Finance for Humans

RRSP vs TFSA: What’s the Better Choice?

In this battle of the tax-sheltered accounts (and who doesn’t love to see a good fight between tax shelters?), we tell you when you should put your money in an RRSP, when you should pick a TFSA, and when you should do both (if you can!).

Wealthsimple makes powerful financial tools to help you grow and manage your money. Learn more

Life is good at putting humans at crossroads and forcing them to make tough decisions. Like: should I stream this one show that starts great but doesn’t pay off, or this other show that starts great but doesn’t pay off? And which of these investment accounts should I be using given my particular age and tax situation? You know, fun “would you rather” bar conversations. As far as that second question goes, if you’re wondering if you should be contributing to an RRSP or a TFSA this year, we can definitely help with that. (Not to complicate things, but if you’re considering buying your first home, an FHSA can also be worth adding to the mix. We’ve got an article — and a flowchart! — to help you with that decision, too.)

What the heck is an RRSP?

RRSPs, or Registered Retirement Savings Plans, have been around for a long, long time. Created in 1957 as motivation for Canadians to save for retirement, RRSPs are accounts that allow taxpayers to shelter part of their pre-tax income to help fund their retirement. The money in an RRSP account can be invested at the discretion of the account holder and will only be taxed when it’s withdrawn. Every year, Canadians are allowed to contribute as much as 18% of their income from the previous year into an RRSP — although there is a limit, which the government sets each year. (In 2024 the limit is $31,560.) Here’s a hypothetical to help you understand. Say you earn $75,000 a year and you want to contribute the maximum 18%, or $13,500, to your RRSP. You’ll only pay tax on $61,500 of your income this year. Meanwhile, that $13,500 in your RRSP will hopefully be earning healthy returns. You’ll pay tax only on the $13,500 (and any gains) later, when you withdraw it in retirement, after your investment has, fingers-crossed, grown a lot.

There are a bunch of reasons RRSPs are awesome (or as awesome as tax-advantaged retirement accounts get). Here are a few:

Sign up for our weekly non-boring newsletter about money, markets, and more.

By providing your email, you are consenting to receive communications from Wealthsimple Media Inc. Visit our Privacy Policy for more info, or contact us at privacy@wealthsimple.com or 80 Spadina Ave., Toronto, ON.

Matching funds: Many employers offer group RRSPs to their employees, and they’ll usually match your contributions up to a certain percentage. If an employer offers a 5% match, it generally means that if you contribute $2,500 (5% of a $50,000 salary), they will do the same, bringing your total investment to $5,000. “No matter what, you should do your best to take advantage of this,” says Zoe Wolpert, Senior Investment & Retirement Specialist at Wealthsimple. “Otherwise, it’s like turning down part of your salary.”

Potentially lower taxes in retirement: As we mentioned, RRSP contributions lower your taxable income. The money in an RRSP grows tax-free, and you are only taxed when you withdraw. For most of us, our incomes will be lower in retirement, which means our tax rate will be too. Also, keep in mind that you won’t be withdrawing all your money at once (which would likely mean a pretty high tax bill). Instead, the year you turn 71 you’ll be required to convert your RRSP to an RRIF, or a Registered Retirement Income Fund. Every year after that, you’ll have to withdraw a mandated minimum percentage, and you’ll pay taxes on that money. But all the money that stays in the RRIF continues to grow.

Then what in tarnation is a TFSA?

TFSAs are another type of tax-advantaged savings account that offer a lot more flexibility for tax-free saving than RRSPs. Created to give Canadians an incentive to save money, TFSAs have been around only since 2009. Though TFSA is an acronym for Tax-Free Savings Account, it’s a bit of a misnomer, since they’re not like garden-variety savings accounts at all. As with RRSPs, funds in TFSAs can be invested in countless ways. And like RRSPs, TFSAs have contribution limits that vary year-to-year, and any unused room carries over to the following year. (In 2024, the annual limit is $7,000.) And that contribution room accumulates. So, for example, anyone who was 18 or older in 2009 would have room for a total of $95,000 in their account in 2024. (So long as you turned 18 before 2009, you can calculate your total contribution room using this chart.)

Here’s the big difference, though: the money you contribute to a TFSA is after-tax income. This means that money, and any investment growth it earns, won’t be subject to any further income tax. So: no taxes when you take it out.

Recommended for you

Did You Lose Money Trading Stocks? Blame Your Caveman Brain

Finance for Humans

Ask Lizzie: Is it OK if I Use Shopping to Make Me Feel, You Know, Happier?

Finance for Humans

You May (Still) Have to Pay Taxes on COVID-19 Benefits

Finance for Humans

The Bond Market Fell, Hard. An Explainer for Normal Humans

Finance for Humans

Let’s revisit our example: if you earn $75,000 this year and deposit $20,000 into a TFSA (instead of an RRSP), you’ll still be taxed on $75,000 of your income this year. But when you withdraw money from your TFSA, you won’t pay one additional penny of tax on your initial $20,000 investment or any of the gains you made on that money over the years.

Here’s a list of one (1!) giant advantage to TFSAs:

Access to your money: TFSAs are the Olympic gymnasts of investment accounts. They really couldn’t be much more flexible. Saving for a big vacation or a sabbatical? Grab $20,000 from your TFSA. If you want that room back, reinvest as soon as the following year or whenever you darned well please — even 10 or 20 years from now. As long as you’re alive, that TFSA room is yours. And it doesn’t even matter if that $20,000 began as a $10,000 investment that flourished in your account; you still get that $20,000 of room. If you don’t have to, don’t choose one account type over the other! If you’re lucky enough to have the means, it’s actually a stellar idea to max out your contributions to both an RRSP and a TFSA. Why not get the most out of tax-advantaged accounts before stuffing money into accounts that aren’t tax-advantaged? Otherwise, you’re effectively turning down free government money. Of course, a lot of us won’t have the ability to do that. So we’ll have to prioritize.

Why most of us should pick an RRSP over a TFSA

In most cases, if your employer offers a group RRSP with matching funds, the first thing you should do is invest the maximum amount that your employer will match before turning to your TFSA. “The absolute first place you should start investing is in your work matching program if you have one,” says Wolpert.

Taxes shouldn’t be taxing.

From our sponsor

Taxes shouldn’t be taxing.

Wealthsimple can handle simple tax returns or complex ones — even as complex as yours. And it only costs whatever you’re willing to pay.

Also important: if you earn more than $53,359 (2023's lowest federal income tax bracket) or $55,867 (2024's lowest federal income tax bracket) a year, you should always contribute to your RRSP first. The goal is to bring your income down to a lower tax bracket. "If you’re making less than the lowest tax bracket, you’re already there and don’t need the help of an RRSP contribution. But if you aren’t, contributing pre-tax can bring your rate down.

There is one thing to consider when it comes to RRSPs: whether you might need your money before you retire. The big knock on RRSPs (and, come to think of, pretty much the only knock) is that they’re not especially forgiving if you withdraw from them before retirement. Though the money in an RRSP is yours and available for withdrawal at your whim, if you take some out, it will be considered taxable income and you’ll owe (or have withheld) income tax on the amount you withdrew. And, unlike with a TFSA, you won’t get contribution room back; once you’ve withdrawn from an RRSP, poof — that contribution room is gone for good. There are only two exceptions to this: the government’s Home Buyers’ Plan (HBP) allows first-time homebuyers to borrow as much as $35,000 from their RRSP to buy their first house; the money needs to start being paid back two years after it’s withdrawn and fully paid back over the next 15 years. Similarly, the Lifelong Learning Plan (LLP) allows for up to $20,000 in RRSP withdrawals to be spent on higher education and, like an interest-free loan, can be replaced over 10 years with no cost to you. Any required amount of either HBP or LLP not paid back in a given year will be included as income that year.

When you should pick a TFSA over an RRSP

If your employer doesn’t offer a group RRSP and you earn less than $55,867 a year, you should probably contribute to your TFSA first. As discussed above, the higher your income is, the more it’s taxed. If you fall below that magic $55, 867 level, though, you’re in a low tax bracket already. That means you don’t need the immediate tax benefit that would come from RRSP contributions.

One thing to be aware of: TFSAs may not be ideal for savings. In some ways, having “savings account” be part of the name of a TFSA is a really lousy idea. TFSAs are an excellent tool to avoid paying taxes on investment gains; they are not, however, optimally used like a savings account — a stable, low- or no-risk place to park funds that you will need to access in the immediate future. Because you only have a finite amount of room in a TFSA, it’s best to use it to invest in a manner that might actually earn a considerable return, like stock investments. “Ideally, you don’t want to put the lowest-growth parts of your financial situation in the TFSA,” says Wolpert. “If you’re using up your room, you really want to use the TFSA for things that are going to make you money over time so that you don’t have to pay tax on that.”

Still not sure?

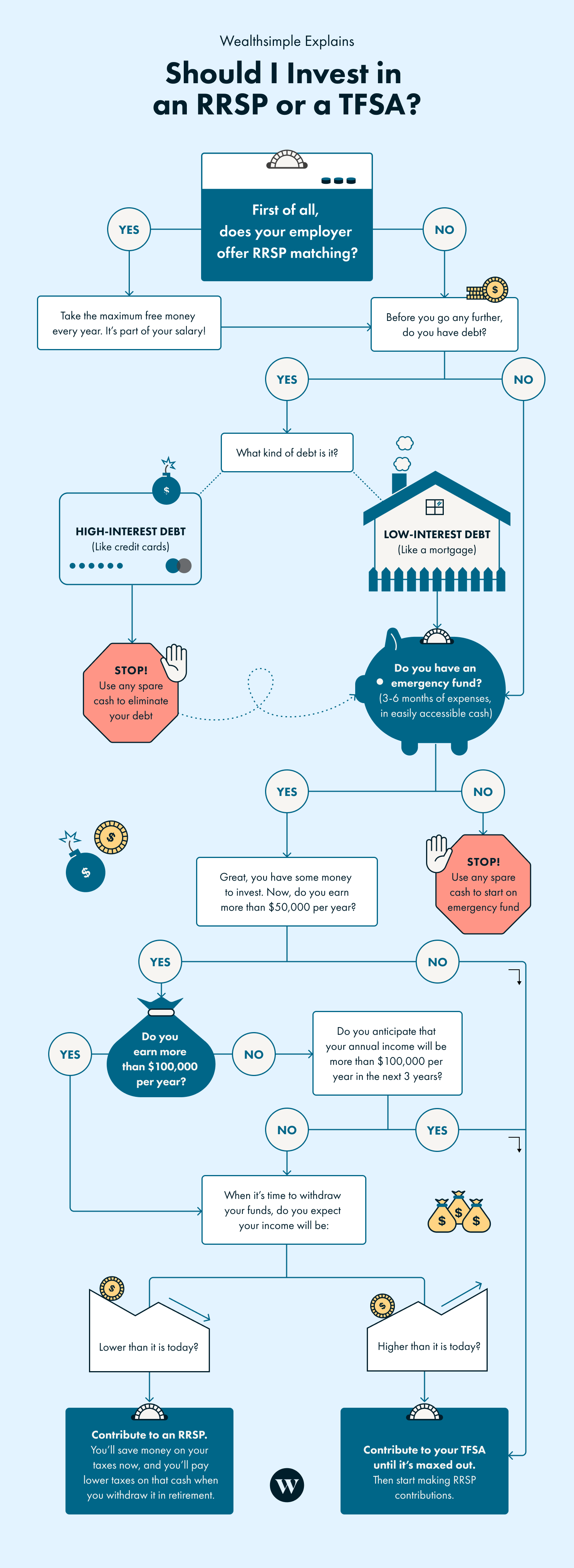

While we don’t actually have the fun coin toss game you see up top, we have the next best thing for you. Choose your own “tax-sheltered account” adventure with this handy flow chart:

Andrew Goldman has been writing for over 20 years and investing for the past 10 years. He currently hosts ["The Originals"](https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/the-originals/id1439490906 ""The Originals"") podcast and writes about personal finance and investing for Wealthsimple. Andrew's past work has been published in The New York Times Magazine, Bloomberg Businessweek, New York Magazine and Wired. He and his wife Robin live in Westport, Connecticut with their two boys and a Bedlington terrier.