Money Diaries

How to Get Thrown Down a Flight of Stairs for $500

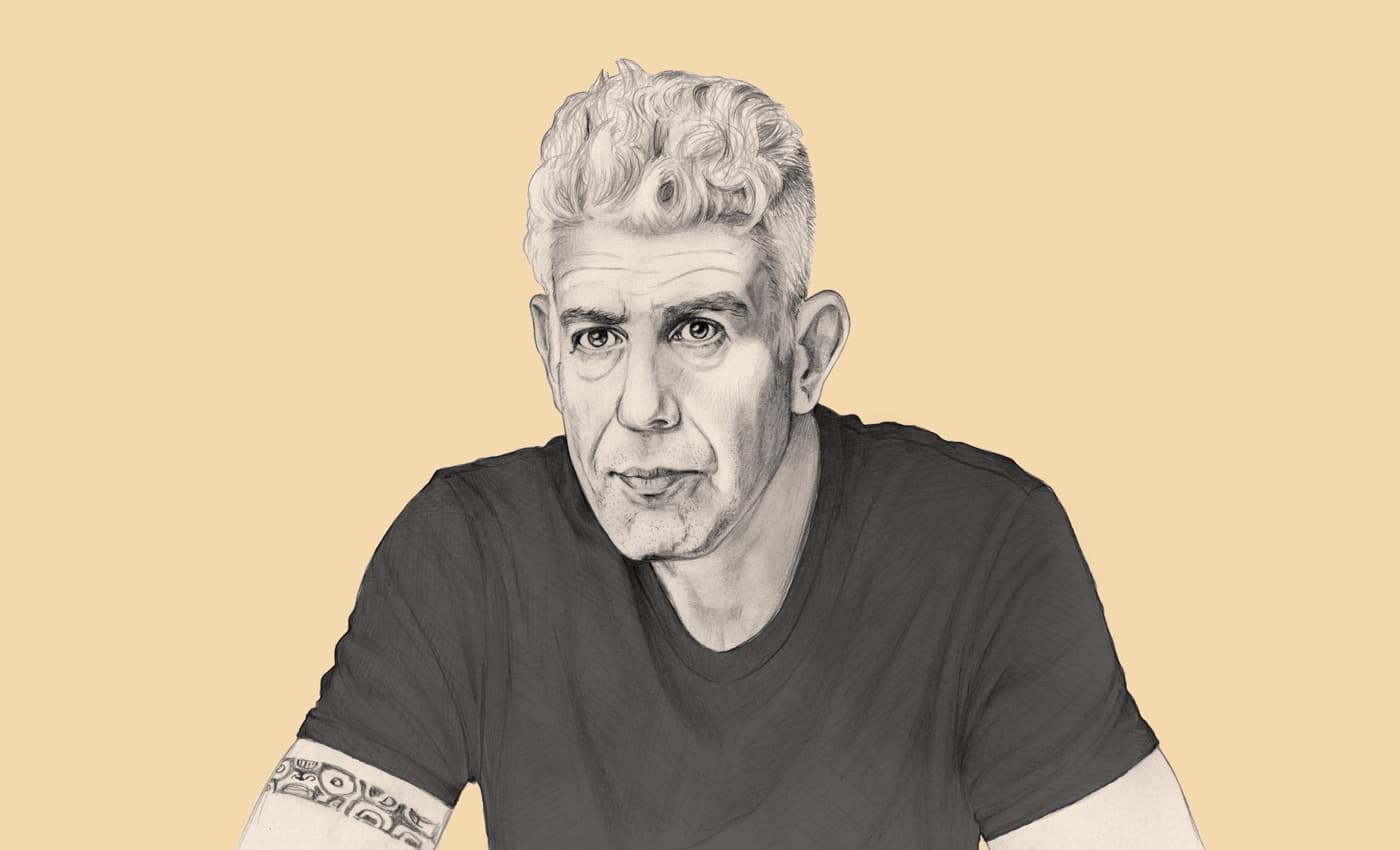

Nash Edgerton, the accomplished stuntman (The Matrix movies, Mission: Impossible II, Superman Returns), and newly minted director (FX's Mr Inbetween), on the economics of being a human punching bag.

Wealthsimple makes powerful financial tools to help you grow and manage your money. Learn more

Wealthsimple is an investing service that uses technology to put your money to work like the world’s smartest investors. In “Money Diaries,” we feature interesting people telling their financial life stories in their own words.

I was the type of kid who would do whatever stupid thing I could think of — jump off the roof; jump out of trees; line up my cousins and jump over them on my BMX bike. None of these ideas seemed stupid to me at the time. They all seemed awesome, even when things went badly.

I grew up an hour northwest of Sydney, Australia, in a town called Dural. My dad was a lawyer; my mom stayed at home and worked her ass off trying to keep my brother Joel and I out of trouble. My grade school was deep in the bush, but we dressed in fancy uniforms — a blazer, a shirt, and a tie. In fifth grade, a bunch of kids in my class found a giant steel hoop and kept rolling it down a steep hill. I said, “Hey, do you guys dare me to dive through it while it’s rolling down the hill?” And everyone’s like, “Yeah, yeah! Do it!” This wasn’t the first time I’d dared them to dare me to do something wild.

So, this steel hoop is barreling down the hillside, and I’m sprinting after it. It was only as I made my lunge and dove through the air that I saw a 6-inch nail sticking out from inside the hoop. It stabbed me in the back, like a marshmallow going onto a marshmallow stick, collected me, and continued rolling down the hill.

An aerial stunt for a James Bond film that requires leaping out of a moving airplane — that will earn top dollar.

At the bottom, I surveyed the damage. I’d been scratched up pretty good, but I knew I’d survive. Worse was the hole in my shirt and blazer, which had been really expensive. My parents had bought clothes that were too big for me so they wouldn’t need to keep replacing them every six months. Now I had to go home and try to explain ... what? That some kids at school had dared me to jump through a hoop and I’d trashed my uniform? Like a lot of my childhood stunts, more terrifying than the stunt itself was dealing with the aftermath. On my way home, I was filled with dread.

Sign up for our weekly non-boring newsletter about money, markets, and more.

By providing your email, you are consenting to receive communications from Wealthsimple Media Inc. Visit our Privacy Policy for more info, or contact us at privacy@wealthsimple.com or 80 Spadina Ave., Toronto, ON.

As you can imagine, my parents weren’t happy. Fortunately, my grandmother had a unique and clever solution. She neatly detached the pocket on the front of my uniform and sewed it on the back, to patch up the hole I had ripped. So for the next couple of years I was the kid at school with a pocket on my back. Some of the kids even called me “pocketback.” All in all, it was a reasonable form of punishment for a dumb daredevil.

It wasn’t until I turned 18 that I learned about professional stuntmen, and realized that my lifelong hobby of flinging my body into danger could actually become a career. But this was before the Internet, and I had no idea where to start. One day, I pulled out the phone book and looked up “stunts.” There was just one listing — an agency in Sydney for stuntmen. I called the number and told the woman who answered that I wanted to be a stuntman. She told me not to bother — she said becoming a professional stuntman was a nearly impossible dream.

In Terrence Malick’s

The next day, I drove to Sydney, found the office, and knocked on the door.

As it turned out, I wasn’t the first rambunctious, big-eyed kid to land on her doorstep, and her phone was always ringing with daredevil types who thought they were stronger, and braver, than the rest. But what I had that the others might not was total persistence. I called her, or stopped by the office, every single week. Finally, she got so sick of me calling her that she introduced me to a stunt coordinator, and I went to meet the guy on the set of a movie called Reckless Kelly — from the same director who had made Young Einstein. What I saw that day was intoxicating: Real stuntmen performing wild shootouts; guys blowing up cars. This was the real thing!

I talked to a few of the stunt guys and got their phone numbers. I started calling them to find out where they were training, and I’d hang out at the gym while they worked out and practiced gymnastics, acrobatics, and rappelling. Gradually, they began to teach me their trade — basically, an old-fashioned apprenticeship. They took me with them to set as a stunt assistant, and let me carry their bags in exchange for the chance to watch them at work. My chores were unexciting — if someone was doing a fall into a stack of boxes, I’d fold and stack the boxes. But I’d grown up loving action movies, and shows like The Dukes of Hazzard, and it was thrilling to suddenly be so close to the action.

While I was hanging out on film sets, making coffee for the stuntmen, my parents thought I was at university, studying electrical engineering. After a year of doing the bare minimum in school to pass my classes, I decided to postpone the next semester. It was an easy decision; the only hard part would be telling my parents. My mom cried for about three months straight. My dad was equally unimpressed. They had sent my brother and me to private school, and now I was ditching university because I wanted to throw myself down stairs and get hit by cars. It was the equivalent of shoving a nail through my education and sewing a pocket on the back of my life.

Recommended for you

How to Quit Your Job and Bike Around the World for $17,000

Money Diaries

She Was Living in a Shelter Six Years Ago. Now She’s the CEO of Her Own Beauty Company

Money Diaries

Alison Roman Is the Patron Saint of Home Cooking and Everyone’s at Home

Money Diaries

Anthony Bourdain Does Not Want to Owe Anybody Even a Single Dollar

Money Diaries

After paying my dues month after month, I got my first paid gig. It was a show called Police Rescue and the job was nothing too glamorous: I was playing a dead kid, lying in an uncomfortable position on a pile of rocks, halfway down a waterfall. At night. In winter. I just had to lie there dead in this waterfall for hours on end. I got paid $250. But I’d been making eight bucks an hour delivering pizza, and working at the local video store, so this felt like a windfall!

A successful stuntman can make anywhere from $1,000 to $15,000 in a day of work. The level of pay is a combination of the scale of the project, and also the amount of danger involved.

Over time, I did more little jobs like that — basically, the scraps that the stuntmen I’d befriended weren’t interested in. But then I got my first proper gig, as the stunt double for the white-coloured Power Ranger on the Power Rangers movie. This was real stunt work and involved genuine acrobatics. The pay may have been more than everything else I’d made, combined.

When you’re a stunt double, you’re getting paid to be on camera, like an actor would, and then you’re also getting paid for what’s known as stunt adjustment, which is basically danger money, or hazard pay. If you’re falling down stairs, getting set on fire, or crashing a car, you get a bonus on top of your daily rate. A successful stuntman can make anywhere from $1,000 to $15,000 in a day of work. The level of pay is a combination of the scale of the project, and also the amount of danger involved.

Fire stunts pay especially well. As you might expect, getting set on fire can be truly dangerous. Gunfights pay surprisingly little. So many precautions are taken when guns are involved that any real danger is minimized. The highest-paying gigs are those that really have a chance to fuck you up. For example, any very high falls can have an enormous risk factor. An aerial stunt for a James Bond film that requires leaping out of a moving airplane — that will earn top dollar.

I learned to investigate the details of a shoot before accepting the job. If you’re offered $500 to get thrown down a flight of stairs, you might very well agree to it. But if you’re going to get thrown down the stairs ten times until they get exactly the shot they’re looking for, $500 wouldn’t be very appealing. Now, if you’re the person who fucks up a take, you always do another take at no extra charge. But, if the cameraman misses the shot, or they want to try it again for some other reason, you want to make sure you’ll be paid. Another variable is the stunt coordinator. They all offer different rates, and some are more generous than others.

When things go right, stunt work can be incredibly enjoyable. I got to work on all of The Matrix films. That was special. I was part of the stunt team, preparing the stunts (we call it stunt-rigging). I was also in a bunch of the shoot-outs, and was the stunt double for the character of Mouse. Sometimes, as a stunt guy, you end up playing a number of characters — you might play the guy who gets killed, and also the guy who kills him. In Terrence Malick’s The Thin Red Line, I probably died about twenty times. With The Matrix, we knew the Wachowski Brothers had a grand plan, but it can be hard to conceive of what the finished film will look like when your job is just to get shot 50 times and die in spectacular fashion. It wasn’t until the cast-and-crew screening of the first Matrix film when I was like, “Oh! That’s what we were making!”

Over time, even while working as a stuntman, I was always keeping an eye on the director. While they weren’t putting themselves in physical danger, the tightrope they had to walk seemed thrilling and perilous in its own way — crafting a story and managing a team simultaneously. I knew it was a challenge I’d want to take on myself one day, and eventually I got a chance to do it — I directed films called The Square and Gringo, and a new TV series on FX called Mr Inbetween, an intimate look at the life of a hit man.

I don’t want to get used to flying first class, and then once that becomes the norm, to end up back in economy. I don’t need to acquire a taste for the high life!

Hit men interested me, in part, because their lives bear some similarities to stuntmen — your pay is scaled according to the danger involved in each job, and who is hiring you. Of course, it also depends who the person is that they want you to kill. Are they a cop, for example? If so, your fee will be much higher, because there is going to be a lot more heat on you after the job.

Years ago, my friend Scott Ryan — who wrote Mr Inbetween and stars as the hit man — met a famous criminal named Chopper Read. Chopper had written evocative books about his years as an enforcer in the Australian underworld; his writings and the conversations Scott had with him inspired Scott to create Mr Inbetween. Scott and I often talked about the interior lives of criminals. A hit man has an unusual job, but also has the same pedestrian concerns as any of us — romance, family, paying the bills. On our show, you see him doing his job, but also hanging out with his daughter, dealing with his ex-wife, looking after his unwell brother, and trying to date a woman he meets at the dog park.

As for me, money has never been a primary motivation. When I started working as a stuntman, I just wanted to do what interested me, and how much I got paid was incidental. Now that I’m directing, I still feel the same way — doing something that I love is the prize; the money is just a bonus. I probably shouldn’t admit this, but I love directing so much, I would do it whether I was getting paid or not. Any mundane job I’d want to be compensated for, since you’re spending your time doing something you’d rather not be doing. But making a movie or a TV show I love — that’s something I’d do for free. But now that I have two daughters, I pay a little more attention to money.

I think if you’ve got enough money to get by, things are good. What must feel wrenching is to be really rolling in dough, and then suddenly lose it all. Here’s the comparison I make: When I’m buying a flight, I buy the cheapest ticket and sit in the back of the plane. A couple of times, folks have offered to buy me tickets in business class. I’ve always said no. Because I don’t want to get used to flying first class, and then once that becomes the norm, to end up back in economy. I don’t need to acquire a taste for the high life! I started my career falling down stairs, getting hit by cars, and being set on fire just for the love of it. I want to choose jobs based on how much they excite me, and never because of a paycheque.

As told to Davy Rothbart exclusively for Wealthsimple; transcript edited and condensed for clarity. Illustration by Jenny Mörtsell.

Wealthsimple's education team is made up of writers and financial experts dedicated to making the world of finance easy to understand and not-at-all boring to read.