Money & the World

The Long-Term Economic Disaster of Cash Bail

We spoke to Robin Steinberg of The Bail Project and Colin Doyle from the Criminal Justice Policy Program at Harvard Law School about how the cash bail system fuels and funds mass incarceration — and how it wreaks havoc on society.

Wealthsimple makes powerful financial tools to help you grow and manage your money. Learn more

As the protests over George Floyd’s killing by police broadened into a reckoning with systemic racism, a spotlight has been trained on America’s problematic cash bail system. And an idea that had been percolating for quite some time became paramount: the American cash bail system acts like a regressive tax, causes economic disaster, and fuels the extraordinary rate of incarceration in the country.

Wealthsimple spoke to two leading activists in the bail-reform movement: Robin Steinberg, CEO of The Bail Project, and Colin Doyle, a staff attorney with the Criminal Justice Policy Program at Harvard Law School.

*The interviews were conducted separately and we have edited them and compiled them into a single conversation.

What was bail initially supposed to accomplish?

Robin Steinberg: Bail was created as a form of relief (from having to remain in jail until a trial). The theory was if you were charged with a crime, a judge would set bail in an amount that you could afford to pay. You would pay that bail as collateral, and that would create an incentive for you to return to court. That is the foundation of our American cash bail system.

And the theory was that if it was an amount you could pay, but it hurt, it took a bite out of your pocket, that you wouldn't skip town because you didn't want to lose it.

Steinberg: That's right. The theory was, it will provide the reason for you to come back. Of course, that assumes you wouldn't have come back without it, which is a whole other question we could talk about. But yes, it was meant to enable people to be free while they were fighting their case.

How does the bail lending system work? What does it mean to post bond?

Colin Doyle: The commercial bail bond industry is a unique United States phenomenon. There are only two countries in the world, the United States and the Philippines, that allow for-profit bail bond practices at all. There are a handful of U.S. states that don't allow commercial bail bonds, but most do. The process basically goes: if you can't afford the bond amount that the court has set, you can pay a fee to a bail bond company, and that company basically pledges the bond in your stead.

Steinberg: Most bail bondsman charge a fee of 10%. That's 10% of whatever the judge set as bail. So, if a judge sets a $5,000 bail, your family has to a pay a bail bondsman $500 in cash. You will not get that money back.

Sign up for our weekly non-boring newsletter about money, markets, and more.

By providing your email, you are consenting to receive communications from Wealthsimple Media Inc. Visit our Privacy Policy for more info, or contact us at privacy@wealthsimple.com or 80 Spadina Ave., Toronto, ON.

Doyle: If the charges are dropped, or if the person is acquitted, it doesn't matter: That fee is still owed. Whereas if you’re able to post bond yourself, you can eventually get that money back from the court if you show up and make all your court dates. If those families can't afford the bail bond, they can pledge their cars, or their houses, as collateral. They can also do installment plans with interest.

So, in a way, the bail lending system operates as a kind of penalty for not having money. I'm guessing the interest rate is not highly advantageous to the borrower.

Doyle: No. It winds up getting people trapped in cycles of debt. The big takeaway is that bail bonding winds up being a regressive tax on the poorest communities.

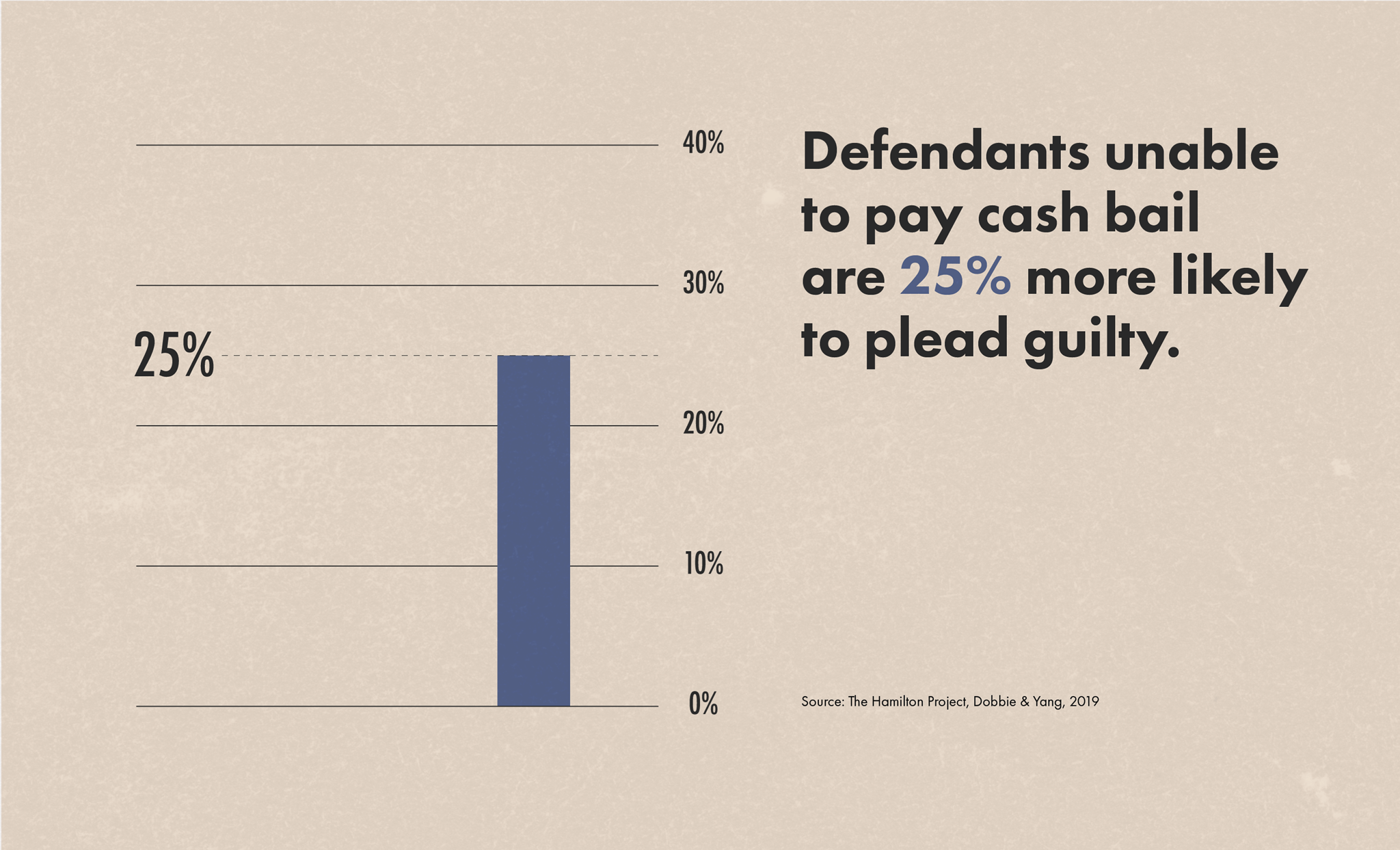

Steinberg: It's important to remember that if you're in this situation and you're from a low-income family, you are making decisions about whether to feed your kids, pay your rent, or pay a bail bondsman to get you out and get you back home. It really puts people in an untenable position. And what winds up happening is that the overwhelming majority of people just plead guilty to go home. The judges and prosecutors will make them an offer, and they go, "OK, whether I did the crime or didn't do the crime, at least I'll get home to the safety of my family and I can kiss my kids goodnight."

Jail, whether you are there for two days or two months or two years, is a scary, dehumanizing, terrifying, violent place. In a jail cell you are subjected to physical violence, sexual violence, your mental health suffers, your physical health suffers. The conditions you are living in are often inhumane. Meanwhile, being in jail has these devastating consequences on your life. You can get evicted from your home. You can lose your job. You can get thrown out of school. Your immigration might be jeopardized. You might even lose custody of your children. So, while you are sitting in this jail cell experiencing these horribly traumatic consequences to yourself, your family and your life is falling apart on the outside. It's always funny to me when people say, "Who would plead guilty to something they didn't do?" And I say, "Spend a day in a jail cell and you’ll see how easy it would be to plead guilty to something that you didn't do."

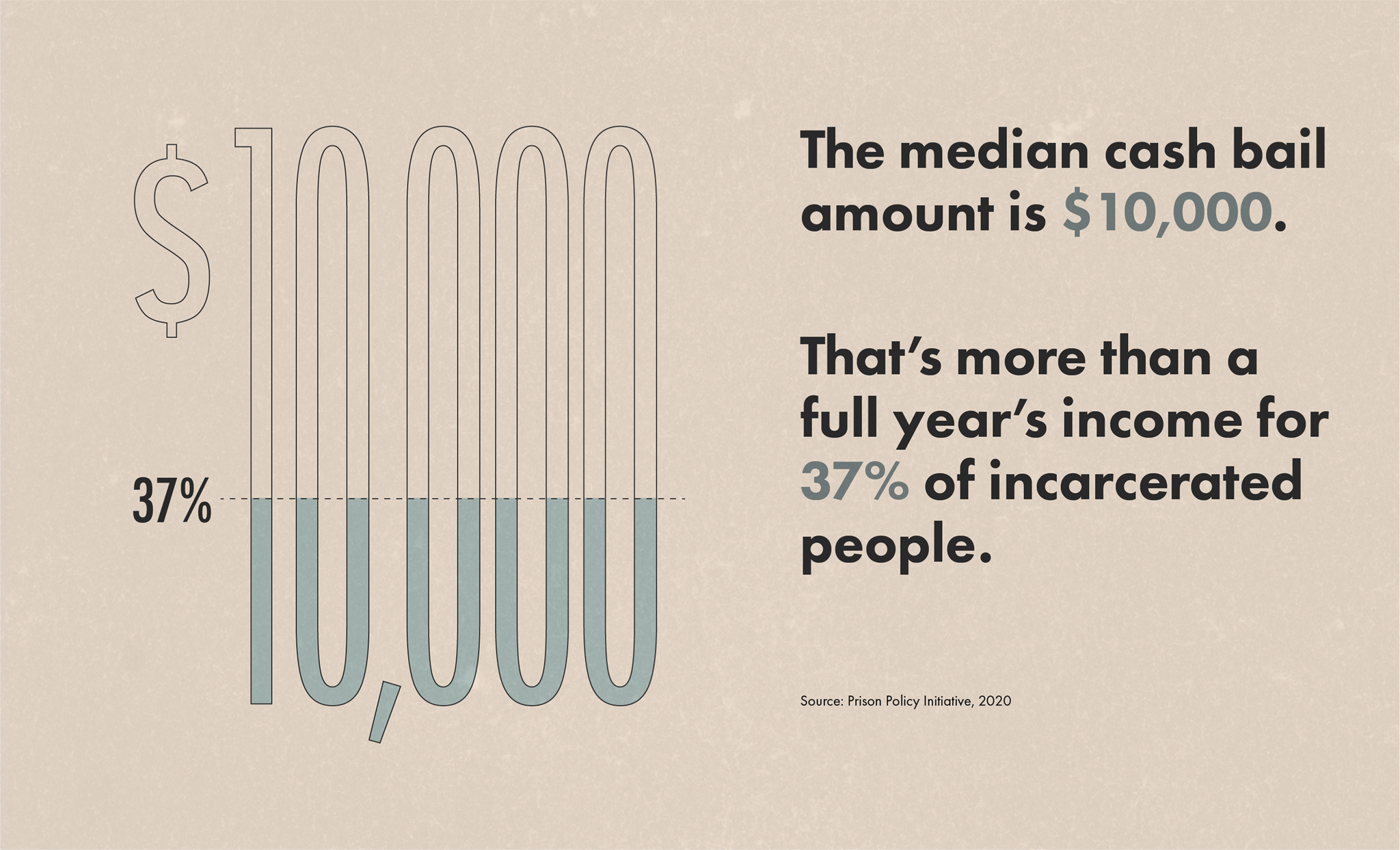

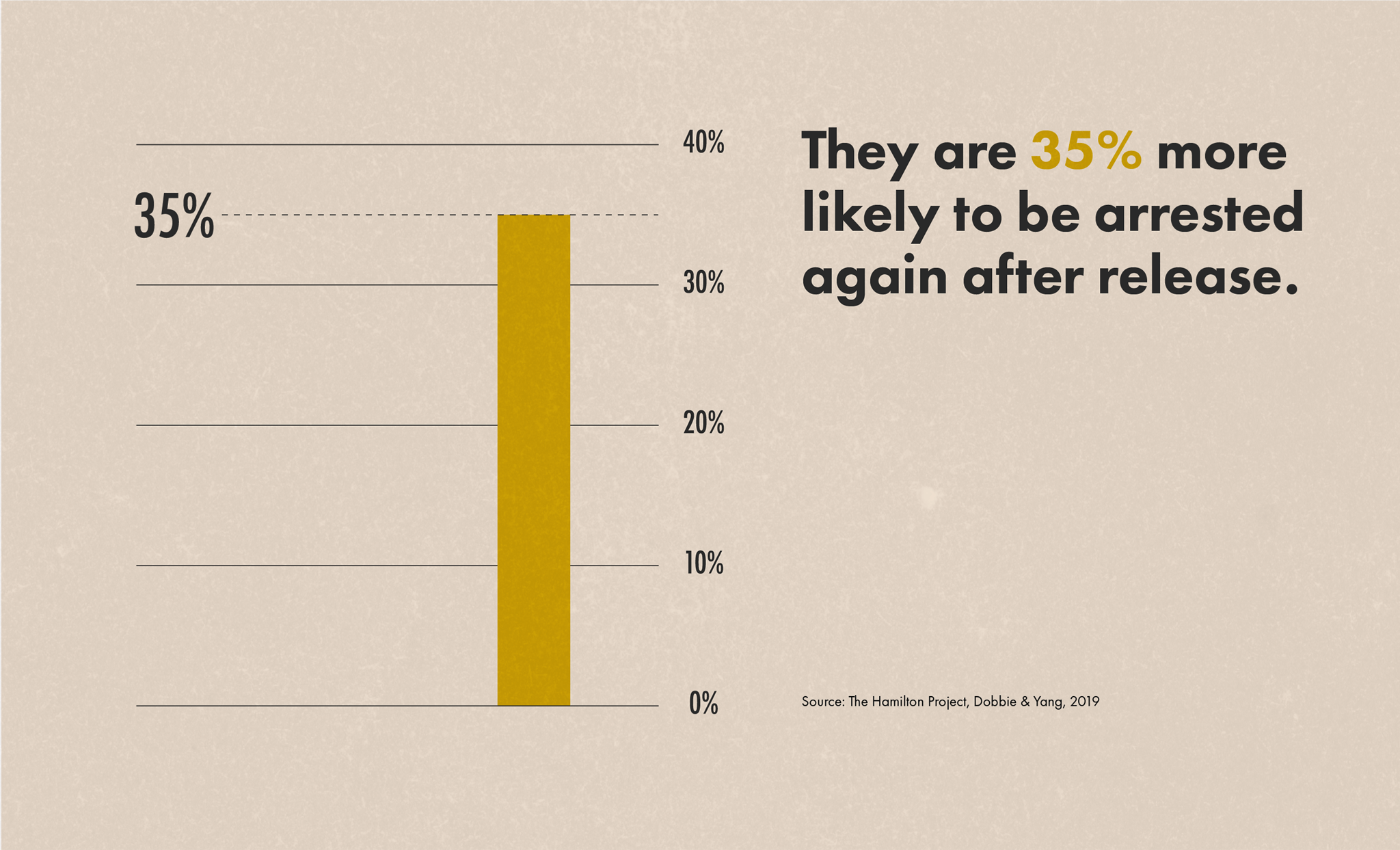

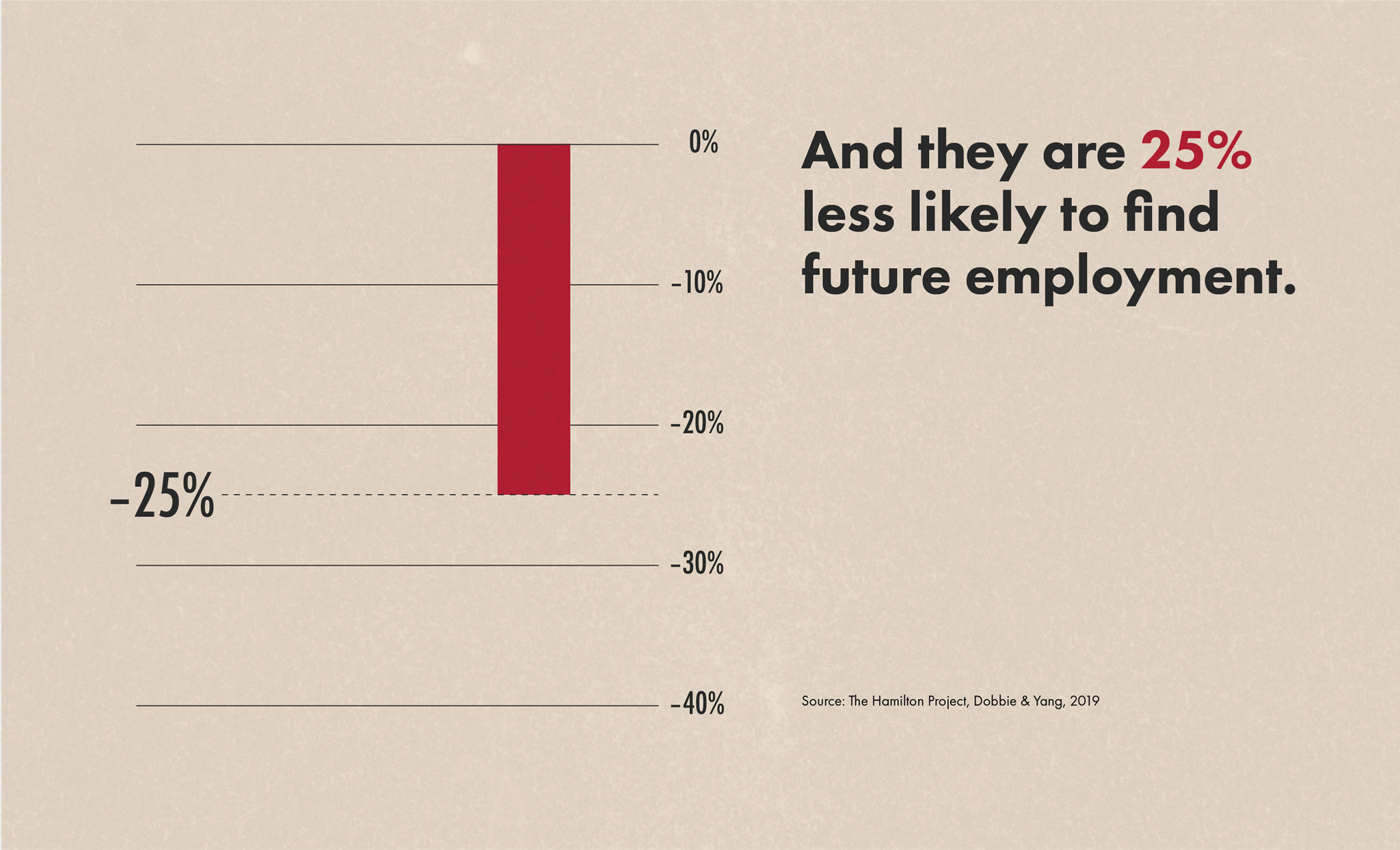

The cost of bail in three charts

Controlling for other factors, cash bail makes it more likely for defendants to become ensnared in the criminal justice system and curtails their economic future.

On a typical day in the American justice system, how many people are in jail waiting for a bail hearing — or if they can’t afford bail, are just stuck there until their trial?

Doyle: On any given day, just under half a million people are in some form of pretrial incarceration. They’re in jail, waiting the disposition of their case. To put that number in context, that's more people than we had all together in our jails and prisons in 1980 — convicted and unconvicted people combined. The average stay in jail in the United States is about three weeks. That means that about 11 to 15 million people get processed through the system in any given year.

So, option 1 is pay your own bail. Option 2 is a bail bond. Can you talk a little bit about option 3 and how that fits into the issue of bail reform?

Doyle: Option three is you wait in jail for the case to be over, right? For someone who is innocent, who can’t afford bail, and who doesn't want to plea out, who wants to be vindicated, this can cost them a lot in terms of time. The classic case is the case of Kalief Browder, a teenager in New York City who had been accused of assaulting a guy and stealing his backpack which had money in it. Browder maintained his innocence, and he was kept in jail on Rikers Island for three years until eventually the prosecutors dropped the case. He missed most of high school. He refused to take a plea that was offered multiple times because he was innocent. And he became the kind of poster child for the problems with the bail system. He endured horrific conditions at Rikers including beatings by other inmates and beatings by guards. He kind of became the face of the need for bail reform, and The New Yorker did a profile about him. Then he ended up taking his own life a few years later. He has become this example of the harms the bail system can impose, including on people who maintain their innocence.

What about the folks who post bond through a commercial bail bond company? Do we have a sense of the economic impact of those on poor communities? How much they extract from poor communities every year?

Doyle: Let’s look at Los Angeles as an example. In Los Angeles, between 2012 and 2016, $193 million in nonrefundable bail bond deposits were made to bail bond agents. Of those, Latinos paid $92 million, African-Americans paid $40.7 million, and whites paid $37.9 million. It’s not usually the person accused of the crime who's paying this. It's the broader community from which they come: their families, their wives, mothers, girlfriends, husbands. This follows a much broader trend in American criminal law in recent decades. We've used our court systems as a regressive tax on poor communities. Courts have increasingly relied on things like fines and fees to fund basic operational costs. Regardless of guilt or innocence, and without any sense of proportionality, our criminal courts are revenue generating machines that take money from poor communities.

Recommended for you

The World Is on Fire. Yet Life Is ... Getting Better?

Money & the World

Tariffs Are Here. How Ugly Could This Get for Canada?

Money & the World

The Most Compelling, Surprising, and Delightful Ideas of 2025

Money & the World

Prediction Markets Are, Suddenly, Everywhere. Wall Street Wants In

Money & the World

What are community bail funds, and how and why did they begin to emerge?

Doyle: The original bail funds started during the civil rights movement, as people were being arrested at protests and demonstrations. It was a way to pool money together and bail people out of jail; if you were arrested for civil disobedience, the community funds would be able to post that money to bond you out, you'd make your hearings, and that money would be returned back to the fund. This is part of why bail funds work: the money cycles through. When somebody donates a dollar to a bail fund, that one dollar doesn't just go to help one person get bailed out. When that person gets bailed out and then returns for their court date, that money — or at least most of that money — returns to the bail fund, which then uses that same dollar again, and again, and again, to continue the work.

Robin, you started The Bronx Freedom Fund in 2007. There had been bail funds before, but not with that sort of broad, widespread focus. Is that correct?

Steinberg: Yeah. What I found in my research was that most bail funds had been created in response to a political moment: the civil rights movement, or for a labor union fund to bail people out during protests as well. Targeted bail funds. And of course, look, people from low-income communities and Black and brown communities around this country have been pooling their resources and trying to get their loved ones out for as long as bail has been a thing, right? But yes, the Bronx Freedom Fund was the first revolving bail fund of its kind that I'm aware of. We created it with one grant and we really thought about how if bail comes back at the end of a criminal case and we provide the kind of supports the clients need to make sure they get back to court, the money should be able to revolve in a fund and we should be able to use that $1 over and over and over again to bail out more people. But of course, when we had the idea in 2005 and started the revolving bail fund, we had no idea whether people would come back to court.

Right. So if the idea of bail is that it’s the thing that makes people come back to court, what happens if you take that incentive away? That was the question no one had answered?

Steinberg: Exactly. We believed that people would come back to court. And as it turned out, 95% of our clients come back for all their court dates.

Over 10 years of tracking that data, we were able to not only smash the myth about cash bail being the thing that makes people come back to court, but we were also able to see what the downstream impacts were. We watched over half the cases get dismissed; we watched clients who were out jail and able to fight their case from a position of freedom. And even when they decided to plead guilty, the sentence that the system then handed out rarely involved jail time. It was almost always tied to community supervision, probation, restitution, community service.

And what you began to see was once you remove that coercive lever of bail and the ability to force somebody into a plea bargain, systems will actually respond by trying to be more creative about what justice might look like, what just sentencing could look like. The system stopped relying on what I call the dumb blunt instrument of jail, which was the default as a sentence when you are in a jail cell.

Cash bail has been the driver of mass incarceration in this country for decades now. It is responsible for 99% of jail growth in this country over the past 25 years and it is not an exaggeration to say that cash bail is the oil that keeps the criminal system running. Without it the system would come to a crashing halt. You could not possibly arrest the numbers of people that are arrested and brought into the system and adjudicate every single case. So, it has allowed all sorts of horrific things to happen and twisted our criminal legal system in a way that has made it ripe with injustice and racial disparities and unconscionable treatment of people.

In the long term, is the ambition to arrive at a place where there are sufficient bail funds to cover everyone, or is it really about making bail funds obsolete—to use the high appearance rate as proof that the whole idea behind bail was wrong in the first place.

Steinberg: The goal of The Bail Project [the present-day descendent of the Bronx Freedom Fund] is to put ourselves out of business one site at a time. Nothing would make us happier. Every single person who works on this staff across this country is committed to the goal of putting ourselves out of business and throwing a huge shutdown party. And that is because that would mean we had been successful at the other part of our organization, which is not just bailing people out and keeping the data but actually using that knowledge and that data to inform politicians and local elected officials and policy makers and judges to move systemic reform forward and eliminate cash bail so that bail funds are no longer needed.

Now that there is finally this focus on the systemic problems in criminal justice, in particular the discussion of defunding or even abolishing police departments, should we regard bail reform as a component of that discussion? Or is it a completely separate track?

Steinberg: The way to analyze the criminal legal system is to look at it like a tapestry. You can pull any one thread and begin to disrupt and dismantle it. You can pull at the thread of cash bail and eliminate it and allow more people to be free and get them home. You can pull at the thread of jail conditions. You can pull at the thread of whether there should even be jails. You can pull at the thread of policing. It's all a tapestry of interwoven systems that all have to be reimagined in this new world that I hope will last — the legacy that I hope George Floyd's death has left behind for all of us.

I do think we're at a moment of reckoning. It is the most exciting, inspiring time, and heartbreaking time, that I can remember. And I've been around for quite a while now. People are finally stepping up and seeing the interconnectedness to other systems in this country that we have created that also have had devastating impacts on the Black community and on people of color in this country. I'm really hopeful.

Doyle: You've got people like Rand Paul and Kamala Harris talking about bond reform. You have states like New Jersey and California passing huge laws related to bail. I do think it's something in our present moment. The money bail system is closely tied to policing, because one of the big forms of unchecked police violence is the ability to send someone to jail on close to nothing at all.

Steinberg: Interestingly I think some of this conversation actually started with Covid-19, to pivot a little bit. Covid-19 hit and it started coming into jails and spreading like wildfire. You cannot socially distance, you don't have access to protective gear, you barely have access to health care in most jails. We have 3,000 local jails in this country. And so, we saw that coming, and we knew that systems needed to begin to de-carcerate quickly to avoid a catastrophe. It simply shouldn't be that poverty — not being able to pay your cash bail — turns into a death sentence because you are sitting in a jail cell as Covid-19 is coming your way. So, we worked with our systems partners and encouraged them to de-carcerate as many people as they could, as quickly as they could, as Covid-19 began to bear down on us. That was in March. And we began to see jurisdictions release hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of people across the country. Which began to get people having the conversation. If we can do this when there's a health crisis, why couldn't we have done this all along?

Wealthsimple's education team is made up of writers and financial experts dedicated to making the world of finance easy to understand and not-at-all boring to read.