Money Diaries

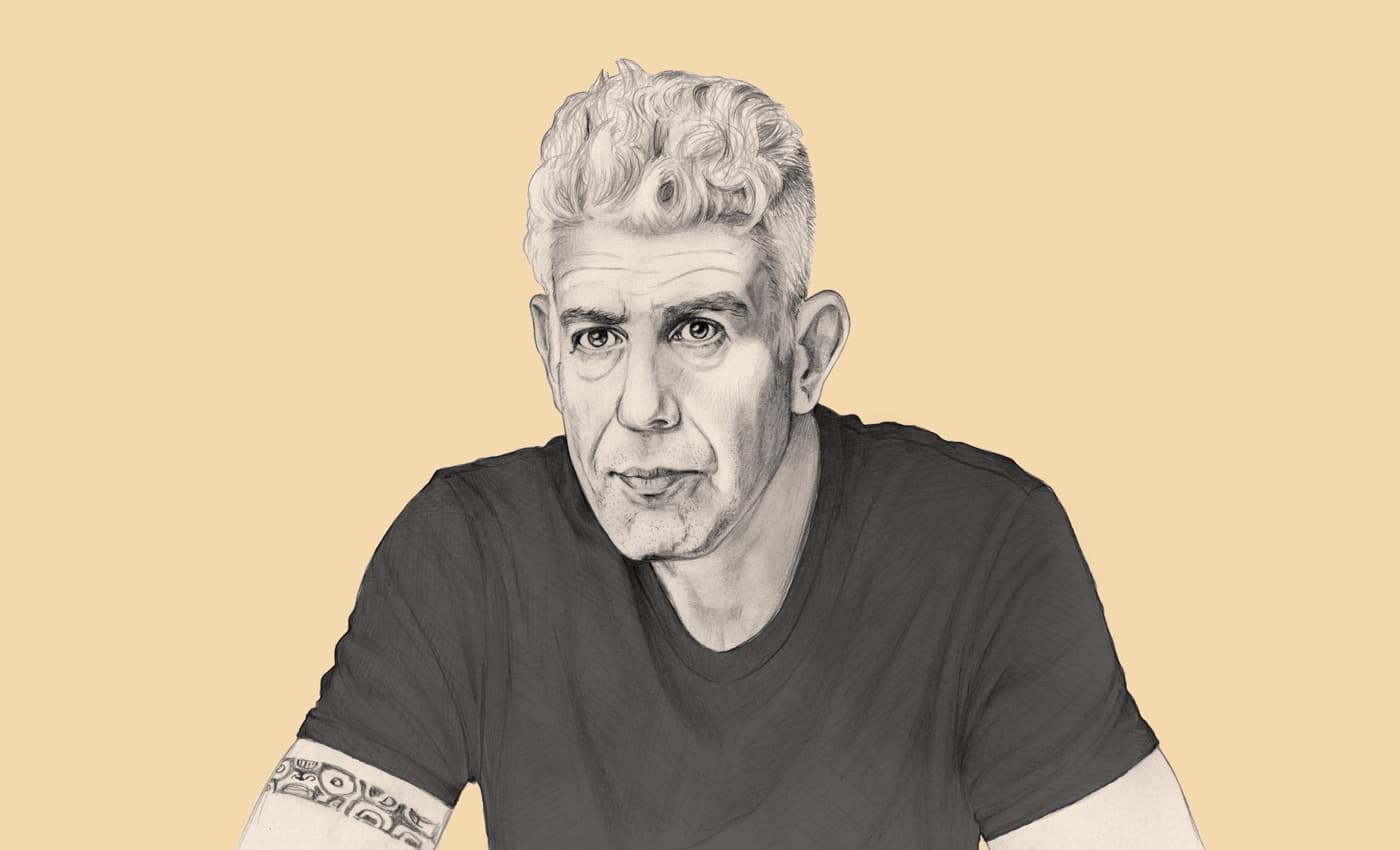

The Warby Parker CEO Thinks You Should Give Your Money Away. Now.

You can trace the ethos of Neil Blumenthal's company, and his commitment to extraordinary charity, to a town in El Salvador.

Wealthsimple makes powerful financial tools to help you grow and manage your money. Learn more

Wealthsimple is a whole new kind of investing service. This is the latest installment of our recurring series “Money Diaries” where we ask interesting people to open up about the role money has played in their lives.

I grew up in New York City in an upper middle class family. My mom was a registered nurse for 30 years, and my dad was an international tax consultant. In an indirect way, my father’s profession ended up having an outsize influence on how I live my life, financially and philosophically.

My father had a client named Chuck Feeney, who is one of the most generous and influential human beings the majority of the world does not know about. My dad would tell me about him constantly. Through his organization, Atlantic Philanthropies, Feeney radically reshaped global philanthropy. What interested me about him perhaps more than anything else was that he committed to donating his wealth while he was alive. He wasn’t going to create trusts and foundations that would give bits and pieces over years. He believed that change made today has a bigger impact than change made in the future because urgent challenges need immediate action. It was his example that basically created the giving pledge. Feeney really shaped my perception that there's no time like the present.

Sign up for our weekly non-boring newsletter about money, markets, and more.

By providing your email, you are consenting to receive communications from Wealthsimple Media Inc. Visit our Privacy Policy for more info, or contact us at privacy@wealthsimple.com or 80 Spadina Ave., Toronto, ON.

Both of my grandfathers were entrepreneurs. One had a store on the Lower East Side that sold bedding, and the other would buy excess textiles from mills in the South and then sell them to department stores in the New York area. Maybe they had something to do with how I became an entrepreneur, but it was something I was always interested in. When I was a kid, I started a dried fruit stand after watching an infomercial for a food dehydrator. You know, infomercials can be pretty compelling — “You can make dried fruit! You can change grapes to raisins and make apple and banana chips!” I was like, “Oh, man, I like all those things, and I know that other people do, too!” Of course, when I got the actual food dehydrator, it was really crappy quality — a few trays of plastic and a small heat coil and fan on the bottom. I'd plug it in, and it'd take literally two days to dry the fruit. In the end, it was way more expensive for me to do it myself than to just buy dried fruit. That was a failed business.

When I was younger, I definitely thought that I was going to be a foreign policy person. I went to Tufts University, which is known for international relations. I took the foreign service exam because I wanted to work at the State Department, and while I got to the final round, which is pretty rare for people without work experience, I ultimately didn't get in.

Back in New York I met a guy named Jordan Kassalow, an optometrist and the founder of a not-for-profit called VisionSpring. He explained that there are almost a billion people in the world who need glasses but don't have access to them. His solution was to train low-income women to start their own businesses giving vision tests and selling glasses to people in their communities. This was kind of a wow moment for me. You see, in the health-care hierarchy, things like infectious disease and clean water are always going to get more funding than something like eye care. But eye glasses are a tool that help people work, that help people make more money. So it’s something that people would and could spend money on. And by training people to start their own businesses, you have this economic incentive to do it over the long run. Kassalow ended up inviting me to move down to El Salvador to work on the pilot program. He offered to pay me a stipend that would cover my living expenses. It wasn't overly compelling from a financial standpoint, but I was really excited to be doing impactful work.

There are certain human traits that are universal, and one of them is dignity.

Recommended for you

VisionSpring was just getting set up in Santa Ana, in El Salvador. It had identified a partner, a nonprofit microfinance organization that also had an eye clinic. I basically lived inside the eye clinic, in this giant room that had 20 beds where people could stay if they needed to travel from rural areas to have cataract surgery. As part of my job, I would go into rural communities, meet with women, and train them to give a vision test and sell glasses. Nobody had done this before, so there was no one to learn from. I started observing and listening. One of the problems we had to solve was that people need to want to wear the glasses. So we found out what they liked. We looked to see the type of glasses that seemed popular in their community, the styles, colors, and materials. What that experience really drove home for me is that all people are equal. There are certain human traits that are universal, and one of them is dignity. Whether they’re rich or poor, people want to work, they want to get paid for a hard day's work, and they want to buy things themselves. Just as a person on Madison Avenue wouldn't want to wear an ugly pair of glasses, somebody in a rural area living on less than $4 per day also wouldn’t want to wear something they found ugly or ridiculous.

We designed the frames to suit the market, and we priced them according to what people could afford. We needed to price them in a way that achieved two things. One, the people selling them would make money; and two, people could still afford to buy them. For a lot of these folks, once they got their glasses, their productivity would increase by 35%, so they would make that money back in about a week.

When we made our business plan for what would become Warby Parker, we agreed on a commitment that for every pair of eyeglasses sold, we would distribute a pair to an individual in a developing country. And we ended up partnering with VisionSpring and other experts to distribute those glasses. We wanted to do that, rather than giving a percentage of revenue or profit, because all we cared about was that a human being was going to have the glasses they needed to be successful in life. We also worried that if there came a time when we were not in charge of the company anymore, somebody could manipulate the percentage of revenue or profit.

I tell people that everybody should find a way to donate some amount, no matter how small. Start now.

Today, we've provided glasses to more than 2 million people. We're currently partnering with the city of New York to reach even more. We have two approaches. In the first, the city provides eye exams to students. The child selects from between 12 different types of frames, we make the glasses, and the school issues them to the student. So we're covering the cost of the frames and lenses, and the city is covering the cost of the eye exam. We're doing that in 130 schools. We're also working with the crowd-sourcing platform donorschoose.org, where teachers tell us how many kids they have in their class, and we'll come in, bring an optometrist, do eye exams for those kids, and the kids who need glasses will pick out pairs they want.

I still give advice that goes back to Chuck Feeney in a way. I tell people that everybody should find a way to donate some amount, no matter how small. Start now. Even if it's $10 to $15 dollars. It builds muscle memory; it exposes you to organizations so when you do have the ability to contribute more, you might already have discovered who you want to give money to.

Is giving good for business? I actually think so. I've always found that working in organizations that are more mission-driven — where the impact is big — motivates me to do my best job every day. And that's enabled me to accumulate more wealth than I anticipated.

As told to J.J. McCorvey exclusively for Wealthsimple. Illustration by Jenny Mörtsell. We make smart investing simple and affordable.

Wealthsimple's education team is made up of writers and financial experts dedicated to making the world of finance easy to understand and not-at-all boring to read.