Get instant help from AI

Call 1-647-584-1344

Wealthsimple's education team is made up of writers and financial experts dedicated to making the world of finance easy to understand and not-at-all boring to read.

Emma Jones is the Director of Options at Wealthsimple with more than a decade of experience in the financial services sector. As a CIRO Registered Options Supervisor, she oversees the operational foundations that power smooth, reliable options trading while dedicating herself to helping everyday investors navigate the derivatives market. Emma is passionate about making options trading more accessible through educational resources and intuitive trading experiences, empowering both new and experienced investors to confidently incorporate options strategies into their investment journeys.

Of all the terms you’ll come across in options trading, a put is one of the easier ones to understand. (There are also naked calls, long straddles, long strangles, and so many more that are slightly more complicated — and not always as aggressive as they sound.)

A put basically gives you the right (but not the obligation, which is important) to sell a stock at a particular price (the “strike price”) by a particular date. But before we can really get into the particulars, it’s important to understand options first.

Options are a financial instrument known as a derivative. That means they are based on the price of an underlying stock, but they don’t actually give you any ownership of an asset. Options are traded separately from stocks and have their own valuation based on several factors, including the price of the underlying shares, supply and demand, and how much time is left before an individual option expires.

The price of an option is called the premium. It’s quoted in dollars per share and typically covers 100 shares. (For example, buying a put option with a $5 premium would cost you $500, or $5 x 100.)

When you buy an option, you have the right to buy or sell shares of a stock at some point in the future. Whether or not you exercise that right by actually buying or selling the underlying shares is up to you — and the markets.

Why would you want that right? Options are flexible investment tools that can help you do a few things, like hedging against losses or generating extra income. You can use options to protect yourself against potential price drops in a stock you own, or to lock in a price of a stock you don’t own to ensure you don’t miss out on future gains. And you can sell options to generate income from the premiums.

Buying a put option is akin to shorting a stock, or betting that the stock’s price will decline. This makes it a bearish strategy. But there are two important differences between shorting a stock and buying a put:

A put has an expiration date. A short stock position does not.

A put’s losses are capped; the maximum loss you’ll face over a put is limited to the premium you paid for the option. When you short a stock, however, there’s no cap on how high the price of the stock might go, which means there’s no limit to how much you can lose.

If the stock price drops below the strike price before the expiration date, you — as a buyer of the put and owner of the underlying stock — can exercise your right to sell the stock, above the market price. If you don’t own the underlying stock, the alternative is to sell the put option before the expiration date and earn profits on the premium collected from the sale.

There are a couple main reasons investors buy put options:

Hedge against losses. If you’re concerned about a down market eating into your gains or negatively affecting the performance of your portfolio, put options could give you some peace of mind to close out stock positions as the market experiences a downturn.

Play a hunch that the price of a stock is going to drop. In that case, you’d probably rather buy the option and try to make some profit than try to actively short the stock, which can be risky.

You can also sell (or “write”) a put option. When you sell a put option, you are obligated to buy the stock at the strike price from a buyer if they decide to exercise the option to sell the stock by the expiration date. Your break-even point occurs at the strike price, minus the premium you charge for the transaction.

In this case, you are hoping that a stock price will fall no lower than the strike price you’ve written into your options contract. This is known as a “short put.” You stand to make a profit from the premium you charge for the put option so long as the price of the stock doesn’t fall below the strike price in your contract. If it does, you’re on the hook for purchasing 100 shares of the stock at that strike price (ouch).

The main reason for selling put options is to earn a profit from the premium for writing the options contract, which you collect whether or not the buyer exercises the option.

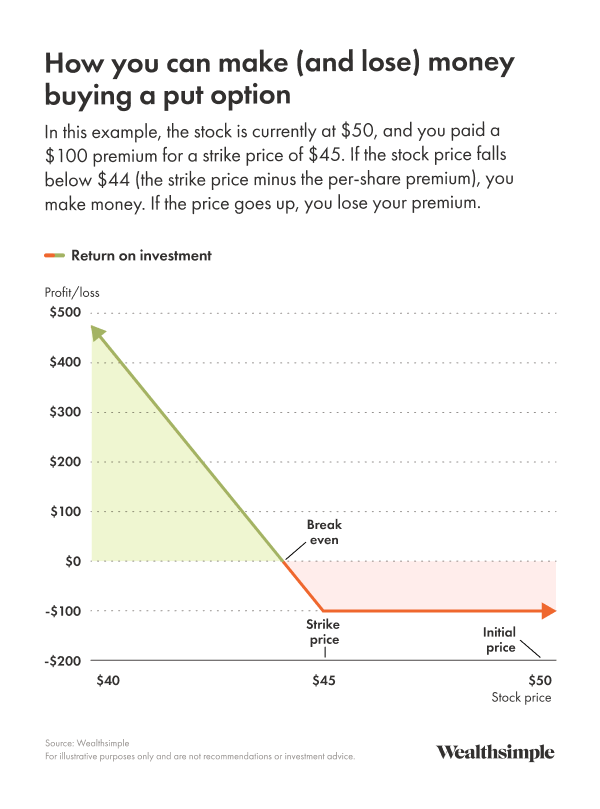

Here’s what buying a put option could look like in practice:

Let’s say you have a stock that’s priced at $50 per share, but because you’ve been studying the market like a good little investor, you think the price could drop to $40 per share in the near future. You purchase a $45 put option for a premium of $1 per share, or $100 total.

Should the stock drop to $40 per share by the expiry date like you predicted, you have the right to sell your shares at $45 each even though they’re currently trading at $40. The seller of the put would have to buy the stock from you at $45, meaning they’d incur a $4 loss per share ($5 difference in the strike and purchase cost, minus the premium of $1 per share they made from selling the option). In this scenario, you’d net a $4 profit per share. Congrats!

And if you bet wrong, and the stock price doesn’t drop below $45 by the expiration date? You lose $1 per share (the premium you paid) and the put option seller keeps the $1 per share as a profit.

Call options are basically the opposite of put options. Call options give buyers the right, but not the obligation, to buy the underlying stock at the strike price by the expiration date. With call options, buyers stand to make a profit when the price of a stock increases.

Where buying put options takes a short position (meaning you’re betting that the stock’s price will decline), buying call options takes a long position: you’re betting that a stock’s price will increase).

There are plenty of different kinds of put strategies (many with weird names, like a bear put spread, or a married put). Covered puts and naked puts are two of the most common. Here’s what it looks like to sell a covered put and a naked put.

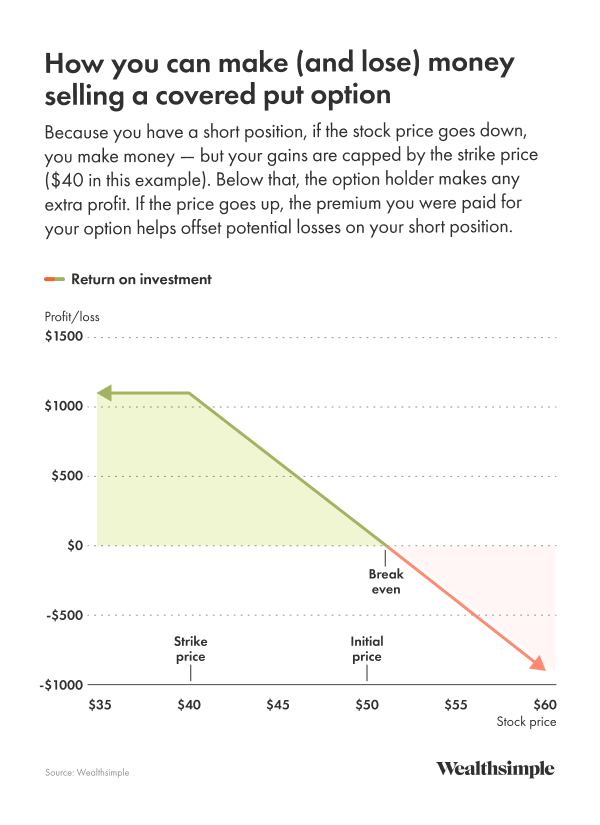

With a covered put, you’re selling the right to sell a stock at the strike price until the option expires — while holding a short position in the same stock. It’s all a bit complicated, so let’s look at an example.

Say a fake stock called $KALE is trading at $50 per share. You have a pretty good feeling that the price is going to fall a lot in the long term, and maybe just a little in the short term, so you decide to short the stock. You borrow 100 shares from a brokerage and immediately sell them for $5,000, with the goal of buying them back later at a lower price to turn a profit. Then you sell a put option of 100 shares. You set the strike price at $40, with an expiry date of 30 days from now. You make a premium of $1 per share upfront just for selling the put option. Here’s what happens based on a few different scenarios:

The stock price drops to $45 The put option you sold expires worthless because the stock price is higher than the strike price of $40. Because you have a short position and sold the stock at $50 per share, you’re going to make a $5-per-share profit, plus the $1-per-share premium you made for selling the put option. That’s a $6-per-share ($600 total) payday.

The stock price drops to $35 At the expiry date, $KALE is $35 per share, which is less than the strike price of $40. The investor who bought your put option exercises their right to sell you the 100 shares at $40 per share, or $4,000 total. Yikes. But wait! That loss is buffered by your short position, which has now gained $1,500. So your total profit would be $1,100 ($1,500 for the gain on your short position, minus $500 for the loss on your put, plus $100 for your initial premium).

The stock price skyrockets to $60 per share The put option you sold expires worthless (because the stock price is now higher than the strike price). You’ve made a profit on the premium, but now you’re underwater on your short position. You can buy back the 100 shares at the new price (this is called covering your short position), locking in a $900 loss (the $10 difference in stock price for the 100 shares you shorted, minus the $100 profit from the option premium). Or you can wait in hopes that the price will come back down again (this is called holding your short position, and it’s risky, since prices could keep going up).

Naked put options

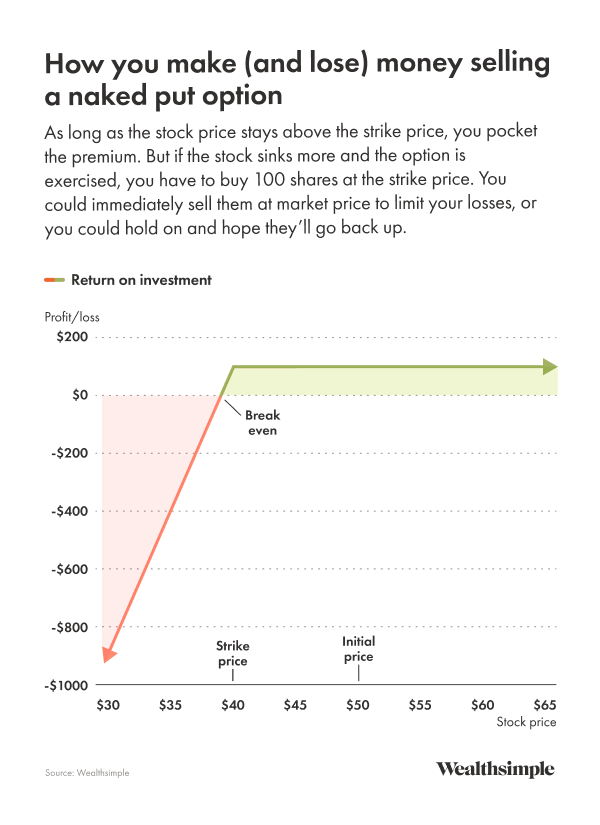

With a naked put, you’re selling the right to sell a stock at the strike price until the option expires. This means that, if the stock price falls, you are obligated to buy the stock at the specified strike price, regardless of its current price. If the stock price rises, there’s no reason for the person who bought the option to exercise it, so you get to keep the premium.

Let’s go back to the $KALE example. Say it’s trading at $50 per share. You’re bullish on the near term outlook, so you decide to sell a put option of 100 shares, at a strike price at $40, with an expiry date of 30 days from now. You make a premium of $1 per share, or $100 total ($1 x 100). When the expiry date rolls around, here’s a few ways it could go down:

The stock price stays above $40 The put option you sold expires worthless because $KALE shares are now more than the strike price of $40. You walk away with the $100 premium you made for selling the put option.

The stock price drops below $40 The share price is now lower than the strike price, so your buyer exercises their right to sell you the 100 shares at $40 per share, or $4,000 total. You have the profit of $100 from your premium and that’s not going to cover it, but you’ve still taken a loss. If you actually like $KALE and think its price will rise, you might not mind holding the stock for a while. But if you don’t, then you sell your shares at the market price and lose the difference. With naked put options, losses can be massive depending on just how much the share price falls.

You can access put options within a basic trading platform or online broker. You can buy options in lots of account types, both non-registered, including a margin account and registered accounts, like Registered Retirement Savings Plans, Tax-Free Savings Accounts, and First Home Savings Accounts.

Because options trading is considered to be a bit riskier (more on that next) than many other types of investing, some brokerages require an application before you can get started. Depending on the platform, you may need to meet certain requirements around liquidity (your available cash), trading experience, and trading objectives.

Once you’re ready to buy or sell put options, you can choose the parameters of the put option, including:

Strike price

Expiration date

Number of contracts (the quantity of put options available to buy or sell; each contract represents a standardized number of shares of the stock)

From there, you’ll watch the price of the stock and try to time your move so you can maximize your profits.

Options trading can offer big gains — and big losses. There's no guarantee of returns.

As we covered above, when you’re buying a put option, the downside is limited: you only stand to lose what you paid in premiums.

But if you are selling a put option, and the stock price falls below the strike price in your contract, you’ll have to purchase 100 shares of the stock at the strike price, whatever it is. The further the stock price drops below the strike price, the more money you lose.

Wealthsimple’s Learn pages are meant to be educational. Every story is sourced from and vetted by subject matter experts, and produced by journalists with decades of media experience — people whose primary goal is to teach you something, rather than sell you something. While there may be links included in the article about products that are offered by Wealthsimple Investments Inc. (“Wealthsimple”) or one of its affiliates, these articles are not investment advice, a recommendation to buy or sell assets or securities, or any other kind of professional advice. If you are interested in learning about how Wealthsimple products or features work, please visit the Help Centre. If you are interested in knowing which products are offered by Wealthsimple and which are offered by affiliates, we’ve got a page to help you with that, too.