Money & the World

The Market Value of My Father

When the novelist Joshua Ferris’s family blew up, his mother revealed a truth: his father was worthless, a con man. A bad investment in their lives. But years later, a mysterious book about Wall Street showed up—a gift from his father—that began to change the story.

Wealthsimple makes powerful financial tools to help you grow and manage your money. Learn more

Rain was thrashing the world when the phone rang. I was living in Florida, the Lower Keys, looking out at the storm from a house on stilts. As if on a dial, the spooky air had graded from sunlit afternoon to eerie night in no time at all. Wind and lightning had swept in from the Gulf, lashing the palms and skimming the canals all down the island’s spine, that two-lane dirt road called Spanish Main, Cudjoe’s only thoroughfare.

It was Father calling from sunny Chicago. He was a stockbroker now, with a glass office and a luxury automobile.

We began discussing the concept of the price-to-earnings ratio. I was made to understand that that easily-calculated figure could, through a glass darkly, help foretell the future direction of a company’s health and its worthiness as a holding in our entirely imaginary portfolio. I was ten, maybe eleven.

“Have you been reading the book I sent you?” Father asked.

Our textbook, called “Understanding Wall Street.” With chapter titles like “What is a Share of Stock?” and “Reading the Financial Pages,” it was a straightforward primer with a cash-green cover. He sent it to me in the mail, with my name on the envelope: a rare bit of treasure to turn up in that dead metal box. The primer’s preface laid out its purely educational intent, thumbing its nose at both the free pamphlet and the get-rich-quick book that “deluded investors with false hopes of easy gains.” It was not so technical that I couldn’t follow. I’d read its first two chapters, anyway, and I told him as much.

“And what have you been learning?” Father asked.

Of course, no one ever called him Father, least of all me, but in his new guise as a patrician financier, playing the tightening spreads and whatnot, Mother deployed the elevated diction until the day when he came crashing back to earth. Then it would be “Chuck” again, “Dad” to me.

I was glad to be talking to him again; I might have answered all his questions. I wanted in on adult stuff: their workings, sources of wealth. Instead, I took a cue from the chaos of the storm.

“Are you really a stockbroker now?” I asked.

“I told you I was,” he said. “Don’t you believe me?” Father paused. “Or is it your mother who doubts me … again?”

“Will you ever pay your child support?”

“Yes, of course. Of course I’ll pay it. I owe it to her, don’t I?”

Mother had repeated many times how often Father had paid his child support since the court had ordered him to do so: zero. For this he was a deadbeat, a scumbag and a scofflaw—none of which could compete with the truly damning implication of her claim: that he was a bad dad.

“Why don’t you just pay it now, if you’re really a stockbroker?”

“Because I owe other people money, too. Look, I’ll pay it, okay? I will. But these things take time.”

He returned us to our discussion of the P/E ratio and the other fundamentals necessary for placing sound bets on an open market. “Understanding Wall Street” laid it out in much the same manner: cash flow, payout ratio, dividend yield.

It said nothing on the subject of evaluating the worthiness of a man.

♦︎

I had not always spoken with Father strictly over the phone. Once upon a time, he and Mother were married. We lived an enchanted life in the Illinois heartland. We had our customs same as everyone else. We dyed Easter eggs in spring and carved pumpkins in the fall. The leaves changed colours, and on rainy days they clung to our sneakers and the wheels of our bicycles. Father wore a beard. He had a job with an insurance outfit and Mother worked, too. Mother drove a Pinto. Father had a company car. We were happy until Sister came along. Sister was disruptive and unpleasant and more than once I suggested we get rid of her.

Our house was exactly like the other houses in that neighbourhood, only bigger and better. My bedroom was outfitted with superhero stickers and posters of football stars. Mother and Father and I, and Sister, too, were very happy and thanked God in our prayers and during church service on Sunday mornings. Then I went to school and pledged allegiance to the flag. We had no diseases or dietary restrictions, no hangovers, and no money troubles.

Then Father made a bid for the whole outfit and it backfired. Waukegan came down, Springfield came up, and they fired him in the middle and took the company car away. Mother shuddered. She had never been married to a fired man before. They had heated discussions about money, the future … a dark thing, this “future,” frightening to one accustomed solely to a bright and happy past. There was further talk of account balances, necessary postponements. Mother sitting at the kitchen table as if cast in stone, her head in her hands.

Sign up for our weekly non-boring newsletter about money, markets, and more.

By providing your email, you are consenting to receive communications from Wealthsimple Media Inc. Visit our Privacy Policy for more info, or contact us at privacy@wealthsimple.com or 80 Spadina Ave., Toronto, ON.

One night, they had a terrible fight. Sister and I left our beds and came together at the top of the stairs. I had hated Sister every minute of our lives until then. Now it seemed she had come along when she did to spare me from having to face this tumult of confusion and terror all on my own. I loved Sister. As I was thanking God for her, Father’s sharp cry pierced the air. We raced downstairs. He lay sprawled out on the kitchen floor, his face wet with tears. He wasn’t expecting us. He sat upright and took us in his arms.

♦︎

Thirty-five years later, I can find nothing in “Understanding Wall Street, 2nd Edition,” by Jeffrey B. Little and Lucien Rhodes, about the efficient-market hypothesis. It is not that kind of primer.

The idea of an efficient market interests me now as possibly providing some insight into what happened back then. Also called the “random-walk theory,” the hypothesis lurched partially into view about 120 years ago thanks to a French mathematician named Louis Bachelier and through the decades has slowly accreted verifying bits of now-common knowledge: market returns are difficult to predict; current prices reflect all available information; price swings look randomly distributed, as if determined by a coin toss. All this and more whispers of the near-certainty that, when adjusted for risk, individual investors are never going to beat the market.

As Burton G. Malkiel, one of the popularizers of the efficient-market hypothesis, puts it in his influential book “A Random Walk Down Wall Street,” “There is no evidence that anyone can generate excess returns by making consistently correct bets against the collective wisdom of the markets.”

In 1985, the year my parents divorced, Mother was collective wisdom itself: a far-reaching, all-seeing efficiency-rationality that qualified and overwhelmed my every childish intuition. Simply put, Mother was the market. I knew better than to bet against her.

So when she made it known that the asset known as Father had not panned out, it seemed only right that he should be forgotten. Who, after all, lost the company car? Father was a dreamer, perhaps even a con man. He spurned responsibility, preferring the get-rich-quick scheme to the honest day’s labour. He was poncey, too. Effete little Father, making a great show of putting on his argyle socks and grooming his beard.

Mother valued the New Man much higher. New Man arrived on the scene shortly after Father moved out. He came bearing Ur-man things—hedge clippers, fishing rods—which quickly earned him the right to spend the night.

Mother was enormously entertained by New Man, howling with laughter at his constant wit. More vital still, New Man was law enforcement. He would never accrue a debt, print his own business cards or hire a lawyer to draft incorporation papers. His idea of success was no misty monopoly dream; rather, he made his rent by means of a moral career. To Mother, that was the sexy essence of achievement in a man, and a far cry from Father’s grubby barter.

New Man was headed to Florida to fight the War on Drugs. There was no such thing as boredom in Florida. It was all outdoors all the time, and near the water, too, where a boy might fish, swim, surf, paddle and snorkel. Mother and New Man married, and we packed the contents of the house into boxes. We followed behind New Man in the moving van for two days until we came within twenty-three miles of the southernmost point of the United States.

Father was left behind.

♦︎

A child never wants to discover that a parent is a disappointment. News about Father—everything was news to me in 1985—clung to me. I could not flee it fast—or far—enough. Florida was just the place.

But a Florida of the mind—golden sandbars, leaping swordfish, the Magic Kingdom day and night—was immediately at odds with that collection of cantinas and seashell emporiums, conch-chowder shacks, off-brand gas stations and troubled loners walking the roadside, all of which flickered past our caravan as we plowed further into the Keys. A ramshackle, wind-beaten landscape, weedy and sun-bleached, its bone-white bars and motels lacking all amenity. It might have been Jamaica or the moon.

The New Man promised us our very own canal. It would be in the backyard, accessible at all times. There I might fish, swim, etc., and otherwise pursue the American boy’s dream.

When, however, we arrived at mile-marker 23, otherwise known as Cudjoe Key, and pulled into the first house on the unpaved road called Snapper Lane, what I beheld in the backyard was a green lagoon of scum and sea foam where old bobbers and dead crab parts collected with the tide. The American boy who could make any practical use of that was a better man than me. Where water was not on that island, there was untamed wild: mangrove, palm and palmetto, unnavigable thickets of sea grape and slash pine.

♦︎

The efficient-market hypothesis allows us to assign with complete confidence an arbitrary value to our partial ignorance. It is a unified theory of almost nothing. An “efficient” market would have preceded, and presided over, everything from WorldCom to WeWork—indeed, the housing bubble and the tulip craze. The hypothesis would have also applied during liquidity disruptions to the repo market (think Bear Stearns), accounting irregularities (Enron, Tyco), out-of-whack financial derivatives (Libor, Fannie Mae, Countrywide Financial), dumb deregulations stretching back to the S&L crisis and beyond, and the milder manipulations of currencies and closed-end mutual funds.

Recommended for you

Prediction Markets Are, Suddenly, Everywhere. Wall Street Wants In

Money & the World

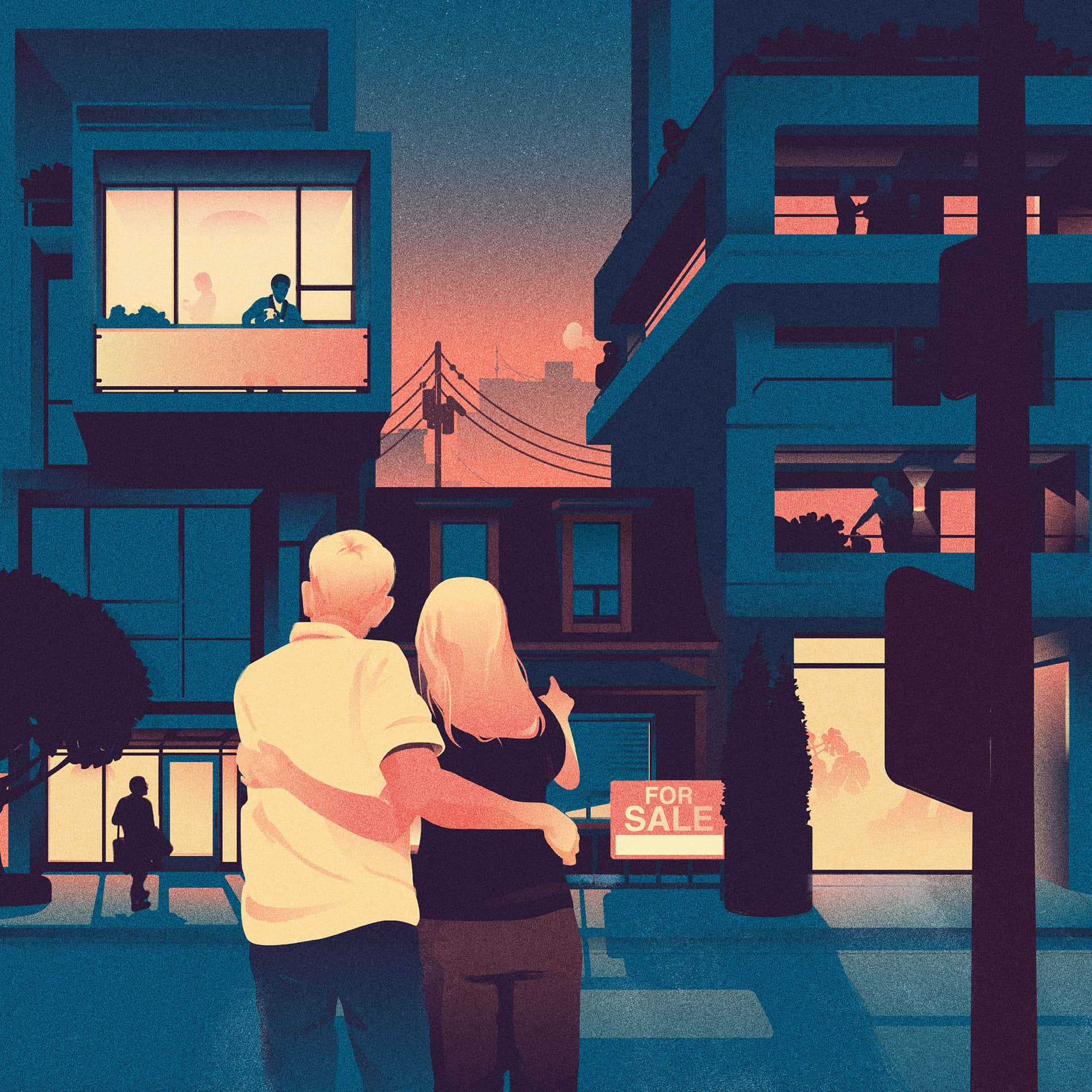

This Is Not Normal: A Letter From the Toronto Real-Estate Forever Boom

Money & the World

What’s Up With All Those Crypto Laser-Eyes Profile Pics? A Definitive Investigation

Money & the World

Dumb Questions For Smart People: Why Parenting Inequities Make Mothers Leave the Workforce

Money & the World

The problem seems to be how little we expect of the word “efficient,” as well as the many impoverished forms we will accept of the phrase “all available information.” For there is no telling how much rosy projection, willful denial, irrational exuberance and mass delusion might be moving markets on a daily basis. Should all information be suddenly, divinely revealed and the true worth of an efficient market established, its provisional valuations might fall like gold coins suspended in midair or skyrocket toward the redline as if on some carnie’s barometer.

The hypothesis is, at best, insufficient; at worst, a triumph of abstraction and academia. There is also this: most of us have at least a little taste for beating the market. Why not? You notice a pattern. You have a hunch. Soon, wise or not, a terrible itch sets in. Call it naiveté, or contrarianism, or arrogance: you place a bet, market wisdom be damned.

The New Man did not make the same impression on me as he had on Mother. His nervous laugh was cartoonish: it began like a mortar bomb and ended as sniper fire. He made wildly exaggerated claims. I disliked the two-toned way his toupee came together with his real hair. But Father was no alternative—Father was a bum, that much was well-established. If my thoughts returned to him as a source of wonder and longing, he was still a losing wager. His memory grew vaguer by the day.

If it felt funny calling the New Man “Dad,” which we did at Mother’s request, she assured us that “Dad” liked it. We were incorporating “Dad” into the fold, making him feel essential. It was Mother’s fervent wish to return us to the days of Mother, Father, Son, Daughter—only now with Little Brother, and a Father worthy of the name.

“Dad” was forced to demonstrate for us the pleasures of swimming in that sad canal. Sister and I did not dare approach it. As he waded in, we expected him to turn evil, as supervillains do when they fall into a toxic vat, or to boil alive. He did neither. He went under, came up spouting water. Did the backstroke in one direction. Did the breaststroke in the other. It appeared “Dad” might be auditioning for a position on a synchronized swim team. We looked on from dry land as the vegetation thrummed with insect life and the strong sun beat down. At some point, Mother acquired a preoccupied air. She stepped to the water line.

“Danny, what is that swimming next to you there? … and there? … and behind you, too? What is all that?”

“What … this?”

He lifted the thing in question out of the water.

“Is that a … what do they call that … a jellyfish?”

For reasons beyond my marine understanding, in that canal at that time of day a great quantity of bobbing, stinging, gelatinous jellyfish drifted down to our lonely end, where they congregated as if for a convention. Danny hurried out of the water, but it was too late. He didn’t turn evil, but he was badly inflamed and stank of vinegar, a home remedy, for the next two weeks.

♦︎

Soon after he swam with the jellyfish, “Dad” had another bright idea. He would take the family on a tropical tour in a glass-bottom boat. I was thrilled. Sister was, too. All the colour and clever locomotion of a frightening and formidable ocean life I did not care to encounter in the flesh would be peeled back for inspection by the likes of Sister and me. Little Brother, too, though Little Brother was hardly a year old.

We boarded at nine. The ship filled with diesel fumes as soon as we departed the decaying dock. I expected an open sea to disperse them. Finding themselves so far from shore, however, the sickening fumes only seemed to hug the boat tighter. And the ocean made matters worse by adding swells and a mean current.

The glass bottom did not provide the perfect vision of a technicolour seabed as promised on dry land. In reality it was a cloudy plexiglass cracked around the screw holes, difficult to peer into let alone penetrate amid the slosh and gloom. Sister and I lasted all of five minutes down there. I can still vaguely recall some swaying sea grass; Sister remembers the dead coral. We arrived back on deck in time to witness Mother’s reaction to “Dad”’s news that our little tour was four hours long. We’d been at sea forty minutes. Wee Little Brother was quite green by then. Sister and I were not far behind him. “Dad” seemed to know very little on the subject of boat tours, or children, or commonsense. Mother, it became clear, knew little on the subject of “Dad.”

♦︎

The efficient-market hypothesis is helpless to explain Warren Buffett. Or George Soros. Or Jim Simon, or Peter Lynch, or Michael Steinhardt. The hypothesis would like to suggest that these are the very players who make it efficient, but this is bogus post-hoc reasoning: winning investors of this caliber consistently locate and exploit inefficiencies in the market and then wait for the market to catch up to them.

Yet Warren Buffett himself concedes the practical wisdom drawn from the hypothesis: it is the rare bird who beats the market. The nonprofessional investor would be wise to assume an efficient market and throw in with it, because you never know what more it might know. This is the investing equivalent of experiencing the world as a child, and why investing money is so overwhelming for so many: the market renders us children all over again.

I kept trying to throw in with the market, my mother, but I also kept locating hype, bloat, misleading statements—accounting irregularities, if you will. Had she noticed New Guy’s temper? His lack of patience and appetite for drink? His poor judgment? His willful ignorance, his racism? His dismissal of facts in favour of hunches? His aloofness, which was not to be outdone by his taste for getting up close and personal by grabbing hold of my collar and tossing me against a wall?

One with clear vision can see many things and still be forced to wait for an efficient market to catch on.

By then, Father had called. A new chapter in his life had begun, and he wanted Sister and me to be the first to know. I had so effectively put him behind us, confined him to the bin of lost causes, and Florida had proved so distant, so distracting, and special bonds were so hard to maintain in the abstract, especially when one half of that bond was as young as I was, that I thought of him more like an uncle than I did a dad … or really just some random dude, if I’m being honest. In fact, I went so far as to lodge a complaint against “Dad,” who was not my dad, to Father, who was.

“‘Dad’?” he said.

“Yeah, you know … Mom’s new husband.”

“Why did you just call him ‘Dad’?”

I sensed the enormity of my error, the monumental effort she had put forth to erase the past.

“Because she asked us to,” I said.

“But Josh,” he said, “I’m your dad.”

With that basic fact affirmed, and my eyes full of tears, Father broke the fairy spell, and all the past came flooding back: the care he took to tuck me in at night, the bedtime stories he had read on repeat, the way he remembered to shut the blind so monsters would not peer in at me. There was also his smile, his patience, the size of his big hands compared to mine. At the same time that the past reasserted itself, all the discontinuities of my young life, from the divorce and its string of detonations to the move down to Florida to the disinformation campaign against Father in favour of the New Man, his rechristening as “Dad” and the whitewashing of a past full of games and pet names and hoary old customs—all the discontinuities that a young child might easily adjust to, confusing them for the ordinary course of family life, finally moved the ground beneath my feet, and I felt sick. I had betrayed Father. I had traded him.

He informed me on that first call that he had moved to Chicago, where he had been accepted into a training program for stockbrokers. Now he worked for Dean Witter Reynolds selling and buying stocks and bonds, and earning commissions with every sale. He promised to send me a book on the subject. I didn’t ask him about the child support that day. I got off the phone just happy to have heard from him, and that night brought news of his change of fortune to Mother. She wasn’t buying it.

“I know you love your father,” she said, “and you should, he’s your dad.” This was a concession I never expected to hear again. “But I have news for you,” she added. “He is a con man.”

“He is not a con man.”

“Then where is my child support?” she demanded. “If he’s a big fat stockbroker in Chicago all of a sudden, why has he not paid any of the money the court says he owes me? And that I could use!”

“He is not a con man,” I said, a little less certain than before.

She let the claim dangle. “We’ll see,” she said.

There it was: the wager. As the market, Mother knew so much more than I did. She had all the adult stuff down cold and acted accordingly. I was just a kid harbouring some dumb hope. But I also knew, in my bones I knew, that Mother had made a bad bet on New Man. She was thrice divorced and needed him to halt a slide, but she was just another “deluded investor with false hopes of easy gains.”

There are two things that determine the value of a public company on any given day: the story people tell about it, and the bottom line. The efficient-market hypothesis is full of holes in part because it’s perpetually imposing a premature ending on a story ever in progress. When the bottom line is announced by means, say, of a quarterly earnings report, the story being told—by the media, day traders and broker-dealers—had better align with the numbers. Otherwise the narratives diverge and the bleeding begins.

I have been telling you a story. I knew early on that the New Man, that Enron of men, would not pan out. But the New Man’s failure to be the end-all, be-all of Mother’s last-ditch romantic dreams did not affect one way or the other Father’s fortunes or his fate. The narrative act might make their fates appear intertwined—if the one is up, the other must be down—but nothing could be further from the truth. Father had called, he had declared certain things, but the bottom line remained an open question. To Mother, he was spinning a good yarn about second acts. She demanded to see the money before she would swallow the story. Frauds, you see, take random walks, too—usually right over cliffs.

Whenever I read about the efficient-market hypothesis, which provides the theoretical basis for passive investing, low-cost index funds and a lot of sound practical advice for the everyday investor, I’m put in mind of Churchill’s assessment of democracy: “No one pretends that democracy is perfect or all-wise. Indeed it has been said that democracy is the worst form of Government except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time …”

An efficient market is the triumph of hope over common sense, a sleight of hand and trick of time, a possible tautology, and an intellectual compromise, but no one can doubt its usefulness or unlikely wisdom: diversify broadly and hold for the long term. It’s the worst theory imaginable, with the exception of all the rest of them.

When Father sent me “Understanding Wall Street” in the mail, (“To Josh, Much Love, Dad”) I went straight to the chapter called “Investing and Trading,” where I found a description of “The Stockbroker”: “The Stockbroker is most likely a graduate of an extensive training course and has passed a comprehensive test prepared by the New York Stock Exchange and the National Association of Securities Dealers before being approved by the Securities and Exchange Commission.” It seemed very unlikely that Father could have done all that. He couldn’t even hold on to the company car.

At the same time, however, I knew he was a better man than New Man, and I had to put my money somewhere. I was already a contrarian, and I saw a pattern that Mother refused to see. I wanted to believe that she had sold Father at his lowest and bought New Man way too high, without doing any due diligence, and then holding on as one might have Eastman Kodak, or Polaroid, or Pets dot com. Had she just held on to the earlier issue, trusting in the true value of his underlying character (or so I chose to believe), despite the random walks he took in search of himself, which she mistook for a nosedive, she might have realized richer returns than she did trading him for a man who was his spiritual and intellectual lesser, a self-deluded bigot and drunk, and now a penny stock in someone else’s portfolio.

♦︎

The storm that seized Cudjoe Key on the day I asked Father about his child support passed, and the days brightened. I spent them riding my bike up and down Spanish Main, fishing in canals with shrimp bait, and catching chameleons running along the stucco walls. I felt more grounded with Father’s voice in my ear again, but I still couldn’t say I wasn’t holding on to a pipe dream of my own—until I returned to the house on Snapper Lane and found another letter in the mailbox.

He made that check out to Mother, but he sent it to me. He wanted me to see with my own eyes how the bottom line supported the story he was telling. It was real money, too, for it included not just that month’s child support, but all of the back pay she was owed, as well. I presented it to her the minute she came home from work, and the market moved.

Joshua Ferris is the author of three previous novels, “Then We Came to the End,” “The Unnamed” and “To Rise Again at a Decent Hour,” and a collection of stories, “The Dinner Party.” He was a finalist for the National Book Award, winner of the Barnes and Noble Discover Award and the PEN/Hemingway Award, and was named one of The New Yorker’s “20 Under 40” writers in 2010. “To Rise Again at a Decent Hour” won the Dylan Thomas Prize and was shortlisted for the Booker Prize. His short stories have appeared in The New Yorker, Granta, and Best American Short Stories. He lives in New York.