Money & the World

We Can Fix the Housing Crisis! (Maybe! If We Follow These Steps!)

In just a few years, housing has gone from merely pricey to unattainably expensive for most Canadians. We asked policy experts how to make homes affordable again

Wealthsimple makes powerful financial tools to help you grow and manage your money. Learn more

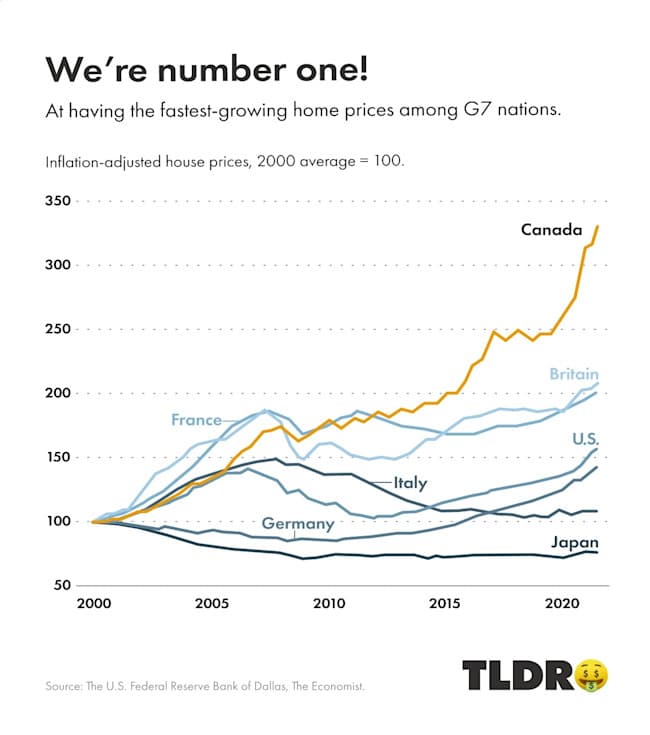

Canada’s housing market is, to use an academic term, a dumpster fire — at least for anyone renting or hoping to buy. (See the chart below, which shows the rise in home prices relative to other stuff.) The pandemic threw gasoline on the blaze, but the crisis had been growing for decades as Canada’s population swelled and not enough new construction went up. These days, according to RBC, just 45% of Canadians can afford a condo, down from 60% in 2019, while a mere 26% say they can afford a single-family home. And renting ain’t cheap either. The crisis has gotten so extreme that, according to one poll, 70% of Canadians — including homeowners, which is really saying something — would be happy or somewhat happy if home prices fell. The same poll shows that Canadians generally think building more homes would be the best way to cool off the market.

This quarter brought a lot of good economic news. But since painfully high housing costs are having such an outsized effect on people’s finances, we decided to dive deep into the topic. That meant talking to economists and poring through research about how Canada can improve housing affordability. Below, we unpack what we learned, and what a drop in home prices might mean for you. Keep scrolling.

So, how do we wake up from this housing nightmare?

The housing crisis has a lot to do with supply. According to some estimates, Canada needs to build anywhere from 5.8 million to almost 10 million new homes in the next 10 years to restore affordability. Which is, let’s say, an ambitious goal, given that a mere 235,000 new homes went up last year. Is it even possible to hit that goal? Housing experts generally point to three things that need to happen if we’re going to get close:

[1] Build up! And build denser! One of the biggest impediments to housing affordability in Canada can on the surface seem almost innocuous, if not downright wholesome: single-family homes. In 1916, the city of Berkeley, California, implemented the first single-family zoning rules in North America (for what were transparently hateful reasons). Canadian cities soon followed suit, passing ordinances that prohibited the construction of large apartment complexes in many neighbourhoods and thereby severely constricting the housing supply. Sixty percent of Calgary is still zoned exclusively for single-family homes.

Almost any policy expert will tell you that Canada cannot begin to address the housing crisis until it allows more medium-sized housing units (think townhomes and walk-ups, not necessarily giant towers) to be built in urban neighbourhoods. If that seems radical, consider that most European cities don’t have single-family zoning at all. Toronto, Ottawa, and a few other cities have already loosened zoning rules, but British Columbia has arguably made the most sweeping changes. Starting June 30, B.C. cities will automatically allow four- or six-unit complexes to be built on any lot that’s currently zoned for single-family homes. Other cities and provinces would need to adopt similar policies to meaningfully boost the housing supply, but B.C.’s zoning change alone could result in more than 130,000 multi-unit homes getting built over the next 10 years. As the map below shows, in Vancouver this new law could mean four times as many residences get built.

[2] Build smarter! Canada needs more apartments, full stop, but it also needs different types of apartments, especially ones that can accommodate families. (If cities are going to move away from single-family homes, families will need somewhere to live!) At last check, about 150 apartments in Halifax were available for rent on one listing site. But narrow the search parameters to “three-bedroom” and a grand total of two come up. This is partly because many apartments in Canada are made of wood (as opposed to concrete, as is common in Europe). So, fire codes require most apartment buildings over two storeys tall to have at least two stairwells, which wastes square footage and often pushes developers toward designing long, skinny, not-family-friendly units. Policy experts agree that the two-stairwell rule is outdated, since sprinkler systems have made apartment buildings a lot safer. If you drop the stairwell requirement to one in mid-rise buildings (which is also common in Europe), you can put more or bigger apartments on each plot of land.

[3] Spend money on houses, not homebuyers! Increasing supply is crucial to solving the housing crisis, but experts argue that cooling demand is just as critical. Canada used to build tons of public housing; in 1970, 25% of homes were non-market units (aka public or social housing). But in the ’90s, Ottawa defunded its public-housing programs, offloaded that responsibility to provinces and cities, and began incentivizing people to buy homes with tax breaks and by letting them borrow against the equity in their current home to buy more homes. (Which helps to explain why one in three homebuyers in Canada is an investor.) Giving tax breaks to homeowners makes a certain amount of sense in some circumstances, but in Canada it has encouraged demand in a market with already way too much of it. Researchers at the University of British Columbia argue that Canada needs to build at least one million non-market homes over the next decade to reduce demand for privately owned housing; Ottawa, moreover, should also probably do away with some of its demand-boosting policies.

What does all this mean for typical Canadians?

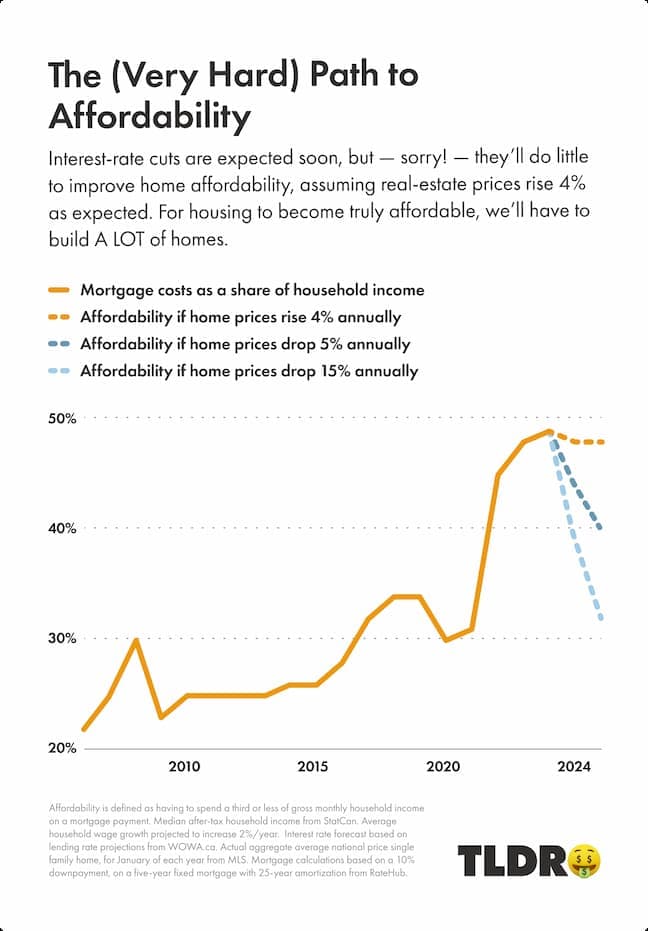

Housing is considered affordable when households have to spend no more than a third of their monthly income on rent or mortgage payments. Well, right now, based on our calculations, the average Canadian couple who owns an average-priced home, which currently costs $776,300, are spending 49% of their monthly income on their mortgage. Lots of people are assuming that that ratio will fall when the Bank of Canada cuts interest rates soonish. But affordability likely won’t improve all that much. (See the chart below.) Any meaningful improvement in affordability would, based on our math, require home prices to drop at least 15% annually over the next couple of years. (That, or wages would need to shoot up wildly, which, we hate to say, seems less possible.) If you agree that the policies outlined above could help drive down prices, housing advocates, like Matthew Desmond, would encourage you to show up to zoning-board meetings to push for change.

One the biggest issues that the housing crisis raises might be about how to build wealth in Canada. For a long time, investing in a home was incredibly lucrative for people who could afford one. But you could argue that real estate really isn’t how Canadians should be trying to grow their wealth. Housing unaffordability has helped keep people poor, and from an investing perspective, if most of your money is tied up in your home, that’s a very concentrated (i.e., risky) investment. And real estate might not even provide you the best returns: the TSX outperformed Canadian real estate over a recent 25-year period. Plus, equities are nice because you don’t have to move out of them to cash out or change your risk profile. Of course, the stock market can occasionally be a dumpster fire too, as 2022 reminded investors. But there’s a difference between a sustained dumpster fire, as with housing, and a cyclical, run-of-the-mill dumpster fire. Many Canadians, it has become clear, would prefer the latter.

Sarah Rieger is a senior news writer for Wealthsimple Media, and co-host of the TLDR podcast. She was previously a reporter at CBC News and editor at HuffPost Canada. You can reach her at srieger@wealthsimple.com.