Money & the World

Why Does Everyone Care About Commodities All of a Sudden?

The first half of 2022 was tough on most markets. But one type of investment has been having a strong run: commodities. Why is that, exactly? Also, what is that? And can someone who’s not ready to store 50,000 pounds of cattle get involved?

Wealthsimple makes powerful financial tools to help you grow and manage your money. Learn more

Unfortunately, most people’s knowledge of the commodities market begins and ends with some vague thoughts about pork bellies, gold, and Eddie Murphy. As obscure as they seem, however, commodities are a vital part of the economy. And early this year, they’ve been a lucrative one.

But who is investing in them? Important follow-up: how does someone invest in them? To answer those questions — and make sure none of us have to store 40,000 gallons of orange juice in the garage — we spoke with Wealthsimple’s Chief Investment Officer, Ben Reeves.

Sign up for our weekly non-boring newsletter about money, markets, and more.

By providing your email, you are consenting to receive communications from Wealthsimple Media Inc. Visit our Privacy Policy for more info, or contact us at privacy@wealthsimple.com or 80 Spadina Ave., Toronto, ON.

What is a commodity anyway?

Commodities are simply raw materials or physical goods used to produce something else — like lumber for your deck, oil for the gas in your car, pigs for bacon, etc. They come in several broad categories: metals (gold, silver); energy (crude oil, natural gas); agriculture (soybeans, lumber); and livestock (cattle, pork bellies). Some commodities even have names that sound like rock bands. (Rough Rice and The Lean Hogs would have killed it at Coachella.)

Have they been around long?

Commodities? We’re pretty sure pigs and cows came a couple of days after Adam and Eve. As for the markets, those started in Chicago in the 1800s. Back then, farmers travelled into the city and made deals to sell their crops before they were harvested. To lock in their eventual payments, they sold forward contracts guaranteeing a particular amount of the commodity for a particular price at some upcoming date.

Recommended for you

The Story of the Stock Market, Told by Five Companies

Money & the World

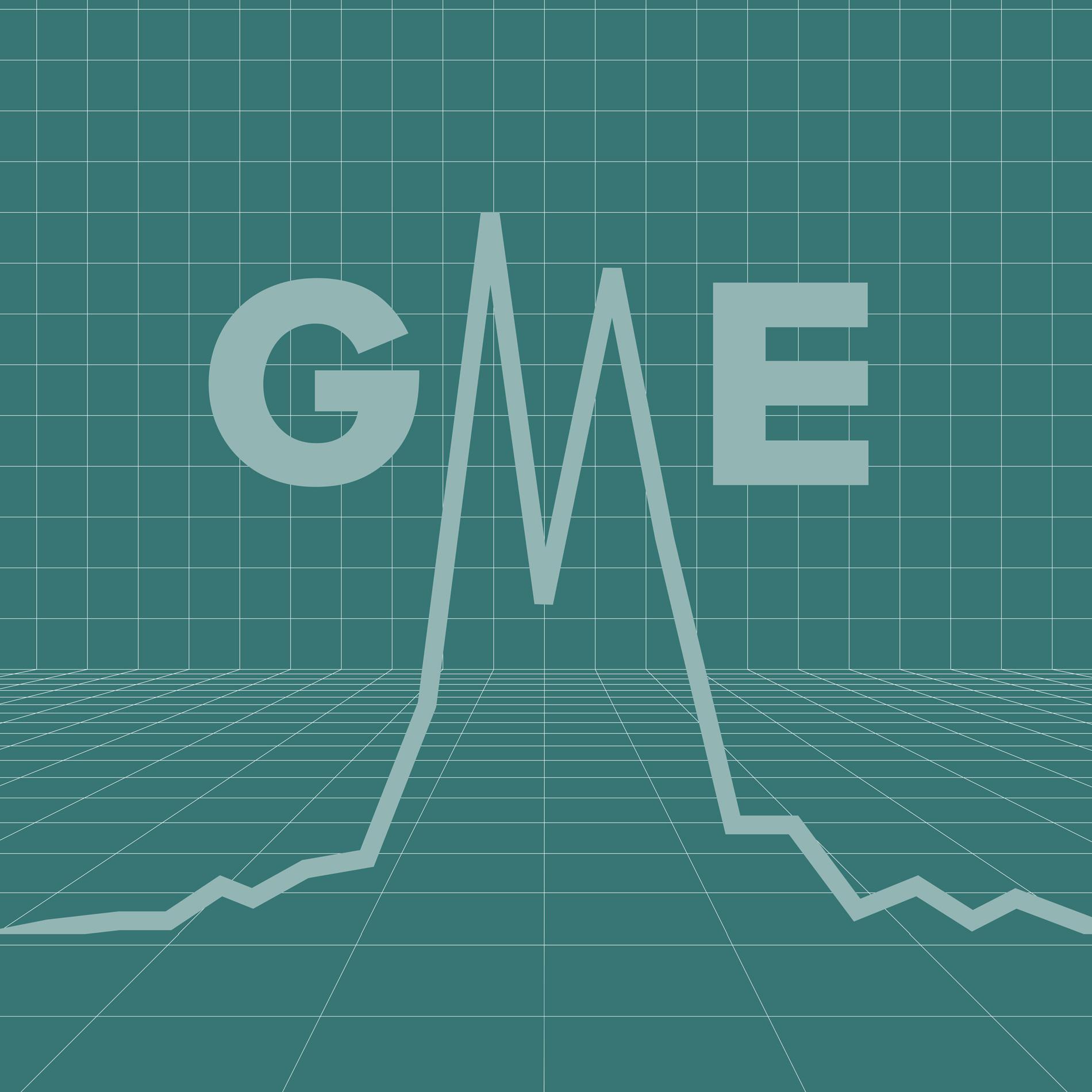

Data: Who Really Traded GME? Why? And What Happened to Them?

Money & the World

The Racial Wealth Gap Is a Problem

Money & the World

Dumb Questions For Smart People: Why Parenting Inequities Make Mothers Leave the Workforce

Money & the World

Eventually, a market developed to replace these one-on-one deals. With it came several advantages: contracts were sold for standardized amounts and with standardized durations. Plus, they were guaranteed by the exchange, so if Wyatt’s House of Wild West Flapjacks defaulted on their agreed-upon 500 hogs, a farmer in Peoria wouldn’t go bankrupt.

The markets also meant other people could get in on the action, buying and selling contracts in the hopes that prices would rise, the same way people currently invest in stocks and bonds. Standardized commodities contracts are called “futures contracts” and apply to everyone, as opposed to those original “forward contracts,” which were only for the private seller and buyer.

Why did commodity prices have such a strong start to the year?

A too-familiar combination of worker shortages, shipping challenges, and pandemic-driven hoarding, plus Putin’s goose-stepping into Ukraine. As the supply of raw material has gone down, prices for them — and for the goods that require them — have soared.

Why do people buy them?

Apart from being fun to talk loudly about in a bar (“You’re in what? Salmon futures?”), commodities tend to move independently of stocks and bonds, so they’re often used to diversify. They can also protect against inflation: when prices go up at the grocery store, commodity prices go up, too.

How does someone invest in commodities?

Markets like the Chicago Mercantile Exchange let you buy futures contracts, which means you agree to buy something for a certain price at a certain time. But if you don’t know what you’re doing, you could end up losing a bunch of money — or having 5,000 pounds of cow dropped off in your garden. The easier way is to buy shares in companies that mine, refine, or farm commodities, or ETFs that track commodity prices.

Can that really happen with the cows?

Yes, but it’s rare. Futures contracts can be physically- or cash-settled. Physical settlement is the one with the livestock truck, but many exchanges won’t allow it without a lot of advance prep and rigamarole. Most people cash-settle: when the contract ends, whoever owes money pays it before bailing from the investment entirely or rolling over into a new one. No manure shovelling required.

Jacqueline Detwiler-George is a former editor at Popular Mechanics and the former host of the Most Useful Podcast Ever. Her work has appeared in New York Magazine, Esquire, and Best American Science and Nature Writing.

The content on this site is produced by Wealthsimple Media Inc. and is for informational purposes only. The content is not intended to be investment advice or any other kind of professional advice. Before taking any action based on this content you should consult a professional. We do not endorse any third parties referenced on this site. When you invest, your money is at risk and it is possible that you may lose some or all of your investment. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Historical returns, hypothetical returns, expected returns and images included in this content are for illustrative purposes only.