Money & the World

Why Do We Think Stock Markets Will Go Up Over Time, Anyway?

Maybe it's time to talk about how markets work, and why we think they're the best way to invest for the long-term. We promise: it's super simple and will make you 17 percent smarter about money.

Wealthsimple makes powerful financial tools to help you grow and manage your money. Learn more

Sometimes we forget to ask (and in our case, answer) the big questions. Here's a good one that underpins the entire enterprise of investing: why should I assume I'm going to make money by investing in the stock market?

The truth is that most people — most investors probably — don't actually understand the answer to that question. But we think it's important because the answer isn't very complicated. And because knowing it will make you a better investor with a better chance of building wealth.

And before we get started, we'll even give you a hint: if you think doing well in the stock market is about picking stocks, then you're probably wrong.

Part One: Smart Risks Usually Pay Off in the Long Run

Spoiler alert: the reason you make money over the long-term in financial markets is actually the same reason you sometimes lose money in the short term. How is that possible? We're going to do some light econ here. It will be fun. We promise!

Let's start here: we live in a capitalist society. And for a capitalist economy to work, people need to be able to borrow money. If people can't borrow money, then we're pretty screwed — just look what happened in 2008 when it suddenly got much harder to borrow. But people (and financial institutions) don't necessarily want to lend their money — because there's risk involved.

The answer to that problem is to pay people for taking risks. If you want to spend money you don't have, you have to make it worth someone's while to give you their cash. In exchange for taking the risk you'll never see the money again, you'll get a premium.

That's what's called a risk premium — compensation for the chance you’re taking, and it means that you get more back than you put in, on average. Plus saying risk premium makes you sound smart — throw it around at parties and people will think you know a lot (but also that you are boring).

Anyway, that's how financial assets work. You give money up front, and you get a claim on money in the future that is subject to some risk of loss. An equity (which is another word for a stock) is a good example: You buy an ownership stake in a company that will probably produce profits — and produce a return. Investing in the stock market is risky. So companies have to make it worth your while, on average, to do it.

Sign up for our weekly non-boring newsletter about money, markets, and more.

By providing your email, you are consenting to receive communications from Wealthsimple Media Inc. Visit our Privacy Policy for more info, or contact us at privacy@wealthsimple.com or 80 Spadina Ave., Toronto, ON.

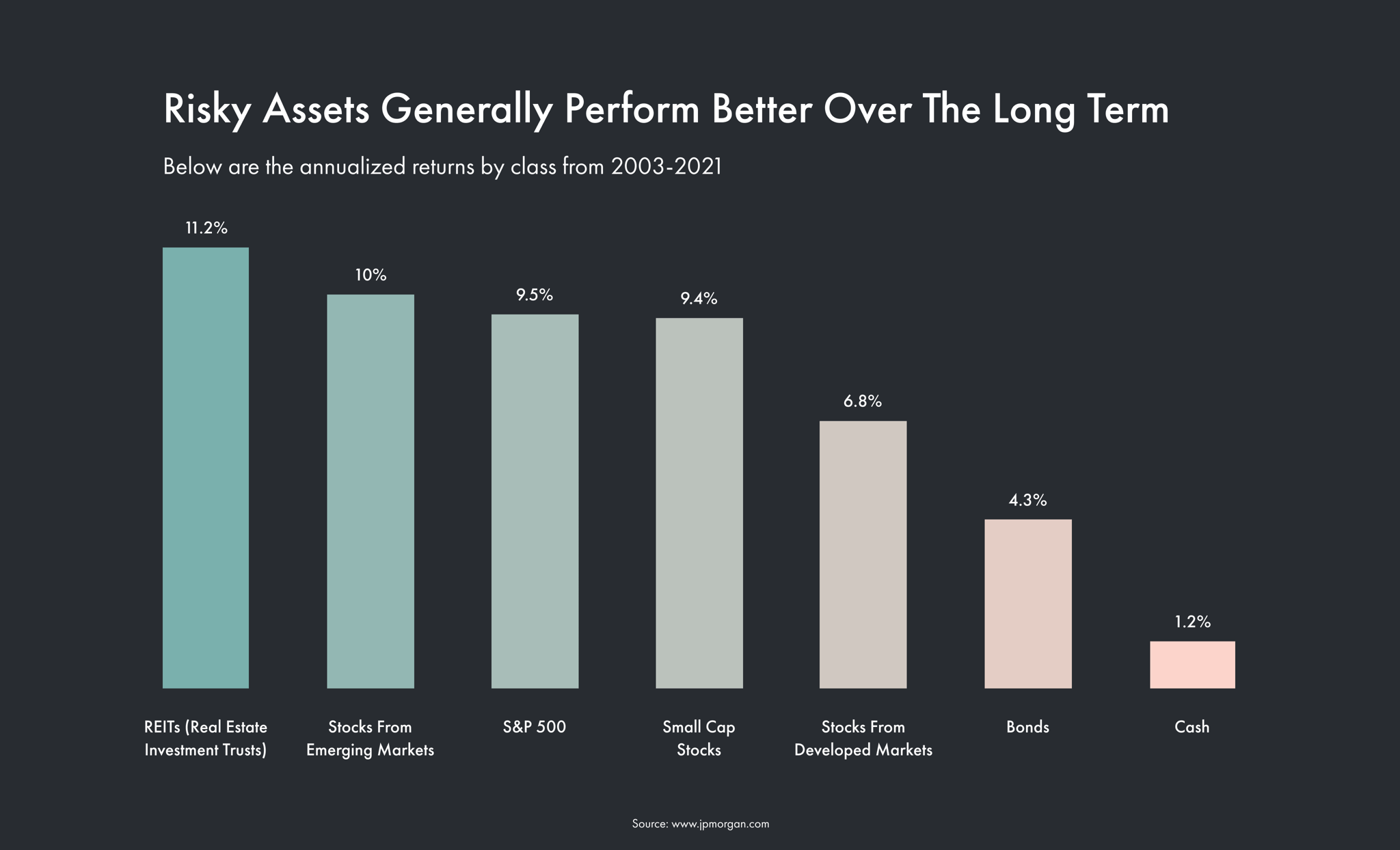

And, as you can see, it's often a pretty good bet:

(Source: LINK)

Part Two: The Government Will Often Step In

Another factor to consider is that the government really wants capitalism to work. They can't control the financial markets — or it wouldn't be capitalism — but they do have some tools to use. For instance, when the economy is too hot, the government will increase interest rates to cool down spending and hopefully reduce inflation (you're probably familiar with this if you've read, well, any news lately.) On the flip side, when the economy struggles and people don’t want to invest, the government will typically decrease interest rates to create economic activity. This makes keeping your money in things like savings accounts a lot less attractive. When interest rates go down, the returns on savings accounts almost always go down. That encourages people to buy riskier assets. Reducing interest rates also reduces how much debt costs — you probably understand this if you have credit card debt and you see your bill goes down when your interest rate goes down. Paying less on debt means people have more to spend and borrow, which stimulates the economy. It's a cycle.

The important thing to remember is the government makes a great effort to make sure riskier investments perform better than cash, and reward people for investing.

And even when that doesn’t work, governments can do a variety of other more extreme things to stimulate the economy. The important thing to remember is the government makes a great effort to make sure riskier investments perform better than cash in the long run, and reward people for investing. It doesn't always work because there are factors outside of their control. But they're powerful tools. Of course, none of that means investors don't sometimes lose money. Investors lose money all the time. Here's why.

Part Three: What Negative Returns Mean

Sometimes markets go down and if you're invested in those markets, you lose value. We're not talking about one company tanking, which can happen for lots of reasons. We're talking about the performance of entire markets. Why do they go down? There are two big reasons.

1. Investors need cash more than they want risky assets.

All assets lose money when a large enough group of investors decide that holding cash is better than investing in risky assets. That causes the price of all those risky assets to decline. Why do people suddenly decide it's better to cash out? It might be because people become more fearful about the future, often in response to some bad news. Or because they need to sell their riskier assets to pay their debts. Maybe servicing debt has gotten more expensive, or borrowing money has gotten more difficult, because banks are nervous.

(We'll get to the second reason later.)

Recommended for you

Part Four: How do I know markets are highly likely to go back up after a downturn?

Sell-offs, downturns, crashes. They happen all the time. But they don't tend to last forever. Why? Well, it's not just because we've gotten lucky. Remember, there are social and economic underpinnings at work behind financial markets. First of all, the government takes action. Throughout history, when markets have been in serious trouble (think the Great Depression or the 2008 recession) central banks and governments have pursued extraordinary measures to restore them. How do they do that?

Usually they have devalued cash to generate inflation and to stimulate the economy. During the Great Depression, the US government reduced the cash interest rate to zero and devalued gold. This reduced the attractiveness of cash as an asset. After the 2008 financial crisis, the Federal Reserve reduced the short-term interest rate to zero and then bought a lot of available low-risk assets (this was called quantitative easing) when they needed even more stimulus. This forced investors to take more risk if they wanted return.

This is one of the reasons cash isn't a very good investment over the long term — and, if you're not planning to spend your money soon, can be said to actually be riskier than investing in equities. The government will devalue cash when it suits its interests to do so, and meanwhile, you've given up your risk premium.

Part Five: Didn't you say there were two reasons markets go down sometimes?

Yes. And let's talk about the second reason: The scourge of uncertainty.

Individual assets or groups of assets can also lose money when what transpires is different than what investors expect to happen. If investors think all the big tech firms in America are going to grow like gangbusters and then we look at the financial pages and there's a news alert they did not grow like gangbusters, well, equities in that whole sector are likely to decline in value.

If you are betting on something happening, you will lose money when the reality of the world doesn't match your expectations.

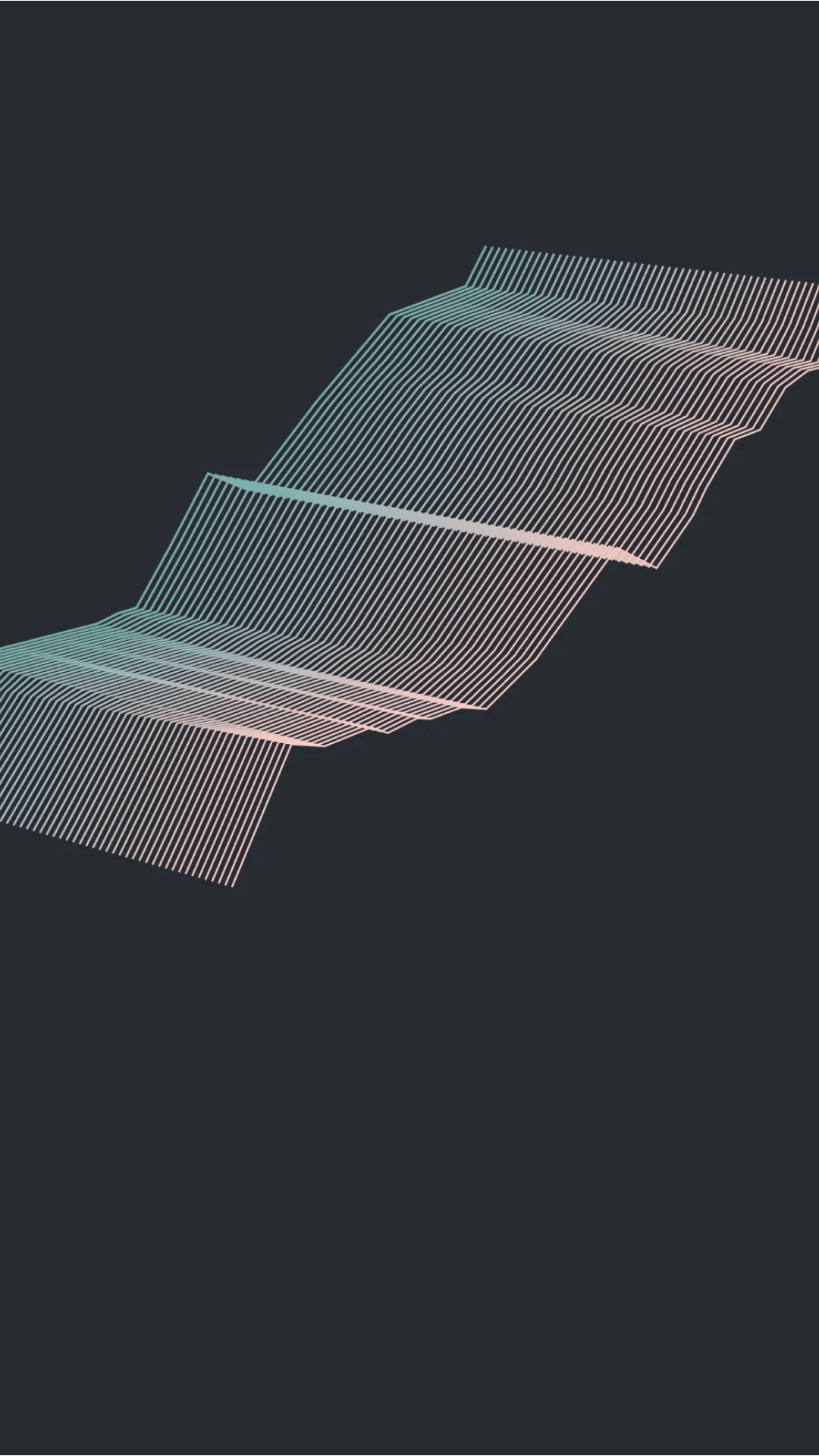

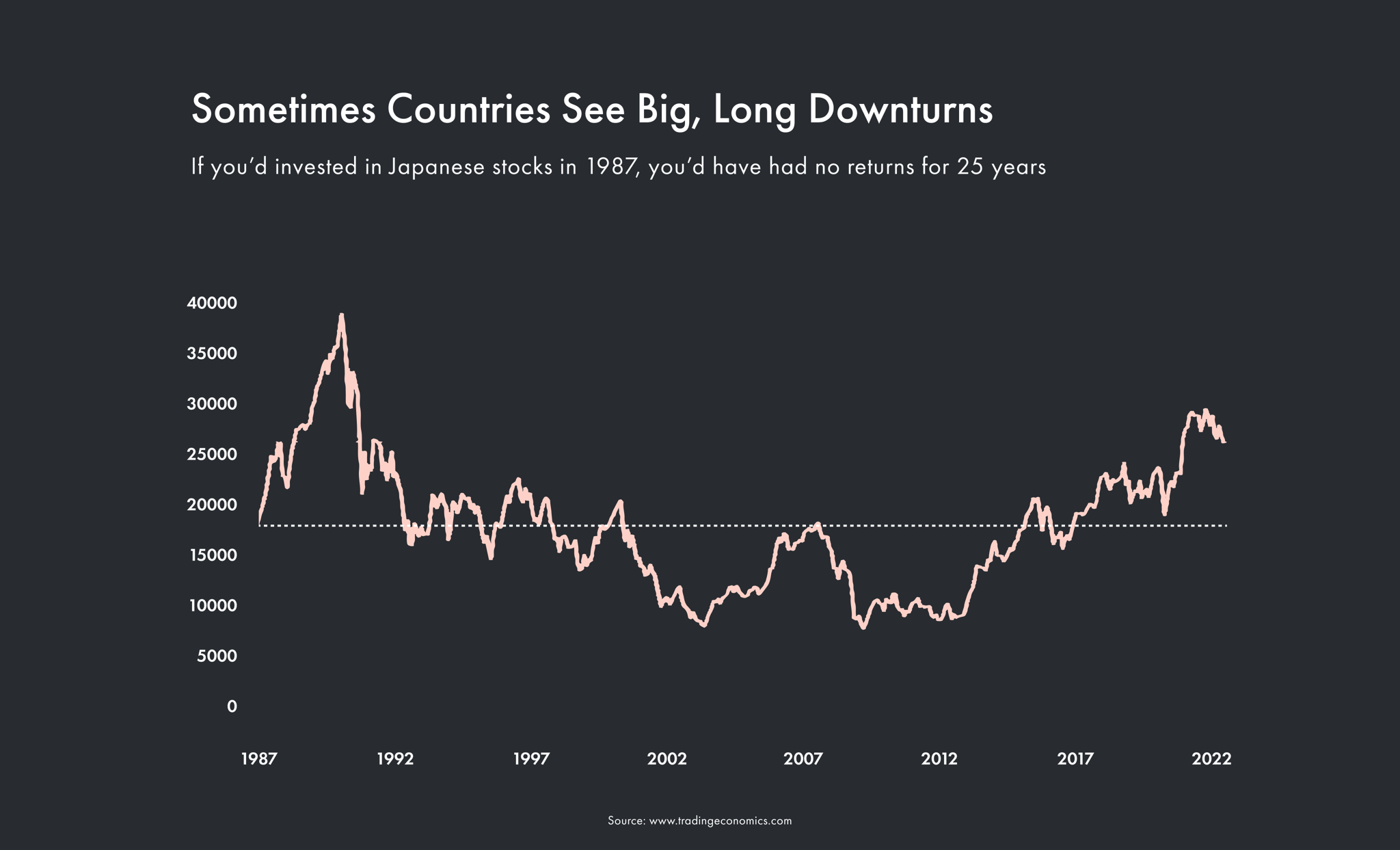

And the truth is that bad news can persist for long periods of time, even for an entire country. Consider the case of Japan in the 1980s. Conventional wisdom back then said Japan was about to become the world's largest economy because of its manufacturing prowess. Instead, the Japanese economy entered a period of extremely slow economic growth. If you had invested in Japanese equities in 1987 as they were entering an asset bubble, you wouldn't have realized a profit for the next 27 years.

Here's a graph that shows how an investor who'd bought Japanese equities 1987 would have had no returns for 25 years.

(Source: LINK)

If you have all your eggs in one basket — even if that basket is a whole country — bad news can hurt you for long periods of time. If you are diversified — across sectors, across countries, etc. — you reduce the chance that even extremely rare bad news (like Japan getting hit with a 30-year deflationary depression) will prevent you from realizing your goals. Which brings us to our next point.

Part Six: How do I make the risks of investing less risky?

Historically, your investment will be less risky if you avoid investing in just one sector or one country. You've got to be more strategic.

As an investor, you should be dispassionate. Unemotional. Strategic. And you shouldn't assume that, just because something happened in the past — even if it happened a lot in the past — that it'll happen again in the future, or even the present. For example, equities in the United States have outperformed equities in the rest of the world for the last century, which reflects the fact that the American economy consistently did better than it was expected to.

No one can prevent losses. But what you can do is diversify your holdings enough so that any loss in an individual asset will have little effect on the entirety of your portfolio.

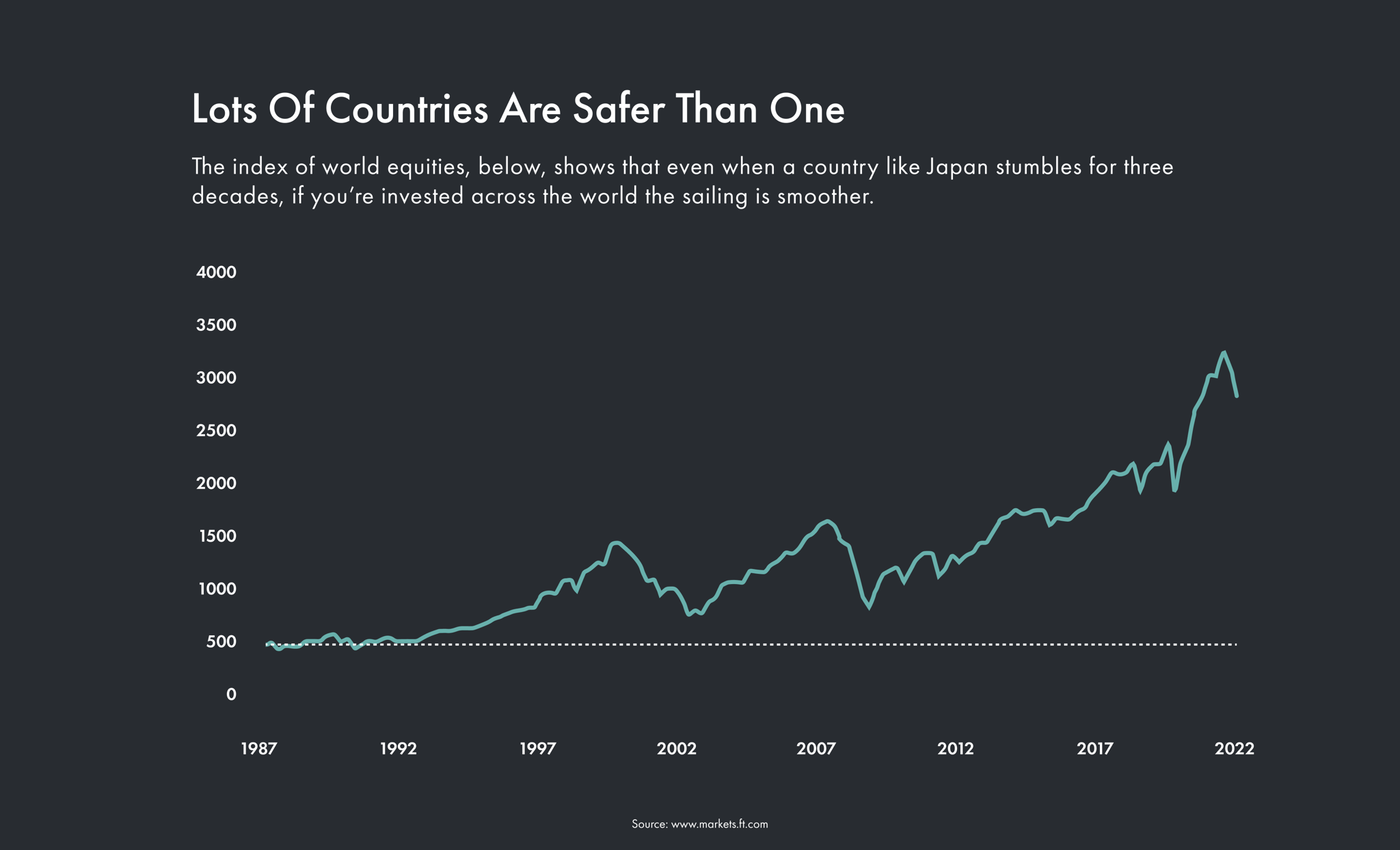

But we're not sure that will continue to be the case — just as we're not sure that it won't. What we're more confident in is the more broad concept that risky assets, like equities, will continue to outperform cash over time. That's why we think it's smart to bet on the performance of these types of assets in general, not on these type of assets in any one sector or country. So the smart bet is to invest in a globally diversified portfolio.

Check out the graph below that shows what your returns would be if you invested $10,000 in equities spread around the world. And compare that to what the investment would look like if you'd only invested in Japanese equities.

(Source: LINK)

No one can prevent losses. But what you can do is diversify your holdings enough (not to mention keep them balanced as the market fluctuates, something Wealthsimple Invest does automatically) so that any loss in an individual asset will have little effect on the entirety of your portfolio.

The only other ingredient is time. Keep your money in long enough and that graph tends to go up and to the right.

This story was originally published in November 2018 and updated in April 2021.

Wealthsimple's education team is made up of writers and financial experts dedicated to making the world of finance easy to understand and not-at-all boring to read.

The content on this site is produced by Wealthsimple Media Inc. and is for informational purposes only. The content is not intended to be investment advice or any other kind of professional advice. Before taking any action based on this content you should consult a professional. We do not endorse any third parties referenced on this site. When you invest, your money is at risk and it is possible that you may lose some or all of your investment. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Historical returns, hypothetical returns, expected returns and images included in this content are for illustrative purposes only.