Money & the World

How Canada, and Much of the World, Got Stuck in a Land Trap

Real estate can help spur small-business growth. But, as the author Mike Bird explains, soaring home prices can also create major economic headaches.

Wealthsimple makes powerful financial tools to help you grow and manage your money. Learn more

If you’re a first-time homebuyer, it’s easy to feel as if the entire system is rigged against you. Housing prices keep rising, wages have stagnated, and new construction has proved maddeningly slow. How did housing in a place like Canada, with a small population and an abundance of land, reach crisis levels? Mike Bird, the Wall Street editor for The Economist and author of The Land Trap: A New History of the World’s Oldest Asset, has answers. We spoke with him recently by phone.

Let’s start broad: why is land unlike any other financial asset?

Every other asset in the world depreciates, rapidly or slowly. Houses fall down. Bridges collapse. Ideas become irrelevant. This isn’t true for land. There’s no innovative element to its value; instead, most of its value is maintained by economic activity happening around it. If you buy it and that activity continues, there’s no reason it can’t stay valuable.

Sign up for our weekly non-boring newsletter about money, markets, and more.

By providing your email, you are consenting to receive communications from Wealthsimple Media Inc. Visit our Privacy Policy for more info, or contact us at privacy@wealthsimple.com or 80 Spadina Ave., Toronto, ON.

So land appreciates, but it’s a nonproductive asset. Yet you make an interesting point in your book that land has, in some respects, helped to spur economic activity. Explain that.

A lot of what we think of as small-business lending in most of the world is actually mortgage lending. Loans are secured against an entrepreneur’s residence. In a world with no homeownership, it’s difficult to imagine the vast majority of small businesses having access to credit at all.

But there’s more to the story: your book argues that, in the long run, soaring land prices can damage an economy. How so?

If people can’t afford land, they often don’t have collateral to borrow capital. So an entrepreneur with a good idea may never get a chance to fund their business. Then, over time, as land prices soar higher, banks slowly become mortgage originators and do far, far less business lending because land is seen as safer. Then the corporate side atrophies.

Recommended for you

How to Consume and Discern Information in Our Slop-Infested World

Money & the World

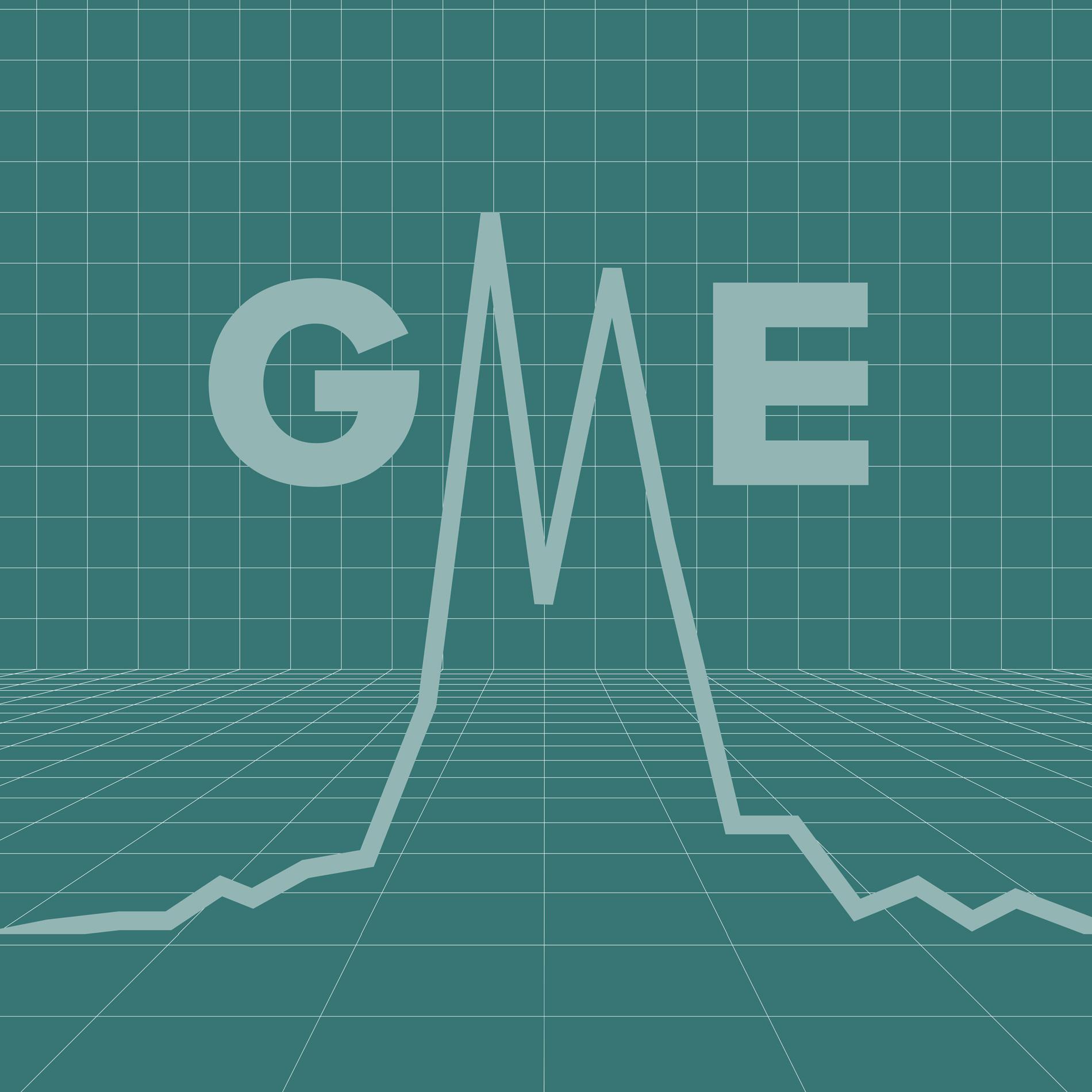

Data: Who Really Traded GME? Why? And What Happened to Them?

Money & the World

Tariffs Are Here. How Ugly Could This Get for Canada?

Money & the World

We Discovered the True Identity of the NFT Artist “Pak”

Money & the World

This is the thesis of your book: land is a trap because it often outcompetes other assets and sucks capital from more productive areas. This sounds like the Canadian story.

Right. The U.S. has a robust venture-capital and private-equity infrastructure, so young companies have a way to secure funding outside of banks. But in Canada, you don’t have as much of that.

In Canada and elsewhere, all sorts of policies and tax incentives make land an overly attractive investment. You propose ending such measures to alleviate the land trap. The trouble is that many ordinary people rely on their homes to finance their retirement. How do you end these policies without screwing them over?

There’s a huge merit argument for taxing land more extensively to discourage speculation and to make land a less attractive asset. But you can’t tell people for decades that homeownership is the path to security, as many governments have, and then turn around and say, “Now we’re going to rinse you for it.” These homeowners haven’t done anything wrong. This is why it’s really tough to reform land policies.

You write about how Singapore has avoided many aspects of the land trap. What did it do?

Singapore’s early leaders wanted businesses to thrive; they didn’t want all investment to flow to real estate. So the government bought about 90% of the land and provided quality, low-cost public housing to millions of citizens. If you’re a citizen, you buy a 99-year lease for a flat, and you can only buy one. And noncitizens are severely restricted from buying property. This approach caps prices, and it has helped Singapore build a low-tax, freewheeling free-market system that doesn’t disadvantage people or businesses.

This interview, which was edited for length and clarity, was conducted by Brennan Doherty.

Brennan Doherty is an education writer and researcher for Wealthsimple. His work has appeared in the Toronto Star, The Globe and Mail, TVO Today, MoneySense, BBC Business, and other publications.