One track and smashed into the barrier wall, hard.

2000 - Dotcom crash

Another not-so-great time for stocks (or anyone in tech for that matter). Once upon a time, Wall Street thought .com addresses were money-printing machines. The resulting bubble reached its peak in 2000, then popped violently. Trillions of dollars in valuation was wiped out over the following two years, with the NASDAQ plummeting 77%. No one’s having a great time in the stock market, as you can see, but the 60/40 portfolio is cruising along. Perhaps its engine is on fire, but it’s still moving at least.

The all-stock portfolio? Not so much.

2022 - bond market selloff

Here’s an interesting counterexample. U.S. stocks have been on an absolute tear since 2022 without any obvious signs of a serious crash ahead. Thanks to high inflation and outsize performance from seven U.S. tech companies (aka the Magnificent Seven), the 60/40 portfolio is motoring at a respectable speed, but with a healthy set of brakes should the market crash. The all-stock portfolio, careening around the track, looks like it’s trying to die historic on the Fury Road.

Where do I buy bonds?

As complicated as bonds can seem, they’re not hard to find. Here’s a rundown of the most common ways to get your hands on a bond:

Through a managed bond portfolio

Let the professionals find an ideal mix of bonds to suit your financial goals. You don’t need to know anything about shallow yield curves or private credit. Just invest.

Pros: You get a tailored financial portfolio handled by someone who’s a finance geek. Sit back and watch the coupon money trickle in.

Cons: You don’t have a lot of control over exactly which bonds are in your portfolio. And you’ll need to pay management fees.

In a bond ETF

You can also pack an assortment of bonds and other fixed-income assets into an ETF, just like a mutual fund, but ETFs usually charge lower fees. They’re pretty easy to find through a brokerage, too.

Pros: It’s a big juicy sandwich that can hold bonds of varying maturation dates, issuers, and risk levels. Trades all day rather than once a day like a mutual fund. Great for diversifying your bond holdings without getting mustard on your shirt.

Cons: A bond ETF tracks a range of issuers, so it won’t generate huge returns if a bond starts doing really well. And while it does diversify your portfolio, a bond ETF on its own will take losses if the bond market sinks.

Directly from a seller

Go to the Bank of Canada, or your provincial or municipal government, or whoever happens to be selling the bond you want. Hand over money, receive your bond. If you do it directly through the issuer, you’ll pay the face value. Otherwise, the market value might be higher or lower.

Pros: Pretty straightforward. You can buy as many or as few bonds as you want on the market’s terms.

Cons: You’ve got to do all the work yourself, and you probably won’t get a very diverse mix of bonds out of it.