Money Diaries

Karen Russell: A Brutally Honest Accounting of Writing, Money, and Motherhood

The novelist didn’t realize how fervently society wants to turn us into calculators — every action has a payment or a fee — until she had her first child. Here she reckons with motherhood’s ticking meter: every minute with her kids is work lost, and each minute writing subtracts from precious, un-price-able joy.

Wealthsimple makes powerful financial tools to help you grow and manage your money. Learn more

The Meter Keeps Ticking

Today, I am thirty-seven weeks pregnant with our second child. I promised to turn in a draft of this piece before the end of the week. I just dropped off our first child, a two-and-a-half-year-old boy, at his daycare, which he attends part-time on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays. I’m drinking coffee that I purchased at the gas station, $2.59 for a bucket-sized cup; the flavour was labelled “Turbo.” Now I feel like there is a blinding sunrise happening inside my mind. Coffee has turned the baby inside me into a fetal ninja, but it has not yet helped me to find the words I need, or my rhythm on the page.

At the moment I am our family’s “breadwinner,” to use a compound noun that evokes the Brothers Grimm, and also a lottery held during a famine. Writing has always been a matter of survival for me; becoming a mother has not changed that. But a book in utero feels dangerous to me in a new way now: it’s a hungry ghost on the desktop, a succubus draining security and attention from my real babies. An unfinished book — yawning, open, blank — is still the mouth I want to feed. Soon we’ll also be responsible for feeding two children.

On a daycare morning, like this one, I think about my toddler son near constantly. I worry that my writing days have an emotional cost to him that I sometimes project to be very high, and always pray will be offset by what he gains, also incalculable at this early hour, by attending a good daycare. What I can tally to the penny is the actual dollar cost to our family: $1,200 a month, $300 a week, $100 a day. When I fixate on this math, I begin to have the panicked sense that I gave up time with my son to delete three paragraphs; suddenly writing badly feels like stealing from him. This is obviously not a healthy way to approach creative work, or a pressure that yields good fiction, at least in my case.

Sometimes when I’m writing I’ll get the panicked sense that I gave up time with my son just to delete three paragraphs.

A secret hope of mine, which I now find hilarious: I imagined that once I had a child, I would become a faster writer. Faster, and also better. It’s hard for me to reconstruct the optimistic logic that led me to this hypothesis. I think I honestly believed that if I did not have the option to write badly, I would simply evolve, like that Lamarckian giraffe, into a more efficient creature. Instead, for a long time after my son’s birth, I stumbled through a hormonal fog. We still aren’t sleeping much in this house. Many days, I feel like my mind has become one of those crane hands you see at arcades and truck stops, grasping arthritically at the air above the sunken prizes.

“Hey, Tony,” I asked my husband in the next room the other night. “What is that word we use in English for the queen’s house?”

“The castle?” he called back, a little alarmed.

Taxis have a meter that charges per mile when moving and per minute when idling. These days, I find myself thinking about the taxi meter often as I stare at the blinking cursor. I feel like the passenger in a stalled cab — watching as the cost of idling rises, my stomach muscles tensing. As I sit here now, I am waiting for some mental congestion to clear so that I can, please God, find the on-ramp to my own imagination.

It’s Tuesday morning, 9:32 a.m. In six hours, I will leave to pick up our son. I am aware — although I powerfully wish that I could turn this awareness off — of the ticking clock.

Does the World Need Another Book?

At 10:40 a.m. an email arrives from my son’s daycare; it’s a photograph of him holding a pink pipe cleaner and a toilet paper roll. With an electrician’s focus, he is touching the fuzzy antennae to the cardboard. The caption reads: “Oscar experiments with different ways to thread a pipe cleaner through a hole!”

Sign up for our weekly non-boring newsletter about money, markets, and more.

By providing your email, you are consenting to receive communications from Wealthsimple Media Inc. Visit our Privacy Policy for more info, or contact us at privacy@wealthsimple.com or 80 Spadina Ave., Toronto, ON.

Perhaps you, like me, are wondering: there is more than one way?

Before I became a parent, writing was the priority that designed the shape of my life. In my early twenties, I sold my first novel on the strength of a proposal and spent the next four years in a state of low-grade panic, trying to figure out how to write it. My overhead was very low. I lived in various sublets and shared apartments, I worked as a receptionist at a veterinary clinic on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, I taught as an adjunct professor of creative writing. (At $17/hour, I made much more as a vet tech in my puppy scrubs than I did as an adjunct. A colleague of mine calculated that she made $7 per hour teaching literature to undergraduates who paid $55,000 annually to attend their Ivy League university.)

Recently, I published a story in a well-regarded literary journal that took me, from start to finish, three years. I was paid very well for a short story: $1,500.

Back then I could still pull all-nighters, and my favourite time to write was in the dead of the night, after I’d failed to meet some daytime benchmark — a failure that paradoxically liberated me to enjoy writing again. Having outlasted any reasonable expectation of productivity, I felt free to play, free to riff in the dark. Snowflakes percolated outside my apartment window while words accumulated on my glowing screen. What was going to stick? There’s no way of knowing this at four a.m. In that state of self-hypnosis, the ticking meter is inaudible.

After I published my first book, I was lucky enough to string together a series of visiting teaching gigs, each a semester in length. Columbia University, Bryn Mawr College, Williams College, Rutgers University in Camden, the Iowa Writer’s Workshop. Even as I dreaded moving every year, I was relieved and grateful to have these positions. For over a decade, I chose to live this way, riding my version of a Mary Poppins umbrella, a Toyota shellacked with university parking stickers, from one state to another. I didn’t have health or retirement benefits, or a forwarding address, but I was rich in time to do my own work.

A book is not a product like a shoe, or a toaster. Very few of the thousands of books that are published each year will be profitable — not for their publishers, and not for their authors. Seven out of ten titles do not earn back their advance. Most writers will not receive royalties. A book advance is a finite lump sum, paid out in installments, and as Roy Blount Jr. explained in the New York Times, the coy figures reported when Publisher’s Lunch announces book deals — “high six-figures,” “low six-figures” — can sound larger than they actually reveal themselves to be: “That may mean $100,000, minus 15% agent’s commission and self-employment tax, and if we’re comparing it to a salary let us recall that it does not include any fringes like a desk, let alone health insurance, and that the book might take two years to write and three years to get published. . . .” Blount writes. “So a six-figure advance, while in my experience gratefully received, is not necessarily enough, in itself, for most adults to live on.”

If you are published by a small press, you might receive an advance in the low thousands of dollars. My husband works as a book editor for an excellent independent press here in Portland, Oregon, Tin House Books, which simply does not have the capital to offer six-figure advances. Books of extraordinary quality, books that took their authors half a decade to complete, regularly sell to both indie and commercial publishers for less than a used Buick LeSabre.

It’s a minority of writers who are able to benefit from the circuit of speaking gigs, visiting professorships, and fellowships endowed by the generous dead. I have been one of them, to my own great surprise — in 2013, I received a call from an unknown number; my car had recently been stolen, and I believed the police were about to inform me that its flaming chassis had been recovered in some distant area code. Instead, I learned that I’d been awarded a MacArthur Foundation fellowship. These are five-year grants, paid out in $125,000 annual installments. I knew about this fellowship, but I never so much as fantasized that I might receive one. (Who expects good news to come from an unknown number? I’ll tell you what, I take a lot of robocalls now). After years of jellyfish drift, floating from job to job, I was suddenly able to put down a root. I paid off medical bills, made a downpayment on a home. And from this new vantage, I feel an ever-deepening appreciation for the work that writers and artists do, often under extreme financial duress.

Writing a book is a mad gamble for anybody, but the dice are weighted. While I’m proud of the work I’ve done, I also know so many brilliant and deserving writers never get to experience a minute of this kind of freedom. The success of some authors and the obscurity of others often mystifies me, even as our country's bedrock racism and widening income inequality make certain outcomes grimly predictable. The world of publishing is still overwhelmingly white, and entry-level publishing jobs and internships, with their notoriously low salaries, can be out of reach for those without another source of financial support. The same applies to MFA programs, where even the largest stipends rarely cover both tuition and rent.

When we talk about wealth inequality in our society, the shadow conversation is always temporal inequality.

Why does anybody want to write? I think that answer can be opaque even to the writer — as mysterious and powerful as love, as irrational and foolish as love, as brutal and animal as a salmon run. “If you can do something else, anything else,” an undergraduate professor of mine once advised me, “do that.” “The world doesn’t need another book.” But let me tell you, with a baby’s head pushing down on my pelvis — there is something analogous about these two states, being with book and being with child. Your entire organism will fight to translate a fetus into a newborn, an imaginary cosmos into a book with a spine. How to do it — how to make a living doing it — that’s the question that relentlessly haunts the writers and artists I know.

Writing is a hustle for every single one of them. One of my friends works as a labour organizer, another as a ghostwriter. An essayist I love deejays sets at Dig a Pony, a bar here in Portland. My husband acquires and edits epic four-hundred page poetry manuscripts, slim novels in translation. I write short stories, some of which stall out on my desktop for months or even years before I figure out how to finish them. Recently, I published a story in a well-regarded literary journal that took me, from start to finish, three years to sort out. At last, I arrived at a draft that felt complete to me. I was paid very well for a short story: $1,500. But you see from simple division why very few fiction writers can support their families with their writing alone.

The Eternal Present, The Relentless Grind

Our Navy dad grew up poor in Sarasota, Florida, and he reminded me and my siblings constantly of our many advantages. One afternoon, while I was sitting on the bait cooler reading Bram Stoker, he looked up from gutting a red snapper and told me, “Karen, the only reason you can imagine anything at all is because you have food in your belly.” I try not to forget this. If you’re afraid that you can’t pay rent, or buy groceries for your family, there is no surplus energy to burn inside a dream.

Recommended for you

At the moment, I am on leave from a three-year visiting position at Texas State, preparing for a self-funded maternity leave made possible by the sale of a recent book and savings from the MacArthur Foundation fellowship. To say this grant had a “life-changing” impact on me is a cliche and also an understatement. It stamped my passport to go to new imaginary worlds, to make experimental work across genres; I was able to finish one book and research and begin a second; I gave myself time to collaborate with an opera composer and a ballet choreographer, to work for causes that matter deeply to me.

But the greatest risk this award enabled me to take is an incredibly common one: that irreversible decision of starting a family. “Not an egg you can unscramble,” as a friend told me. In the uncontrolled experiment of one’s own life, it’s impossible to know exactly how the story would have otherwise played out. What I can tell you without reservation: had I not received this grant, the decision to have two children would have been a more difficult one, as would my experience of pregnancy, delivery, and parental leave.

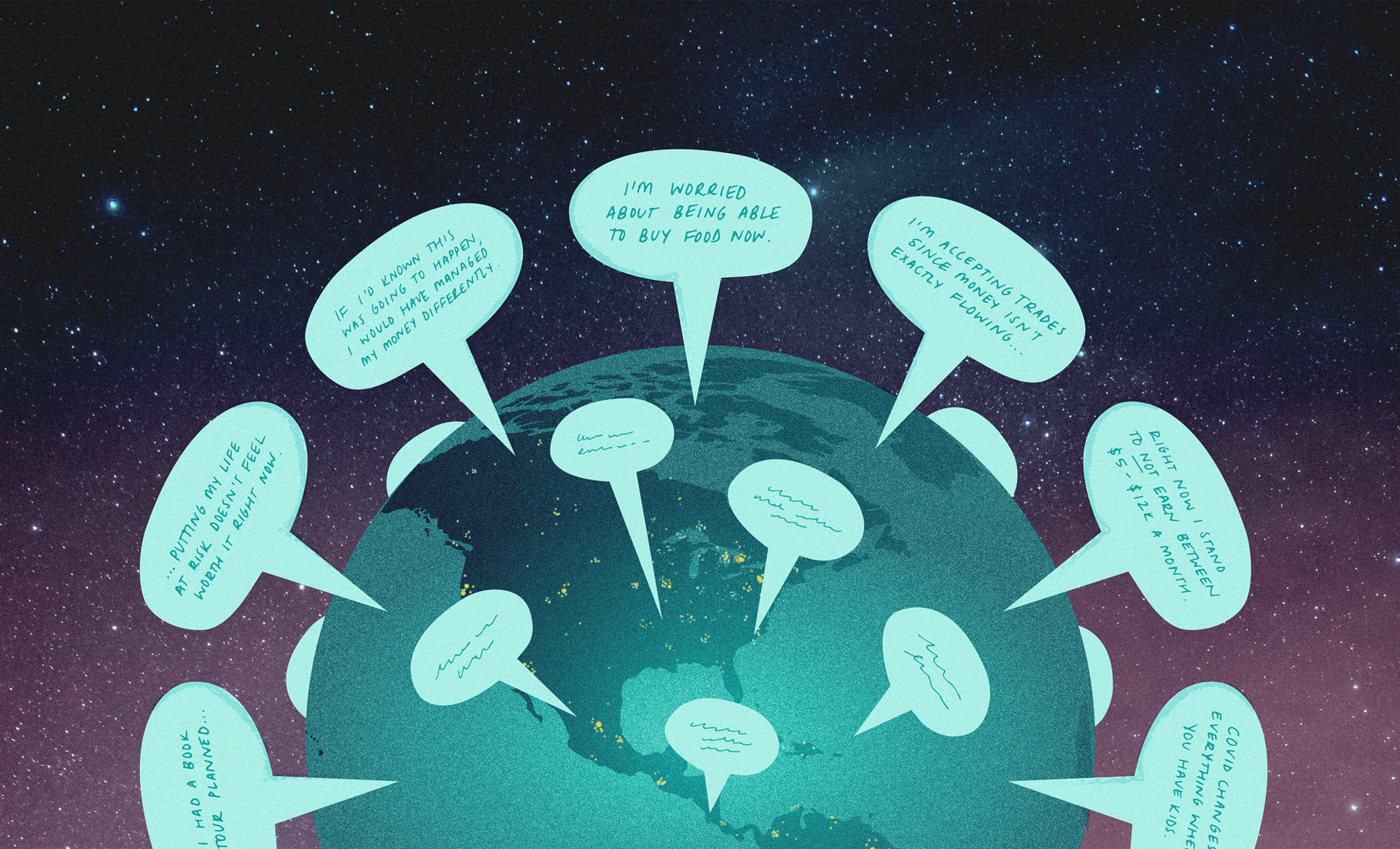

Perhaps the most revelatory gift of the MacArthur fellowship was discovering how expansive time becomes when you feel that you can afford to take a breath. During those early months with my newborn son, I got to experience time as it so rarely moves in our economy — unmetered hours, untethered to profit. I am grateful in my marrow; I also find myself viscerally outraged that so few people are ever able to live in time this way, to meet their infant’s gaze without a ticker tape of terrifying numbers running through their head. 25% of working mothers in America return to work within two weeks of giving birth. “I ran the numbers and I couldn’t take any more time off,” said my friend Sylvia, a waitress who spent six weeks with her newborn. The alchemical dictum, “time is money,” turns out to have this cruelly straightforward consequence. When we talk about wealth inequality in our society, the shadow conversation is always temporal inequality.

We learn that there is a dollar cost and a dollar reward to everything we do. But there is a cost, also, to living in terror of an unprofitable moment.

If you are panicked about money, an hour can feel like a cramped tunnel. There is a shrill dissonance between “the eternal present of childhood” — the dawn world to which children reintroduce their parents — and the relentless grind of capitalism. I know that my struggle with the new meter is, in itself, a true luxury in an economy where so many parents cannot afford to spend time with their children, while many others cannot afford to return to work because of childcare costs.

One of my best friends is an acclaimed journalist and recently-divorced mother of a four-year-old son. As a contributing writer for the New York Times, she makes $50,000 a year and receives no benefits. Her rent for a two-bedroom apartment is $1,800 a month; the cheapest childcare she could find costs $1,200 a month. “My son is eating Doritos and watching cartoons in a basement right now,” she told me. “That’s the best I can do for him.” Her father, a machinist in Fort Lauderdale, sends her his social security checks. She is struggling to make ends meet despite writing for the most prestigious paper in the world, and is actively looking for a second job.

A graduate student of mine at Texas State, the mother of two young sons, continued to send me drafts of new work from an isolation room in St. Petersburg, Russia, where she’d travelled to receive treatments for her MS not covered by her insurance. Like so many people who are failed by our insurance system, she turned to GoFundMe to pay for her medical care, raising $45,000 towards an $89,000 bill. Her first publication recently appeared in The Atlantic; she revised it while recovering from chemotherapy.

I know so many parents filled with these same warring urgencies: a powerful love for their children, a wish to be present with them, an imperative to provide monetarily for them, and a hunger to make art — lunging forces that are rarely in alignment. And unlike me, they have not received support from any grant or institution. They do this work without a net to catch them.

Monsters Inc.

The same tug-of-war that leads me to queue up pictures of my son when I should be working on a novel also causes me, on the days I spend with him at home, to pray that he will nap for an extra 30 minutes, so that I might, for example, finish two more paragraphs of this essay. The irony of wishing that my real son would sleep so that I can write about his avatar is not lost on me; what I find even more disorienting is my simultaneous wish that I could crawl into bed with him right now, and feel his warm breath on my neck, instead of writing this to you. For as long as I’ve been alive, I’ve known that it was possible to feel bereft and exhilarated and weary and stimulated and guilty and relieved. But I couldn’t have imagined, even a few years ago, that these acutely contradictory emotions could become one’s baseline state. This is one of many lessons that my son is teaching me.

It’s hard to feel these extreme weathers colliding in my body without thinking the word monster. There is a real temptation, for all women in our culture — those who want children and those who don’t, those who work outside the home and those who are full-time caretakers — to label themselves as such. Shame can feel so private and individual that it becomes difficult to recognize its pernicious consequences at the level of a society, its role in maintaining a bitterly unequal status quo. Mothers in particular are shamed for any and every choice they make related to work and children; and shame can make a family’s financial struggles feel like a personal failure, instead of a societal one. Despite broad support for public K-12 education, most working parents in the U.S. are still on their own to figure out and pay for child care for these most critical years, the sunrise of the mind, ages zero to five. In 28 states and the District of Columbia, the average cost of enrolling one child in daycare, roughly $9,000 a year, exceeds the cost of public college tuition. Child-care workers in America, meanwhile, make a median hourly wage of $10.31.

Perhaps this will change in the near future. There’s now mounting support for federally-subsidized universal child care. The case is usually made in economic terms, citing staggering statistics like this one: the cost of our child care crisis to the U.S., in lost productivity, is estimated to be $4.4 billion.

But there are other, ghostlier losses, harder to tally. When someone like Elizabeth Warren talks about mothers leaving the workforce, artists and writers, who are often self-employed, might not be the first demographic that jumps to mind. They are the secret incubators of unborn worlds, but their contribution can be easily dismissed if you’re just going by the numbers. The softly-rippling impact of a book, an essay, a story, a poem, isn’t calculable in figures. I think about my students with young children, my friends who are single parents and uninsured freelancers. I think about the authors we haven’t read yet, whose books may never exist, because they do not have the space, literal and figurative, to birth their worlds onto paper. I think about mothers in particular, because the burden of childcare still falls disproportionately on women’s shoulders. These writers have unwritten libraries housed inside them, voices trapped inside the walls of our present system.

Who gets to live a spacious hour? Who gets to spend time with their children, and time doing work that fulfills them? Raising children, writing books: risk is built into both undertakings. But I can’t help thinking that they shouldn’t feel quite this risky — that the low ceiling of dread so many of my friends and colleagues and students live under would begin to lift if health and child care were universally available. Everyone deserves this kind of radically free time — time underwritten by the security that comes from knowing your young children are safe, that a totalled car or medical emergency won’t send you hurtling towards the abyss. It shouldn’t take a windfall to make this possible.

What’s Actually a Luxury?

It’s now 3:02 p.m. Two miles down the road, my son’s pudgy hand is moving rainbow beads along an abacus, under his teacher’s supervision. In nine minutes, I need to leave to get him. I didn’t get as far as I’d hoped to in this draft, and like all of you, I imagine, I’m always hungry for more time. Three years ago, when I became pregnant with my son, I believed, in a misty way, that his birth would provoke many transformations. What I failed to guess was how profound these changes would be — it wasn’t simply that I had less time to write, time had become an entirely new substrate. I weigh risk in a different way now, in both my “real” and my imaginary lives. Parents talk about the pressure to provide for their children, but this isn’t something I’ve heard many writers who are also parents discuss — the way that children change their approach to creative work, the kinds of stories they attempt to tell, their threshold for artistic risk. As I work on my book, I see the face of my son in the side mirror, the face of our future daughter. Writing for a living has always been a faith game, and a child makes the maintenance of that faith infinitely more challenging.

With our new daughter coming, I’ve been grappling with this anxiety, its mammalian intensity, the way it seems to swell in lockstep with my second pregnancy, while hoping to God that it doesn’t sound as if I’m complaining about the difficulty of making a living as a writer after all the support I’ve been given. It’s a privilege to get to do this; it’s the only job I’ve ever wanted. Relative to so many families in America, we are in an excellent position. And yet kids make the darkest hypotheticals feel viscerally plausible, and the world of publishing is in flux at the moment. We’re living in an era of accelerated obsolescence, but books still turtle into being on their own slow timetable (much slower, in my experience, than babies). This year, my husband is transitioning to part-time and freelance work, and my visiting professorship ends in May 2020. The cost of childcare will soon exceed our mortgage, as it does for so many families. Perhaps because I have benefitted so much from unexpected generosity, I am very cognizant of how quickly another kind of lightning strike could take it all away. A prolonged period of unemployment. One accident. One illness. During my son’s pregnancy, my insurer, the Oregon Co-op, folded four months before my due date, and we scrambled to find coverage. In the end, I was able to buy insurance on the Obamacare marketplace; our out of pocket cost for an uncomplicated vaginal delivery was $7,000. A C-section would have cost double; a NICU hospitalization, $3,000 each day.

How do you turn off the meter, once you become a parent, once you make the really audacious decision to host dependents on this planet? Or is it possible to attenuate to it, like an alarm that’s always bleating?

Whoever you are, whether or not you have kids, I imagine you’re no stranger to some version of this meter. I don’t think you can grow up in America and avoid its installation; our economic system turns humans into calculators. From an early age, most of us learn that there is a dollar cost and a dollar reward to everything we do. But there is a cost, also, to living like this — racing the clock, in terror of an unprofitable moment.

One of the reasons I’m a reader is because books give access to this deep, still time, where years can unfold in a quarter-hour, where the fossils of thoughts are suspended in amber, where people fall in love and die and flowers flower at the speed of your reading, the whole cosmos moving only as fast as your own eyes across the paper.

One of the reasons I love being a mother is because my son is teaching me how to live in time again. I love the days I spend at home with him. In the winter, the rainy green light makes our living room feel like a submarine. In the summer, time moves like water across a floodplain, the sunshine spilling endlessly onward. When I think about losing a day with him, my throat closes. Simultaneously, I crave writing time like oxygen. I know there are other amphibians like me out there, alternating lungs and gills, navigating the murky liminal zone between “work” and “home.”

In an earlier draft of this essay, I wrote that “It has been a luxury to make decisions for myself and for my family that are not exclusively driven and determined by money.” Then I reread that draft and realized that I’d used the word “luxury” 14 times. I was struck by my blind repetition of this particular noun. Is it possible to acknowledge one’s privilege while simultaneously reimagining the lexicon? Working to redefine these things — pursuing a degree, insuring one’s family, taking parental leave, educating young children — not as luxuries and lucky strikes, the jackpot of the affluent, but as universal rights

For someone who imagines things for a living, who is allegedly a “creative person,” I find that it takes real work to imagine this: a world where time moves a little more freely for the millions of families who feel squeezed; where those “luxuries” like parental leave and quality childcare available to some of us “lucky” ones become the expectations of an entire generation. Where it is possible to make art, make a living, and raise children on another clock entirely.

Karen Russell won two National Magazine Awards for fiction, and her first novel, Swamplandia! (2011), was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and one of The New York Times’ Ten Best Books of 2011. She has received a MacArthur Fellowship and a Guggenheim award among others. Born and raised in Miami, Florida, she now lives in Portland, Oregon and is a visiting professor at Texas State University’s MFA program. Oh, and she actually had her baby before she finished this essay! A girl named Ada Starling Perez.