Money Diaries

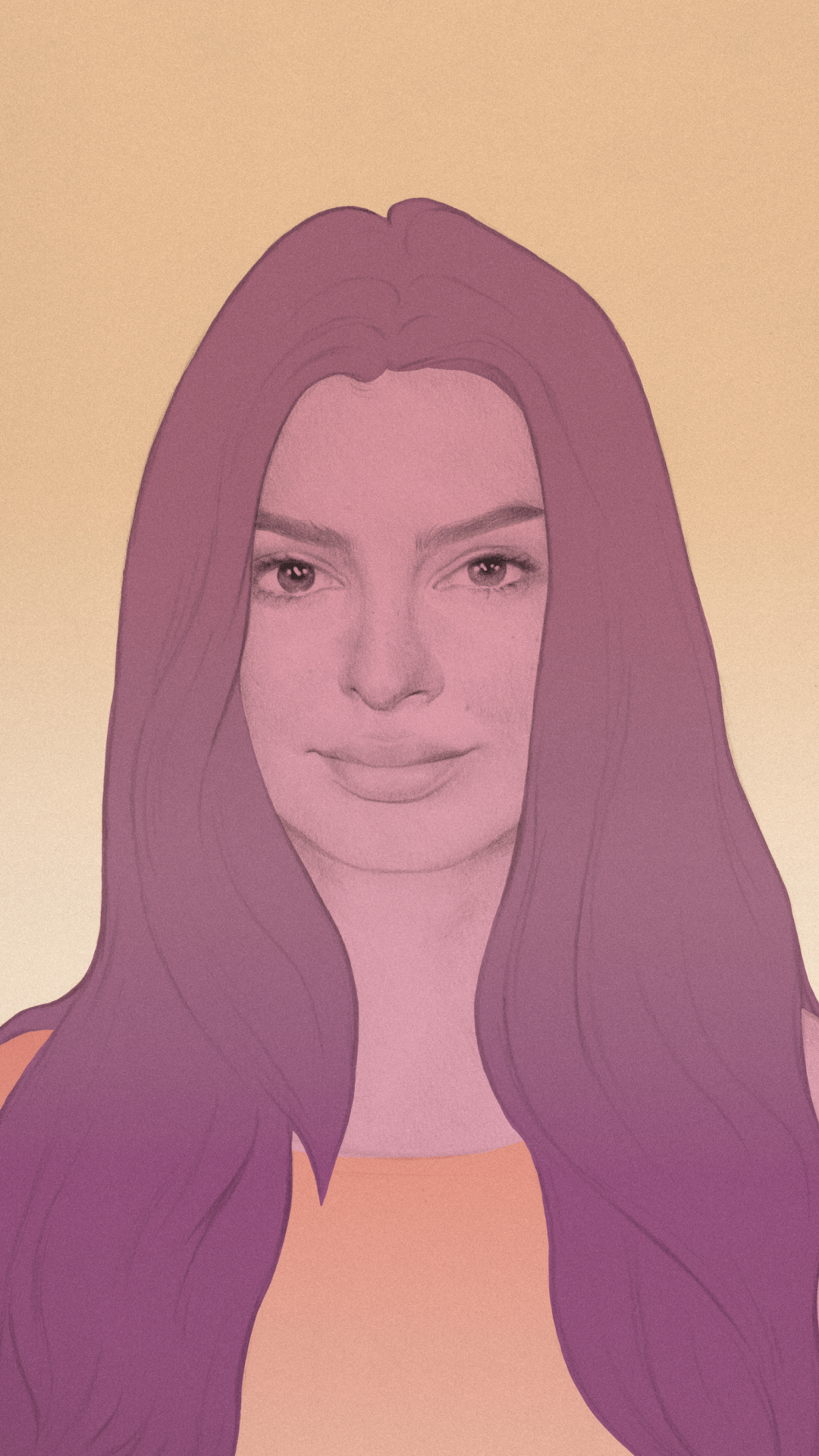

Emily Ratajkowski Is Not a Commodity

The actress, model and now writer tells us her money story, and all the intense contradictions about objectification it entails.

Wealthsimple makes powerful financial tools to help you grow and manage your money. Learn more

For years, Emily Ratajkowski worked in an industry where your body is your most bankable asset. She’s been paid to sell cars and bikinis and hamburgers and couture with it. She’s been paid to pose topless in shampoo ads and danced nearly nude in Robin Thicke’s infamous “Blurred Lines” music video. It’s been an enormously lucrative career, and her younger self considered those choices empowering — and said so. Now, she says, it’s a bit more complicated.

EmRata has emerged as a vocal critic of the ways society commodifies women’s bodies. She’s been abused, assaulted, and disrespected as she’s moved up the ranks of the modelling industry. Yet she’s also made a fortune, earning herself not just money but power and influence — and 28.5 million Instagram followers. In her first book, an essay collection aptly called “My Body,” she delves into that contradiction, and reckons with how much making a living as an object of desire has really cost her.

Wealthsimple: In the book, you talk about knowing that you were an object of desire at a very young age — a teacher in middle school snapping your bra, for example. But it also seems like, from very early on, you understood that money meant power. And you started working as a model when you were 14, and never really stopped. How did you come to understand that relationship so early?

Ratajkowski: I just recognized that my friends who had their own money, and access to money, had more freedom. In high school, I saw that a lot. My friends who had cash from tips, or had a job, it seems like they were just more able to do what they wanted when they wanted, and that really impressed me. I graduated high school in 2009, a year after the financial crash, and I think that was very impactful to my understanding around money and security. The way that my parents were thinking about my future in college felt different than what I wanted, which was security. They had different ideas about what that looks like. And it kind of shook up the way that I thought about setting out into the world.

What were their ideas?

Yeah, I mean, they’re boomers, and they prescribe to the notion that you go to college and then you get a job and that’s how it goes. And I had older friends who were graduating and had insane student loan debt. And I was applying to a lot of public universities, but also private universities and just was thinking about the astronomical debt that I would be in going to school. And I was interested in subjects like art and writing — things that don’t guarantee financial security or job placement. And after doing a year majoring in art, it became very clear to me that that just wasn’t the right path. And I was just more interested in having the security that modelling offered.

You write in “My Body” about some truly harrowing experiences in the modelling industry, and at the same time it seems like you were staying focused on your goal. Which seems to like: ride the wave as far as it takes you, save money, get out, make art. And I’m wondering what kept you going in those moments when you were tested and hurt and exploited?

Financial freedom. My parents were both artists, essentially — my mom was a writer, my dad a painter. But they worked their whole life and were teachers in order to have time to do what they wanted to do. So I definitely understood that there was a financial element to it; you can’t just go off and be like, I want to make art or whatever. And I had just seen what a hard and long road it was for a lot of people to even get to a place where they could live in the city that they wanted to live in and do what they wanted to do. So modelling felt like a shortcut to me. And I still feel extremely grateful for the opportunities that it allows me, and the financial security and the ability to live in the places I wanted to live in. And honestly, I don’t think until I wrote this book did I even consider my experiences particularly difficult, or even my relationship to my body and my self worth difficult. Because I also, and I still feel this way, feel very grateful for the opportunities that have come with my career.

In your book, you reckon with being commodified by an industry in which you’ve also earned considerable wealth, power and influence. There’s a quote in the book that’s something like, “Fuck capitalism, but until it’s gone, keep getting that bag,” or something like that, which seems to sum up that conflict. Excuse my language.

No, no. I mean, I wrote it. I think my relationship to capitalism is very similar to the way I’ve commodified my body as a woman as well. I have big issues with it. There are big problems with it. But also, I absolutely want to succeed in this world, and have the security that comes with success. Angela Davis sells her books on Amazon is always the example I point to. She’s doing her very best to get her ideas out there in a world that operates in one particular way.

A lot of people get scared of that, but it’s really important to me to talk about money.

You write candidly about photographer Jonathan Leder — going to his house for a shoot, him assaulting you, and how he made money from those images for years. You were so vulnerable, and I wonder how you decide who you can trust with your body and likeness. Or maybe that’s not even a question a young model can afford to ask.

Models are taught that trust isn’t even something you should be considering or thinking about. That ultimately you are working in an industry where you are providing a service. And there are a million other young women who are better, potentially, at the way that they would check the boxes: their body, their physical appearance, whatever. And if you’re going to be difficult in any way, that is going to be a problem. One of the things you can do to give yourself a leg up is be very agreeable, and not really have opinions about things. There’s not even a conversation about trust. That’s the deal you sign up for, essentially. And when you’re 19, and you do feel really lucky and flattered by the ability to be modelling, and nervous and unsure, maybe having some imposter syndrome around whether you actually should be there. It feels like, Okay, well, something I can do to guarantee that I deserve to be here would be to blindly put your well-being in other people’s hands. And maybe even place your own safety and well-being to the side.

Has that changed? How do you make those assessments now?

I mean, I still have a really strong instinct — when someone will ask me, Oh, are you warm or cold in here? Would you like like the temperature raised or lowered? — to say I’m totally fine, even if I’m shivering. And I have to fight that instinct to just be agreeable.

How has asserting yourself in that way affected your success? Has it?

I am in a very different position. And I don’t know what the message is here. But the truth is that by being agreeable, and by maybe not having boundaries around certain things, I was able to get into a position where now I do have more power. And I am allowed to have agency and express my opinions and my thoughts and say what I want in a given situation, and people will listen to it. But that wasn’t true then. And I don’t think it is for most young women who are young actresses or models.

Last year, you published an essay in New York magazine called “Buying Myself Back,” which was their most-read piece of the year and also appears in your book. You describe buying back a picture of yourself you’d posted to Instagram from controversial artist Richard Prince, who exhibited the work at Gagosian in New York and who’s been criticized for appropriating pictures of people, mostly women, for decades. You were paid $150 for the photo, from a Sports Illustrated shoot in 2014. And he eventually sold the picture of you, back to you, for $81,000. Then in May, you turned and sold a picture of you in front of his artwork as an NFT in a Christie’s auction, and called it A Model for Redistribution. Where did that idea come from?

I had just had my baby, and I felt like everyone was talking about NFTs. There were a lot of people explaining them to me. Once I had a conceptual understanding of an NFT, it hit such a nerve with me because I had a very, very specific relationship to the internet and ownership over image. I think all women now have a complicated relationship to their image on the internet. We all have the threat of revenge porn, you don’t have to be a famous woman to experience that. I liked the idea of using an NFT to reclaim something that I had initially posted, as a way of claiming ownership over it.

And, you know, benefiting, having capital. A lot of people get scared of that, but it’s really important to me to talk about money. I was like, yeah, I want to make an NFT where I can receive compensation for my image. The irony is that since I sold it, I’ve spent about that, the amount I got for selling, on lawyers’ fees fighting paparazzi for lawsuits. So it’s a never-ending cycle.

And it sold for more than the Prince piece did, right? $175,000?

That was really satisfying. I mean, it was absolutely insane. I was maybe six weeks postpartum. I was finishing my book. And then I decided to take this on. And as someone who at one point in my life thought that I was going to be a visual artist, there was something about this as a conceptual art piece that I really loved. It felt just congruent with everything I was thinking about with the book and with myself. And so it was just a natural thing for me to do, even though it made me feel like a crazy person.

Can we talk about the part where you write about not liking showers and not liking personal hygiene? I also hate showers, and I’ve never heard anyone talk about that!

I wanted to explore every aspect of my relationship to my body, including, you know, really intimate stuff. Like, why do I not want to take care of myself sometimes?

What does power look like to you now?

Power to me now is a hard bound copy of my book. The word empowerment gets thrown around so much now, and I think about, what does that mean? Is empowerment just money? Is it a feeling? Publishing this book — and really writing it — there was just so much power in telling the truth and being as honest as I could with myself while writing it. Like brutally honest, and at times I think hard on myself, in a way that felt really clarifying and has given me a sense of power I’ve never really known before.

Okay, final question for you: why is it important to you to talk about money? Why do you talk so candidly about it in the book?

Everything revolves around money. Our entire world, friendships, relationships — money is such a huge aspect of our lives. But it’s also taboo. People don’t like to think about how much money plays into our existence. And that frustrates me because I think that it allows people to ignore power dynamics that often are damaging to women in particular. So, the more that we can talk about money in a really honest way, the better we can pull back the curtain on power.

Originally published November 11, 2021.

Katherine Laidlaw is an award-winning journalist based in Toronto. She writes for WIRED, Outside and The Atlantic, among other publications.