Money Diaries

What I Learned About Money Growing Up on a Commune

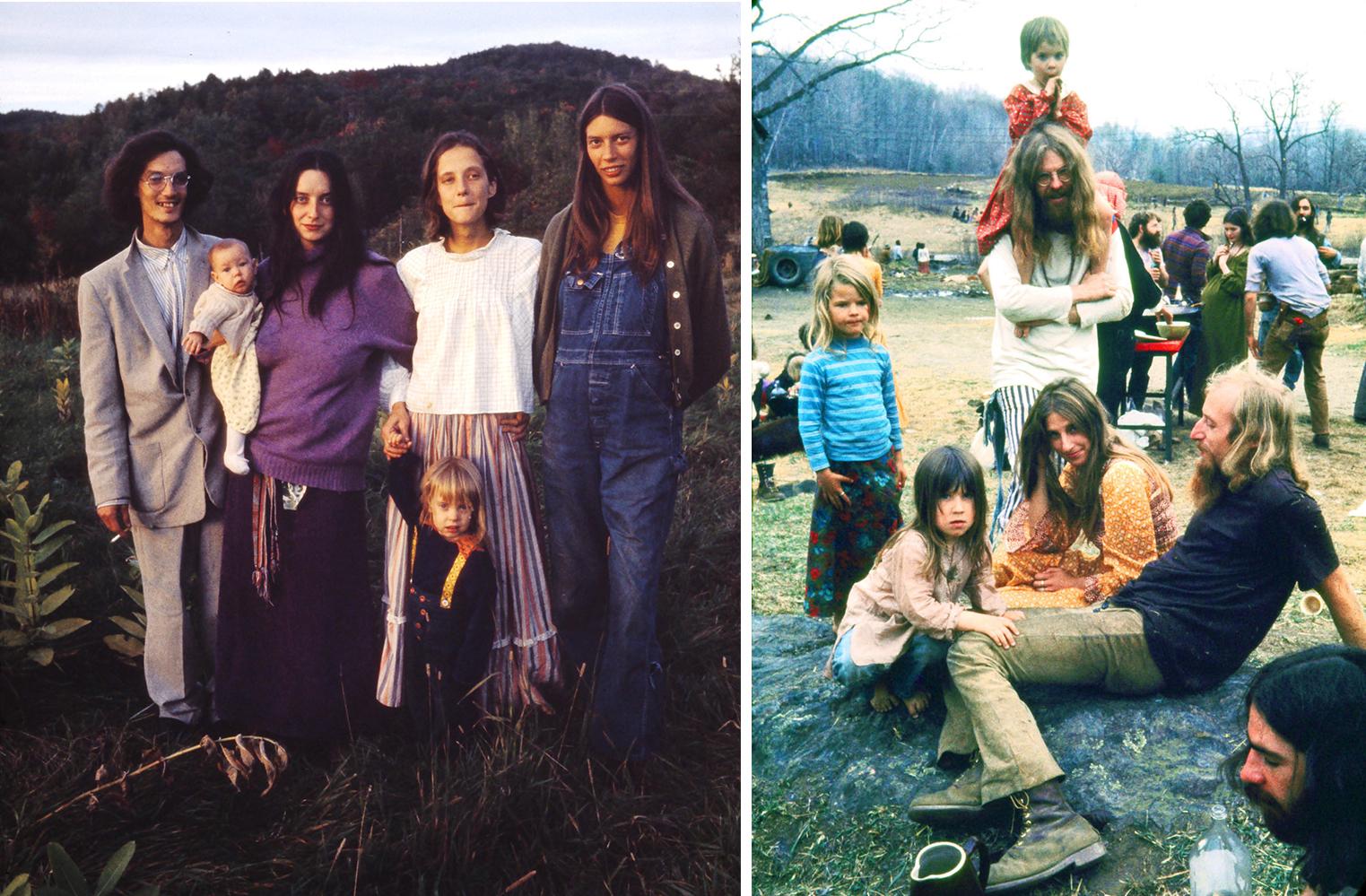

The author grew up on one of the most famous communes to arise from the 1960s. It shaped her, but that doesn’t mean she wanted to go back.

Wealthsimple makes powerful financial tools to help you grow and manage your money. Learn more

Wealthsimple is an investing service that uses technology to put your money to work like the world’s smartest investors. In “Money Diaries,” we feature interesting people telling their financial life stories.

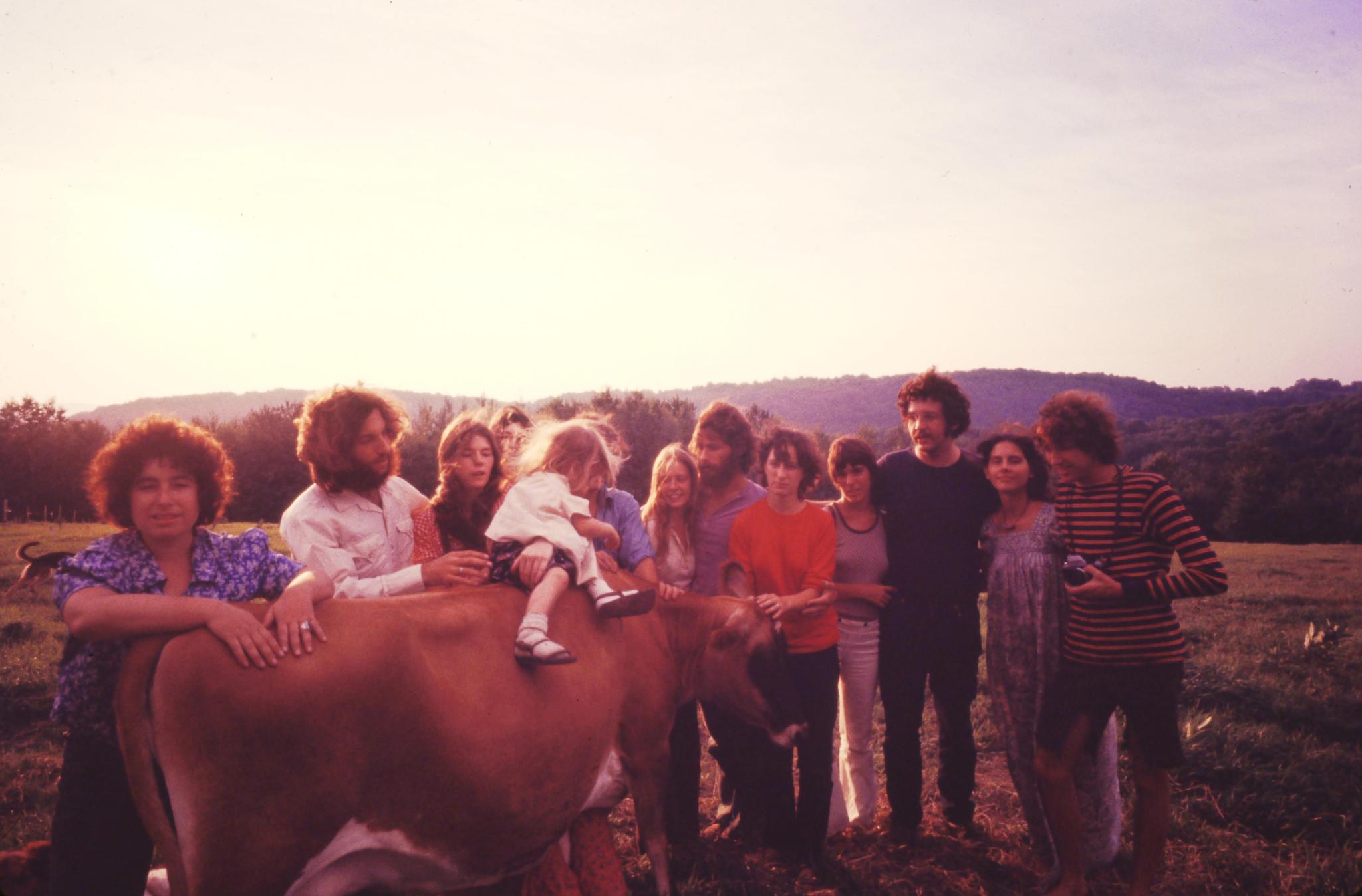

In 1968, my father, Marty, used the money he had received for his bar mitzvah 15 years earlier to put a down payment on an 80-acre farm on a hilltop in Vermont. He split it with a friend, Ray Mungo. My dad and Ray were both active in the anti-war movement in New York City, and they dreamed of starting a commune on the farm, where a group of their friends would come together to make art and build a haven away from America’s conflict-ridden cities. Marty and Ray each committed $2,500. They called their commune Total Loss Farm.

It became one of the longest-lasting communes in the Northeast, and a site of counterculture pilgrimage for artists and activists through the ’80s. Taj Mahal, James Taylor, and Grace Paley all passed through. When I was a teenager, I learned that a former resident, a woman I’d always admired, had been a member of the Weather Underground, and the name I’d always called her was a pseudonym that she’d adopted while living as a fugitive in hiding. Needless to say, the FBI made appearances over the years. There were sex and drugs to be had at the farm, but those weren’t the organizing principles of the place, and maybe that’s why it lasted so long.

In 1968, Ray (who was responsible for spinning the most enduring myths about the farm, in his books Famous Long Ago and Total Loss Farm: A Year in the Life) wrote about the idea behind the institution: living with “no more me, no more you.” Everything was to be shared at Total Loss Farm, and expenses would be paid by whoever could afford to chip in.

The commune was founded on a set of principles — sharing property, living off the land — that my life, and all our lives out here in what we call the real world fundamentally violate.

My parents met at the commune in the late 1970s. At first I spent only summers at Total Loss Farm, but when I was 10, my parents broke up and I lived there full-time for two years with my dad. In some respects, the way of life engineered by my parents there was my birthright. Many of the ideals that continue to underpin my life came from growing up there.

Some communes were founded for the sake of free love, or to honour the environment, or to study Buddhism; Total Loss was built upon the simple importance of a good hang. It was made up mostly of artists and based on the social enterprise of sitting around the kitchen happily bullshitting. To this day, I share the belief that to be able to spend time with your friends at leisure and in peace may be the highest expression of civilization.

But I never really considered living there. I continued to spend summers at the farm until I was 12 years old, when my dad moved off the commune and into town. I went to college, and then I followed my boyfriend to New Orleans, where I became a writer (while waitressing). We got married. We missed a climate with four seasons, so we moved to Canada, where we both have citizenship. I got a job working for a men’s website, and he got a teaching position. We had children.

Meanwhile, 50 years on, the counterculture that the original founding gang was a part of at Total Loss has been completely assimilated by global capitalism. Yoga and organic farming are corporatized. Feminism, anti-racism, gay rights, the importance of eating locally, recycling — they’re now mainstream concerns. People everywhere now like to show up to costume parties dressed as “hippies.”

Last year, the founding members of the commune began to plan its 50th reunion. It has shed its apt name, and is now known as Packer Corners Farm. I visit a few times a year; my mother lives nearby, and Verandah Porche, one of the founding members and a woman as close to me as any of my blood relatives, still lives in Packer Corners’ main house.

Sometimes I wonder what it would have been like had I decided to live my life there; the commune was founded on a set of principles — sharing property, living off the land — that my life, and all our lives out here in what we call the real world fundamentally violate. Growing up there, I understandably had only a child’s view of (what I now know was) a really strange economic undertaking. So in June, my family and I headed back to Packer Corners to help sort out the historical myths from the facts.

—

Visiting Packer Corners now is like passing through a portal to a place where time stands still, like the village of Macondo in One Hundred Years of Solitude. Much of what has always been there remains, either growing uncontrolled or gently rotting: a hillside peach and apple orchard, an outhouse whose cedar shingles are molting off.

Sign up for our weekly non-boring newsletter about money, markets, and more.

By providing your email, you are consenting to receive communications from Wealthsimple Media Inc. Visit our Privacy Policy for more info, or contact us at privacy@wealthsimple.com or 80 Spadina Ave., Toronto, ON.

We had been planning the 50th reunion for a year. More than 100 people came from all over the world to spend the weekend catching up and taking walks around the farm’s hilltop neighbourhood. My family and I stayed in our cabin; we had a cooler of beer on our porch reserved for the “younger generation.” Everyone gathered under a big tent in the front yard for huge potluck meals, poetry readings, an impromptu production of scenes from A Midsummer Night’s Dream (I read the part of Hermia). It was an emotional weekend for many people; not so much for me. At 35 years old, I have my own friends to have nostalgic reunions with — I have no need to get nostalgic on behalf of my parents.

But I got into some interesting conversations. How did sharing really work at the individual level? Those grudges and hurt feelings that I heard all about as a kid while eavesdropping on after-dinner conversations — did those ever fade? Fifty years after Packer Corners’ founding, is it even possible to maintain the lifestyle it was founded on?

One of the founders of the farm, Richard Wizansky, now lives down the road with his husband, Todd. He spent many years acting as treasurer, a role that’s funny to consider (isn’t it anathema to the premise of a commune to have a treasurer?). “Our only financial concern was paying the mortgage each month, which was $272.30,” he told me. “So we had to collectively come up with that, but there was no financial obligation if you lived at the farm. Whoever could chip in, would.”

The whole transaction existed outside the financial system. They paid the mortgage directly to the elderly woman who had sold them the farm; a bank was never involved, interest rates were never discussed. “We’re her major source of income so we can’t miss a payment,” my dad wrote of the commune in one of the books the members collectively published, Home Comfort: Stories and Scenes From Life on Total Loss Farm. “We’ve got six years to go on the mortgage and have always met the bill.”

In 1973, the farm supported over a dozen people on an estimated $10,000 a year. Most of the farm’s early residents were writers and anti-war activists who had dropped out of graduate school in Boston and New York City. Friends invited friends; there was a gradual accumulation of people looking to create a new way of living that broke with the rigid conventionality of postwar America. Their primary interests were learning to live off the land, making art of various kinds, and of course, hanging out. The prevailing economic theory that governed the place was: share. That was pretty much it. No one was obliged to do anything in particular, and no one in particular was in charge.

“The way it worked was, if you had a job in town, you were expected to contribute financially,” recalled Wizansky. “But if you spent the day in the garden, that was a contribution, too. I always had to remember that, because I worked in town — and there were other forms of work that we recognized, beyond those that generated money.”

“Our records are chaotic,” my dad wrote in Home Comfort. “Money is spent as it comes in. Sporadically. Sometimes we’ve got thousands of dollars in our chequing account. Other times you can’t even find loose change under the cushions of the couch. The chequebook is accessible to all and we trust each other not to make unnecessary expenditures… We tend not to get petty about the outflow of petty cash.”

Such structure, or lack thereof, makes me wonder about one of the most important assumptions of capitalism: self-interest. In Adam Smith’s canonical 1776 book The Wealth of Nations, he writes, “It is the interest of every man to live as much at his ease as he can; and if his emoluments are to be precisely the same, whether he does, or does not perform some very laborious duty, it is certainly his interest…either to neglect it altogether, or…to perform it in a careless and slovenly a manner.”

In a way, Total Loss didn’t work because the people there thought it was a model for what the world should look like. It worked because it wasn’t part of that world.

If you don’t have to do anything, wouldn’t you not do anything? Of course, the commune’s ideology held that doing something need not be quantified in dollars, which I appreciate even if it’s barely feasible in the world I live in. But wasn’t this idea ever taken too far? Did self-interest ever undermine the commune’s spirit of tolerance?

“Oh, we had many problems with freeloaders,” recalled Wizansky. “They were often expunged! We’d have these big meetings, and people would air their grievances. That’s often how people were asked to leave.” Without a formal process by which people contributed, goodwill and social acceptance were commodities that could earn a person room and board for months — even years. “Making yourself fit in with the group, finding a place for yourself that worked — that absolutely was a commodity,” agreed Wizansky.

In a way, Total Loss didn’t work because the people there thought it was a model for what the world should look like. It worked because it wasn’t part of that world. The farm’s hilltop is magnificent, and the birds seem to sing louder there than elsewhere, and the people who lived there stubbornly insisted that it did not run by the same rational, material logic that governs the rest of the world.

—

I grew up like a kind of expat, both inside and outside the commune. Throughout my childhood in the ’80s, Packer Corners was the center of my ideological and emotional universe. But I sometimes felt like an emissary from the consumer world when I was there.

Yet while I was out in the malls of North America, I felt like a visitor from another place. Faced with something considered “cool” by my peers (say, the New Kids on the Block, or clove cigarettes, or attending a middle school dance), my first thought would be, “What would they think at Packer Corners?” I wanted to shave my legs like the popular girls in fifth grade did, but I couldn’t bear to seem like a conformist.

Inexplicably, I got “asked out” a couple of times by boys in my grade school classes while I was living at Packer Corners. I rebuffed them haughtily and got a reputation for being stuck-up. This was easier to tolerate than the idea of reconciling middle school social drama with my life on the commune.

Meanwhile, my grandma Blanche took me on annual trips to the Gap in White Plains, New York, for new clothes. Before every visit, my dad would get both of us preemptive haircuts to appease her. I let Blanche pick outfits for me because I was usually too overwhelmed and intimidated to make any of my own decisions. I stayed in the changing room while she stood in the open door inspecting me and telling me to tuck things in. After shopping we would always go to Friendly’s, where I would order a “supermelt” sandwich and a “happy ending” sundae off the riveting laminated menus. I adored the entire experience.

In a way, I still think like this. Even as an adult, I find myself pulled in two different directions.

Nina, who grew up at Packer Corners (her mother was a founding member) and now works as a union organizer, expressed a similar feeling to me at the reunion. She said that growing up in a non-hierarchical community has made it hard to submit to hierarchies as an adult. This has been my experience, too. I’ve always liked to get praise from my employers, but I can’t seem to adopt their priorities as my own.

What a lot of people probably don’t realize is that the main reason people joined communes back then wasn’t economic. The late 1960s to early 1970s was the period of lowest income inequality in the United States since 1913. In other words, the middle class then possessed more of a share of wealth than at any other time. People at Packer Corners, in most cases, could afford to be poor and be, in a certain playful way, glamorous.

And it didn’t cost much to feel that you were living a good life in 1973. Many of the expenses that are essential for participating in any kind of economic activity in 2018 didn’t exist: data plans, home internet, healthcare. “We didn’t have health insurance,” recalled Wizansky. “If you needed to see a doctor, there were a few hippie doctors in town who would see you for cheap. There was one doctor who always seemed to be losing his records. And then there was the option to just…not pay.”

This was also a time before the modern Age of Debt, and that gave people more freedom. “Oh, I don’t recall anyone having any debt to speak of,” Wizansky told me. “People didn’t have student loans, and no one used credit cards.”

The way I’ve come to see it, at its peak Packer Corners was a dream of charismatic self-sufficiency made possible by a singularly prosperous moment in time.

The sociologist Benjamin Zabloki conducted a large survey of American communes in 1980 and found that, among members of rural communes, 44% reported ideological reasons for joining a commune; only 10% reported economic reasons. The way I’ve come to see it, at its peak Packer Corners was a dream of charismatic self-sufficiency made possible by a singularly prosperous moment in time. Its promise of a way of living where the strength of one’s personality or artistic vision could substitute for money buoyed so many young people forward. It put a sweet taste in their mouths, enabled their dreams, and maybe that helped some of them endure — and thrive — during the increasingly breakneck capitalism of the ’80s and ’90s. It certainly gave them a narrative on which many of them continue to hang their hats.

It wasn’t the same for people who came of age later. Hippies of the ’90s had a harder edge than the originals; life was already measurably less kind even in the early Clinton years. My dad let a couple of Gen X hippies live in the cabin he built for a few years, and in 1999 they had a baby, born on the cabin floor. This couple tried starting a tincture business out of the cabin’s tiny kitchen.

Years later, when I cleaned out the cabin after they had left, I found the remnants of their efforts amid sedimentary layers of trash. I hauled nine pickup truck loads of trash to the dump; it cost me hundreds of dollars. In rural areas without garbage pickup, you pay to dump your trash by weight. This is why poor people sometimes have old appliances in their yard; disposing of heavy things is expensive. The trash halo around my cabin was my first material indication that being a hippie was not what it used to be.

—

As I make my own way in the aftermath of the counterculture, I can’t entertain the narratives pushed forward by life on the commune. Everything I do costs money; it’s expenses all the way down. The way I see it, the only way to afford to go off the grid and live a back-to-the-land lifestyle in 2018 is to be very wealthy. Just ask the #vanlife influencers on Instagram; it takes a lot of money to look that cheap. The 1960s counterculture was in conversation with the prevailing social conventions of its time: the moral regime of the nuclear family, Fordist rationalization in the workplace, racism and sexism at every level, and neoliberal warmongering abroad.

But that’s not the conversation we’re having right now. Ours is more of a struggle to survive in a brutal social and economic system that favours corporate profit over individual health and self-determination. I love to share my earnings in 2018 — as a taxpayer, with my fellow Canadian citizens, in funding a society with benevolent social benefits like universal health care and affordable higher education.

But communalism and radical self-determination, it turns out, can be exhausting. Maybe even more exhausting than a nine-to-five job.

If I were to start a commune today, it would be in the hopes of changing the economics of my world, not its social rules. I would want to share expenses, spend ethically, and subvert the systems of financial inequality that dominate the lives of most Americans. I would want to create new models of ownership, not new models of domesticity — because I’m not particularly concerned that our sexual mores are too repressed, but I’d find it a relief to lower my monthly housing expense.

In the ’60s, hippies didn’t trust their government, but today I yearn for a government willing to stand up to corporate interests. The hippies didn’t believe in the emancipatory potential of middle-class consumption habits. I don’t believe that I’ll be emancipated by a so-called sharing economy meant to enrich tech companies at the expense of vulnerable people. Ultimately, I don’t think that it’s possible to subvert a system of inequality of any kind in 2018 without factoring in the expenses accrued by everyone.

That’s what puts me at odds with the legacy of my father’s commune.

Many kids raised by hippies have told stories of trauma and neglect, and I’m fortunate not to have any such experience. The consequence, for me, of having grown up in an intentional community that no longer exists is a feeling of being an observer, an outsider, everywhere I go. I’m still, as I said, an expat from another world. I know that every human feels this way sometimes, but I suspect that children of intentional communities feel it a little more acutely. There’s an Italian coffee shop that I love to go to, where everyone seems to know one another. Instead of reading my book, I often sit and watch the other patrons and wonder what it must be like to go into a coffee shop and think, “These people are my people.” The only time I feel that way is twice a year at the Packer Corners trustee meetings.

So at the 50th reunion, I felt sometimes ambivalent, and at moments full of despair. This tiny social construct on a Vermont hilltop is my home country. These are the people who taught me my most precious skills, like how to have fun while doing a mountain of dishes, or how to disarm a new acquaintance with informality. I can trace almost all of my strong opinions back to this place.

But communalism and radical self-determination, it turns out, can be exhausting. Maybe even more exhausting than a nine-to-five job. A lot of people at Total Loss burned out and left after a few months or years, citing fatigue of one kind or another. For years I heard women grumbling about how few men volunteered for dish duty; men with upper body strength grew wary of being tapped for every single act of heavy lifting that 80 acres commanded. Sometimes living by improvisation is freedom, sometimes, it turns out, it’s imprisonment.

Capitalism is a tragically flawed governing system, and I’d love to opt out of it. But I wouldn’t prefer a nebulous and highly subjective alternative model where some things cost money and others, inexplicably, don’t.

By the time I was born, most of the original founders of the farm had moved away. My dad moved into town in the mid-’90s; three decades of commune life was enough for him. At the very least, the function of money is that it has a fixed value that a society agrees upon. Without it, we’re left to our own devices to decide who’s pulling their weight and whether we’re getting our fair share.

Several years after my dad’s death in 2005, I became a trustee — partly out of a sense of duty, partly because I liked doing what the commune was created to do: sitting around in the old living room once or twice a year with a bunch of people I’ve known since I was born, drinking coffee out of the familiar old handmade mugs and discussing things like who’s going to mow the west field in spring. The board now consists of eight people, half of whom are Packer Corners founders, and more than half of whom are well over 50. Each trustee pays an equal share of the annual property taxes — around $500 each.

For the five founding members still on the board, the farm retains a mythical importance as a safe haven for artists and weirdos. But it’s different for me and Matt, Nina’s husband who took a seat on the board when she didn’t want to, who also lives in a city with their family. We visit the farm when we can, but its existence as an artistic hidey-hole is, at this point in our lives, immaterial. Matt and I worry that in 20 years — at which point, goddess willing, we’ll be paying off our children’s post-secondary degrees — we will also be left holding the bag at Packer Corners. It will be up to us to continue to fund a nonprofit built on the dreams and memories of the generation that came before us. When I consider this future, my father’s commune, and the magic it once enabled, feels like a millstone around my neck.

My life out in the capitalistic rat race is far from perfect — and I’m lucky to live in Canada, with its free health care. I have student loan debt, credit card debt, graduate school tuition, and two kids’ summer camp fees to keep me hastily hopping-to in the labour market. The best things in life are still free, but I can’t enjoy most of those things without paying the rent and keeping the creditors happy. I wish I didn’t have so many bills to pay, but I’m willing to keep working to pay them. I don’t like my records to be “chaotic,” and I like the personal accountability that comes with working for an income.

Capitalism is a tragically flawed governing system, and I’d love to opt out of it. But I wouldn’t prefer a nebulous and highly subjective alternative model where some things cost money and others, inexplicably, don’t. I like to be able to see the relationship between money and things. If Matt agrees, maybe we’ll donate the 80 acres to a conservation group and let nature reclaim it completely. Marty didn’t want to tend his parents’ garden, he wanted to plant his own. I can relate.

Some names were changed to protect the privacy of people appearing in this story. Photos by Harry Saxman.

Wealthsimple's education team is made up of writers and financial experts dedicated to making the world of finance easy to understand and not-at-all boring to read.