Finance for Humans

Ask Lizzie: I Want to Give Money to What’s Important, But I’m Worried About My Financial Future

Our columnist on balancing a real fear for your future with a real desire to do good for others.

Wealthsimple makes powerful financial tools to help you grow and manage your money. Learn more

Dear Lizzie,

The last few months have been — duh — completely insane. For the longest time there’s been a mysterious irritant that’s been troubling me at the back of my mind, and I just now realized what it is. I’m 38 years old, and the world has never felt more uncertain in my life. At the same time, I can’t think of another time in my life when people are more in need than they are right now. So how do I balance that? How do I balance my worry and need to take care of myself and family with the need to help, give, and be generous?

To make it more concrete, what’s more important, maintaining my emergency fund in case I get laid off or contributing money to the people and organizations that need help?

Pandemically Puzzled

Dear Puzzled,

Thank you for giving me the chance to answer a question that consists of equal parts personal finance, macroeconomics, and moral philosophy. My favourite pie chart. If you have studied philosophy, or (more likely?) watched any of the NBC show The Good Place, you may have come across a phrase from ethicist T.M. Scanlon: It’s the title of his best-known book and also an episode of the show.

His book focuses, among other things, on the social contract and “our obligations to other people, which I think is what you’re asking about. I’m certainly not a Scanlon scholar, so I will let him speak for himself: “The idea is that actions are wrong if a principle that permitted that action couldn’t be justified to the affected people in the right way.” In the harshest phrasing: can you justify your emergency fund to someone who is literally starving?

Hey, I warned you it was a harsh question! But let’s back up and unpack this concept a little.

What we owe to each other depends in part on relationships. And it’s a complex moral question.

First, a note of compassion. These questions are hard. And there’s no perfect answer in this situation. And even being able to ask these questions means you are in a position of privilege. And that’s OK! It’s also pretty great that you’re taking the time to wrestle with it instead of reflexively just hoarding as much as possible.

Now to the finances. In my view, what we owe to each other depends in part on relationships. And it’s a complex moral question. Some of us construct our lives on the idea that we owe the most to the people closest to us; others on the idea that we owe the most to those who have the least. I suspect the majority of people (or at least those who write in with a question like this) are somewhere in the middle. To take an example from my own life, I owe it to my dependents (like Sam, my son, who was born two weeks ago!) to make sure that I care for myself, and by extension, them. While I was pregnant I thought a lot about how I wouldn’t be holding up my end of the mutual care bargain if I treated my body like junk, even if I really wanted to lie on the couch, eat Cheez-Its and watch British crime procedurals 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, for 9 months. So as part of my social contract with my unborn baby, I only lay on the couch eating Cheez-Its for a few hours a day. Sacrifice!

For most of us, caring for ourselves and our family are our first obligations. Especially now. The International Monetary Fund recently revised its gross domestic product forecast downward for the year, so there’s that. And the U.S. is now in an official recession. Pretty much every major economic forecaster says we are going to be in a period of contraction around the world, and both the duration and path out of it are uncertain. In a situation where the macroeconomics are tenuous, there is a starker moral imperative to make sure that the people depending on you have what they need. But! What they need may not be exactly what they want (apologies, Mick Jagger). So, yes, I don’t think it’s selfish to be sure that your basic expenses are covered. And that you’re paying attention to your financial health — if you have any high-interest debt, you’re trying to make a dent in it, and that you have some money saved in an emergency fund to take care of the people who depend on you, in case things get worse. Most personal finance experts recommend saving up to six months worth of expenses.

Recommended for you

Ask Lizzie: Is it OK if I Use Shopping to Make Me Feel, You Know, Happier?

Finance for Humans

The Budget for People Who Hate Budgeting (and Also Want a Bidet)

Finance for Humans

10 Books That’ll Teach You Everything (Or at Least a Lot) About Money

Finance for Humans

Nervous About Overheated Stocks? Let’s Revisit Four of Our Best-Ever Insights

Finance for Humans

This doesn’t have anything to do with your question, but I would be remiss not to indulge the financial planner part of my brain and say: I know that saving can seem really daunting if you’re just trying to get started. Two easy tips: one, open a high-yield savings account. Even though interest rates around the world are quite low right now, that will give you a little boost. And two, see if you can automate a piece of your paycheck to go straight to savings, before you even look at it. It can be really small. That’s OK! You have to start somewhere.

But even as it’s a time to be cautious, it’s also a time to be recklessly generous if you can. Which brings me to the social contract. I don’t think you would have asked about your desire — even obligation — to give if it weren’t important to you and how you see the world. For some people it isn’t. I’ve come across folks in this lockdown who have the ability to pay, say, a housecleaner who isn’t currently working, and choose not to. They felt that their sole obligation was to their families. But I don’t think that’s you.

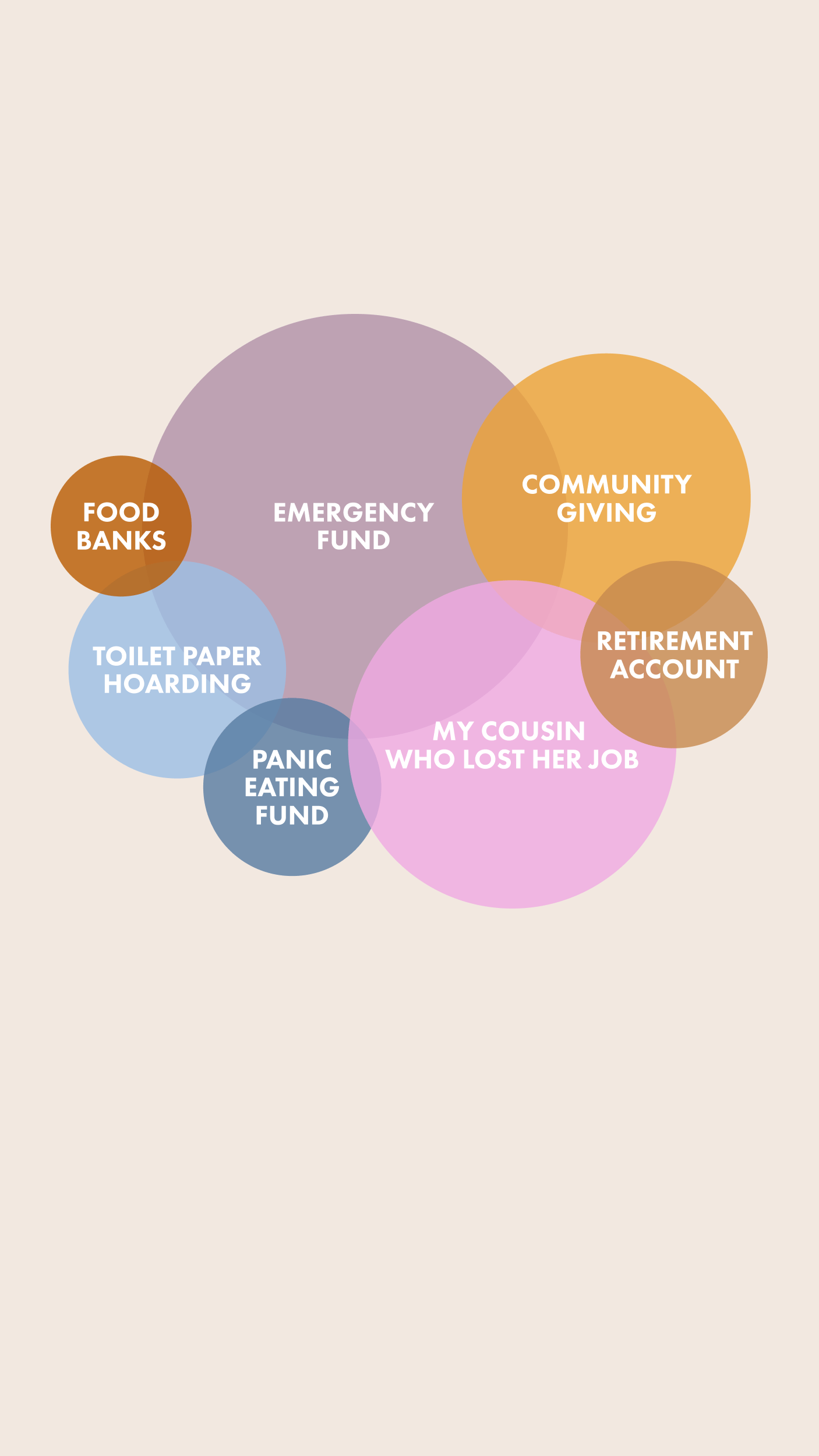

But when you’re trying to figure out what to do with that obligation, it helps if you have a framework to think about generosity. I’m going to break down a couple ways to do that. One is to visualize concentric circles. The innermost circle is what we’ve already covered: the people who literally depend on you. Then, there is a circle of people who provide the services that you would pay for in what we now refer to as Normal Times. Maybe that’s cleaning, or child care, or someone who helps with pets. Since I currently have the financial ability, I have chosen to continue paying those people. I may not be able to pay the full amount I normally do, but I pay what I can. It helps them stay afloat, and I think it’s the right thing to do.

In this model, one more circle out could be people you might not normally pay, but who could use it right now. Perhaps these are friends, family members, or acquaintances who have lost their jobs. I have about four people in my life right now to whom I regularly kick grocery money. I can’t afford to cover their rent, but I can help them with $25 here or there to take the sting out of some bills. Early on in the pandemic, I asked a few people who I knew were being furloughed or losing their jobs, if a little extra money for, say, groceries, would help. They said yes. Since then, I’ve just continued doing it — a little Venmo here and there. It’s my admittedly small version of what I owe to these people. I want them to come out the other side of this thing as intact as possible. And since I can do it, I do.

Do you have a burning money etiquette question?

ASK LIZZIE

Do you have a burning money etiquette question?

Ask our expert columnist, Lizzie O'Leary, and she may answer you in an upcoming column.

Of course, this means you have to talk about money with people, and they’re going to have to be honest with you about it. That’s good. One of the hardest things about money is how rarely we talk about it. We feel shame because we don’t come from money, or shame because we do. Shame because we can’t meet all our debts. Or because we’re “bad” at managing money. In my experience writing about finance, the more we discuss money, the more we can quash that shame. Money itself has no moral value. Reminding ourselves of that is important.

Our next circle in this model is comprised of people who you may not know personally, but worry about. Is it the workers at a particular neighbourhood business? Is it aides at a nursing home near you? There are certainly plenty of food banks that could use your help. And there are also old-fashioned mutual aid societies, where neighbours pitch in to help other neighbours. I think often we tend to worry that if we can’t afford a large donation, our help isn’t needed. Nonsense. Small amounts of money, or in-kind services are important. Can you do the shopping for someone who is older or immunocompromised? That’s wildly valuable. Or perhaps volunteer to drive groceries to people — many houses of worship are organizing such efforts.

The second framework for thinking about giving is about who needs the money most, and who is best at putting money to work. Because you may not personally know the people who need help the most; the causes that are most important to you — like racial justice or kids who normally get free lunch at public school — may not be addressable in your concentric circles. If you want to think about generosity from that model, it can be helpful to look at Charity Navigator or Guidestar. They both rate nonprofits and can tell you if an organization spends a disproportionate amount on stuff other than helping folks — like marketing or overhead. Some of the places I mentioned above are great, too. Food banks, charities, and many religious institutions are efficient at stretching a dollar because they have a lot of practice doing it. Food banks, for example, often buy in bulk and can get discounts that an individual can’t. Even with smaller groups, it can be helpful to ask how long they have been doing community or volunteer work. Experience counts. And as I said earlier, many places will accept donations of time and effort! You do not have to be strictly laying out money to make a difference.

But I want to return to the idea of “what we owe to each other.” I think the basic answer is: it really depends on what kind of world we want to live in. And what I hear in your question is that you want a world where we look out for one another. Where we find connection even in the hardest of times. And where you will know, 20 years from now, that you did your best to care for other people.

Lizzie O'Leary is a longtime economic and policy journalist. She hosts the podcast “What Next: TBD” at Slate.