Get instant help from AI

Call 1-647-584-1344

Wealthsimple's education team is made up of writers and financial experts dedicated to making the world of finance easy to understand and not-at-all boring to read.

Emma Jones is the Director of Options at Wealthsimple with more than a decade of experience in the financial services sector. As a CIRO Registered Options Supervisor, she oversees the operational foundations that power smooth, reliable options trading while dedicating herself to helping everyday investors navigate the derivatives market. Emma is passionate about making options trading more accessible through educational resources and intuitive trading experiences, empowering both new and experienced investors to confidently incorporate options strategies into their investment journeys.

Options trading is a way to potentially profit from the rise or fall of an asset’s price without investing in that asset directly. There are a ton of different options and options strategies out there, but the two most common are calls and puts. Calls give you the option (but not the obligation) to buy a stock at a set price by a set time in the future. Puts are the opposite, allowing you to sell a stock at a set price by a set time.

Options are a type of financial derivative. Yes, that sounds boring. And complicated. But it’s not — not boring, at least. (Definitely complicated. Get ready!) With options, you aren’t limited to simply buying or selling a stock. Instead, you can take a position (and possibly earn returns) on very specific expectations, like how much a stock will move and by when. Options give you more options.

Options are contracts. When you purchase an option, you are buying the right (but not the obligation) to buy or sell a specific stock at a specific price by a specific date.

But there’s so much that can happen before that date. Most options are exchange-traded (as opposed to OTC). They trade on markets, like securities do, instead of directly between investors. Which means, along with the right to buy or sell a particular stock, options holders also have the right to sell the option itself at any point until it expires. Here are a few scenarios:

Say a pretend stock, Kale, is trading at $150, and you think it’s going to go up. You could buy an option that gives you the right to buy $KALE stock for $170 a share within two months (by the expiration date), no matter its price at that time.

If you waited two months and Kale was at $180, you could “exercise” your option, which just means you’d buy the stock at your locked-in rate of $170 and could immediately sell it (at the going rate of $180) for a profit of $10/share.

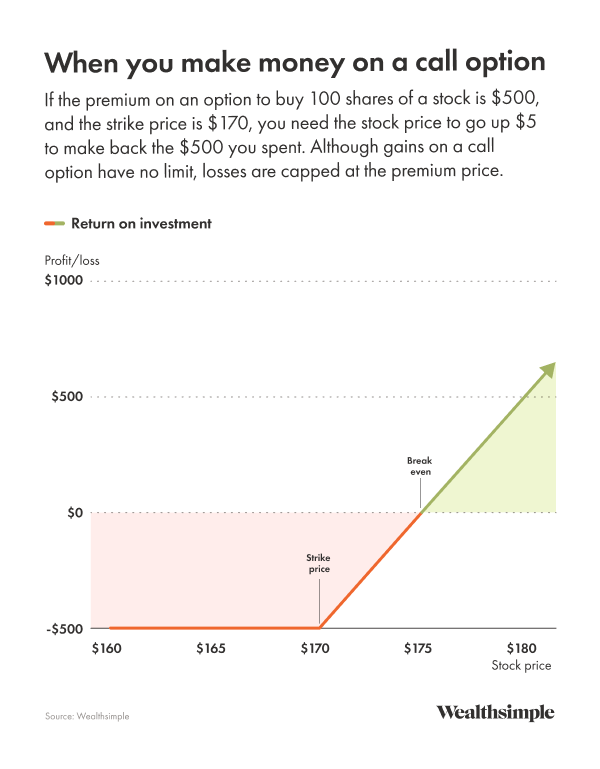

An options contract usually represents 100 shares of the underlying stock, but the price of the option (called the premium) is quoted per share. So in this example, with a $5 premium, those Kale options would cost $500 per contract. After subtracting your $500 premium from the $1,000 you earned, you’d end up with $500 in profit, minus any relevant fees. For comparison’s sake, had you invested that $500 in Kale shares, you’d be up 20%, or $100.

You could also sell the option before it expires. A lot of people do. Say $KALE got to $165 a week after you bought the option. You could potentially sell the option for more than you bought it for, since it’s now closer to the $170 — and closer to making a profit when exercised at the expiry date.

In a less rosy scenario, say $KALE traded well below $170 for those two months. You could sell the option at any point for a loss — someone might be willing to take on the risk. If you held on to it till expiration, though, there’d be no point in exercising your option and you’d lose your $500.

Here’s an easy way of visualizing your potential profit or loss in this scenario.

You want to hedge your risk. Say you own a lot of Kale stock and you're worried the price could fall. Buying a put could limit losses if that prediction comes true.

You want to get more exposure without spending a lot of money. Buying options can be a lot cheaper than buying corresponding stock outright, and the leverage provides a much higher potential upside.

You have studied the market and want to play your hunches. Instead of simply choosing between whether a stock will go up or down, options can be used to profit off of predictions of how much a stock will move and by when.

Call options give you the right to buy a stock at a certain price (called the strike price) on or before the expiry date. They’re useful if you think a stock is going up, because they let you buy shares for what could be less than the market price. (See our handy glossary of terms.)

Put options give you the right to sell a stock at a certain price on or before the expiry date. They’re useful if you think a stock is going down, because they let you sell shares for what could be more than the market price.

The majority of the most popular securities have options available to trade on them. Of the more common options, you’ll also see single stock options, which are (surprise!) options that relate to a single stock (e.g., Apple, Google, Amazon), and ETF options — options that relate to … ETFs (groups of stocks).

Let’s go back to the Kale example. You could sell that option up until the day it expires. What you could sell it for depends primarily on the price of the underlying stock.

If $KALE tanked, falling way below the strike price a few weeks after you bought your option, you could sell it, but you’ll likely get less than the $500 you paid, since the option would be less likely to pay off. If $KALE is way above the strike price and there’s only a week left till the option expires, however, the option has a high chance of making money, and you could likely sell it for a lot more than $500.

You could also wait till the expiration date. (Another also? You could exercise the option early. We’ll get to that in a second.) If $KALE is above $175 that day, you could exercise your option, cover the premium you paid, and pocket the difference. If you get to the expiration date and the stock is below $175, however, you will lose some of the $500 you have paid.

In this example, $175 is known as your “breakeven” — your strike price plus the cost of the option. If $KALE only reaches, say, $172, then your option will be “in-the-money” (when the stock’s current price means you would profit if you bought or sold at the strike price) by $200. But you would still be down $300, since you paid $500 for the option.

$KALE tanked, you’d likely sell for a loss (but potentially recoup part of what you originally paid). In the case where $KALE rose, you’d likely sell for a profit. In either case, it’s a way of seeing similar returns without needing bags of cash lying around.

Assuming you have enough money to buy the underlying stocks (for a call) or enough stock to sell (for a put), options can be exercised at any time. It’s usually in an investor’s best interest to wait until the expiration date when any “in-the-money” options will be auto-exercised if you have adequate funds in your account by market close.

If your option isn’t “in the money,” exercising it means locking in your losses. Even if an option is in-the-money, exercising it early means you lose out on the potential for the option to keep increasing in value if the stock price rises.

If your option expires “out of the money,” you’re out of luck. You lose whatever you paid for it.

Like any other market, it depends what people are willing to pay. Figuring that out is complicated and abstract, but it’s essentially driven by three things:

Intrinsic value, or how much the underlying stock price needs to move for the option to be in the money. In the Kale example above, you have a call option that would let you buy 100 shares of $KALE at $170. If $KALE is at $120, the option is worth a lot less than if $KALE is at $168. And if the stock is already at $175, the option is worth even more.

Volatility, or how much the stock price tends to change. $KALE doesn’t have much volatility; it’s been a steady mountain climber, with a few dips here and there. If it’s at $120 and you need it to get to $170, there’s not much chance of that happening before the option expires. A stock like DraftKings, however, has a price chart that might as well track a stressed bumblebee. Even if the strike price is still far away, a stock like that has a much better chance of getting in the money. Which means the option will cost more.

Time value, or how much time until the option expires. The more time you have, the more time there is for the underlying stock price to change — and the more valuable an options contract is.

The specific metrics for pricing options are called “the Greeks.” You’ll see them listed with every options contract, and how they are calculated is pretty 🤓.

🛑 This is important, because the risks are big: if the stock underlying your option doesn’t hit its strike price and you can’t convince someone to take it off your hands before it expires, you lose whatever you paid for it. That’s 100% loss, which is an incredibly rare occurrence in typical stock trading.

Here are some of the reasons options can be riskier than stocks:

Compound volatility. Since options are derivatives of stocks, you’re stacking one layer of volatility on top of another (a stock price is loosely based on predicting a company’s future performance, and an options price is loosely based on predicting a stock’s future performance). That makes it very hard to predict what will happen with the price of an option. For example, if you buy an option with high volatility, something could happen that makes investors’ perception of the underlying asset’s volatility drop. Then, the value of your option can drop, too — even if the underlying asset price stays the same. This happens because the lower implied volatility means the stock’s future movement is more certain. And not a lot of people want to bet against something certain. You may have paid $100 for that option a week ago, but now it could be worth $5.

Time sensitivity. You can hold a stock forever. An option, not so much. As an option’s expiration date approaches, its value can change really quickly. If you’re in the money or close to it, the value shoots up. But if you’re still a long way off, that value can fall off a cliff. Why? The shorter an option’s duration, the less time there is to recover from sudden movements — and the riskier that option is. So, pay close attention to timing.

Confusion. Options are complicated. In a world where it’s normal to hear things like “vol crush” and “the modal outcome is zero,” it’s also normal to get confused. There are a lot of different strategies and techniques to learn, especially when you’re starting out. As you learn, you’re going to make mistakes, and those mistakes can cost you. That’s especially true in the fast-paced world of short-duration trading.

Variable liquidity. There are a lot of stocks out there, but there are exponentially more stock options. Each stock or ETF could have dozens of different options, with different strike prices and durations. This array of different options can lead to low supply and demand for any particular one. This could mean being forced to pay a higher price for an option than you might want to. It can also mean having trouble finding buyers when you go to sell, and having to drop your price to do so. In some cases, you could even be forced to hold the contract to expiry and eat the loss.

Wealthsimple’s Learn pages are meant to be educational. Every story is sourced from and vetted by subject matter experts, and produced by journalists with decades of media experience — people whose primary goal is to teach you something, rather than sell you something. While there may be links included in the article about products that are offered by Wealthsimple Investments Inc. (“Wealthsimple”) or one of its affiliates, these articles are not investment advice, a recommendation to buy or sell assets or securities, or any other kind of professional advice. If you are interested in learning about how Wealthsimple products or features work, please visit the Help Centre. If you are interested in knowing which products are offered by Wealthsimple and which are offered by affiliates, we’ve got a page to help you with that, too.