Money Diaries

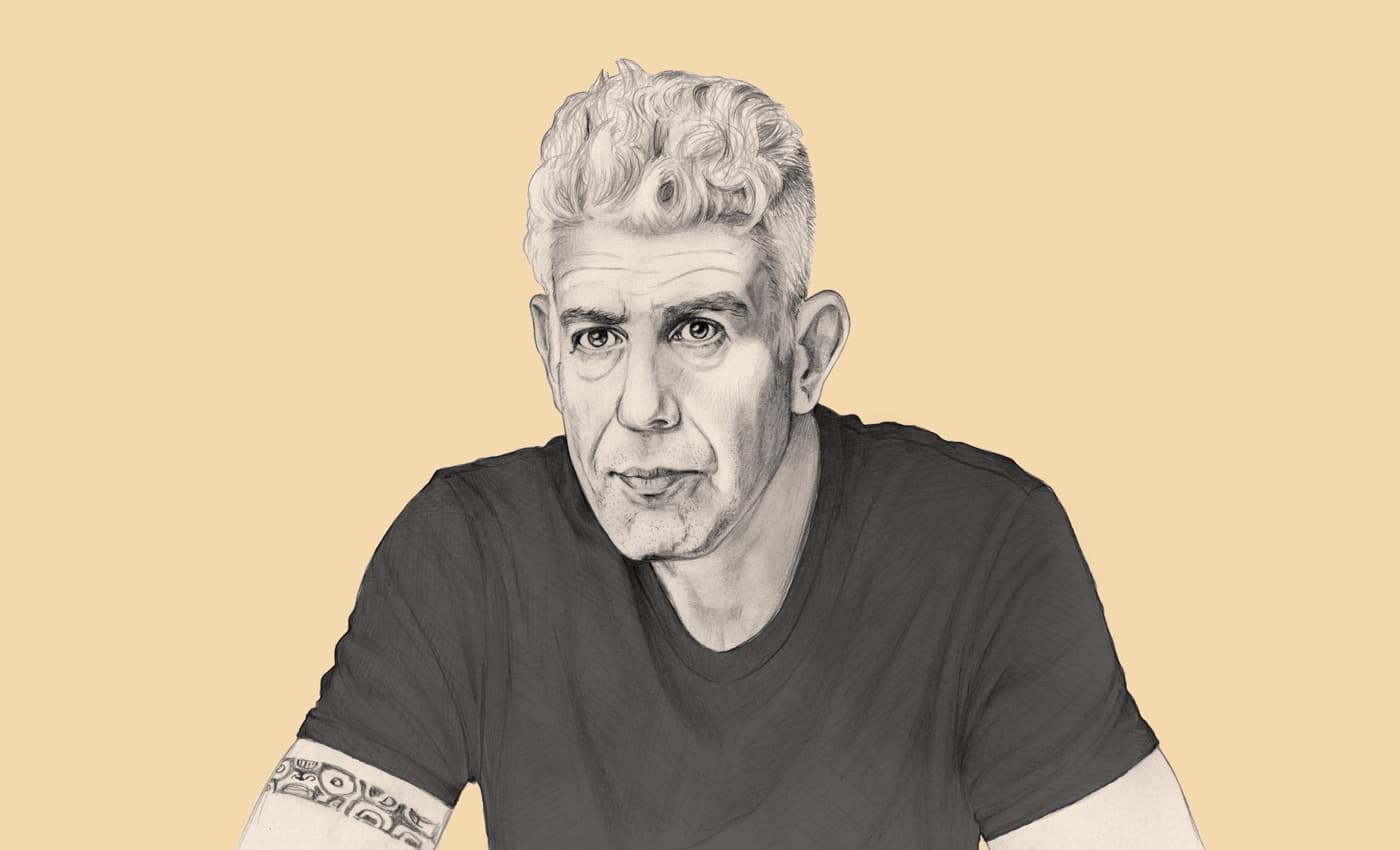

The Financial Coming of Age of the “Can You Hear Me Now” Guy

What happens when you star in an ad campaign for almost ten years that comes to define you? And then get hired by a rival company? Paul Marcarelli explains.

Wealthsimple makes powerful financial tools to help you grow and manage your money. Learn more

Wealthsimple is an investing service that uses technology to put your money to work like the world’s smartest investors. In “Money Diaries,” we feature interesting people telling their financial life stories in their own words.

When I first started making semi-serious money, I never felt like I’d properly earned it. Clearly, I thought, I must have sold out or turned my back on some kind of artistic calling. I had started using my commercial earnings to seed the production of films I’d written, and because of how I felt about my money, the success or failure of those films always came with inordinately high personal stakes. It was as if any kind of approbation for this creative endeavor would absolve me of the sin of financial success.

Growing up, money was just something other people had. My parents were both teachers. When my twin brother and I were born, my mom stayed home for the first few years, so my dad was the only earner. I’m pretty sure he was making in the low teens for a family of five. Then, when I was two, we moved to a small farm, and we supplemented our income with what we could produce from the farm: peaches, tomatoes, chickens, raw milk, Christmas trees, livestock. I got paid for my work on the farm: once a month we’d slaughter chickens, for instance, and I got a quarter for every chicken I plucked.

I spent that money at Roller Haven on Saturday afternoons after a lunch of sautéed chicken livers.

My dad took other jobs too. He spent summers working with a carpenter. He cleaned the local church on Saturdays and my brother and I would go with him and help wax the pews. On Sundays we’d go to church and watch the other kids in their Izod shirts sliding across those same pews, blissfully unaware that one of their peers had buffed them to that perfect shine. I was never ashamed or anything — there was never any shame in working hard for your money.

On the contrary, I somehow got the message that having too much money was something to be ashamed of and that the symbols of that wealth were distasteful.

As a kid, I recall believing that having money somehow indicated you were morally or ethically compromised. There was a beautiful house that was very out of place in my solidly working-class town, this 1930s Tudor that always had super classy Christmas decorations. Every time we passed this house, I would say, “That’s the house where the crook lives.” I have no idea where I’d heard that the owner was a crook. In fact, I’m sure he wasn't. Maybe just a lawyer or a businessman — a concept familiar to me only from TV, boring dudes in gray suits. I somehow learned from my parents that these men were not to be trusted.

Sign up for our weekly non-boring newsletter about money, markets, and more.

By providing your email, you are consenting to receive communications from Wealthsimple Media Inc. Visit our Privacy Policy for more info, or contact us at privacy@wealthsimple.com or 80 Spadina Ave., Toronto, ON.

My parents were always extremely careful with the money they made. I remember during the summers when my Dad was off from teaching, I’d accompany him to the Board of Ed (Education) building once a week to pick up his check. He had been given the option to structure his pay so that he would receive checks every two weeks throughout the summer, rather than getting paid a little more in each check, but only during the school year. He made that choice because one year we ran out of money in July. I internalized the anxiety surrounding this event. And to this day, even though I save and invest wisely and conservatively, I am convinced that any minute I am going to fuck it all up.

Some days there’d be ten checks waiting for me in my mailbox. I made more than $30,000 for one day of work. It was mind-blowing.

That said, I also know that if it did come to that, I would be just fine. I like having nice things and eating good food, and traveling and living in nice places, but if it all went away, I’d be just fine working in a coffee shop, which I did in college; it was by far my favorite job ever.

I received my first serious paycheck as an actor after crashing a commercial audition in the mid-90s. I ended up booking what turned out to be a series of three commercials for Old Navy. I had no idea the job would be as lucrative as it turned out to be. And since I didn’t have an agent yet, the residuals came directly to me at home. Some days there’d be ten checks waiting for me in my mailbox. I made more than $30,000 for one day of work. It was mind-blowing. The first thing I bought was embossed stationery because I’d received a note once from Eric Bogosian on personalized letterhead, and I thought that was pretty much the coolest thing I’d ever seen.

I also took a check to my parents’ financial advisor. A few years earlier, I had opened a brokerage account with her with a single check for $600, instructing her that from that day forward she was to treat each check as if it was the last one I would ever earn. She thought that was adorable and dutifully opened an IRA for me. I’ve been with her ever since. And to this day even though the number of zeroes has increased, we still map out our investment strategy with that same ethos. Finding someone you can trust to exhibit patience and understanding as you learn to manage your money is essential.

For the most part, I’ve been very responsible with my money, but there was one period of time in my mid-twenties during the commercial actors strike when I got into bad credit card debt, and I needed a friend to bail me out. It was a horrible feeling — since then I’ve never bought anything I couldn’t afford to pay for in cash. And I never carry a balance over from one month to the next. But that period of time also taught me a lot. Relying on any one source of income is the easiest way to find yourself trapped or beholden to others. You should always have a side game. I ended up waiting tables a couple nights a week, and then I took a part-time job with a publishing consultant who hired me to coach authors for television and radio interviews. Even though I wasn’t flush, I felt a little bit more secure with money coming in from a few different sources as I paid off my debt.

When the Verizon job came along in 2001, I was basically debt-free, but broke. In fact, I was in charge of buying the turkey that year for a big Thanksgiving potluck with friends. I’d reserved the bird, but I had no idea how I was going to pay for it. Part of my first Verizon check covered the bird. And it was delicious.

Certainly, the Verizon job changed things, butI was always afraid the job was going to go away, so I never felt secure. And since I was working for them pretty much full-time, it also meant that I was back to a single source of income. For something like twelve years, every time they picked up another option year, I would have exactly one day in which I felt OK, then 24 hours later I started obsessing again about whether or not I’d be fired by the time the year was out. In retrospect, I think it was in part the way corporate America benefits from making you feel your role with them is utterly dispensable. How else can they manage to get salaried workers to stay at the office until midnight and be within phone’s reach on weekends and holidays and during funerals and weddings and vacations without any additional compensation!? That shit’s illegal in France! A boss calls you on vacation, you can call the cops.

Recommended for you

How to Quit Your Job and Bike Around the World for $17,000

Money Diaries

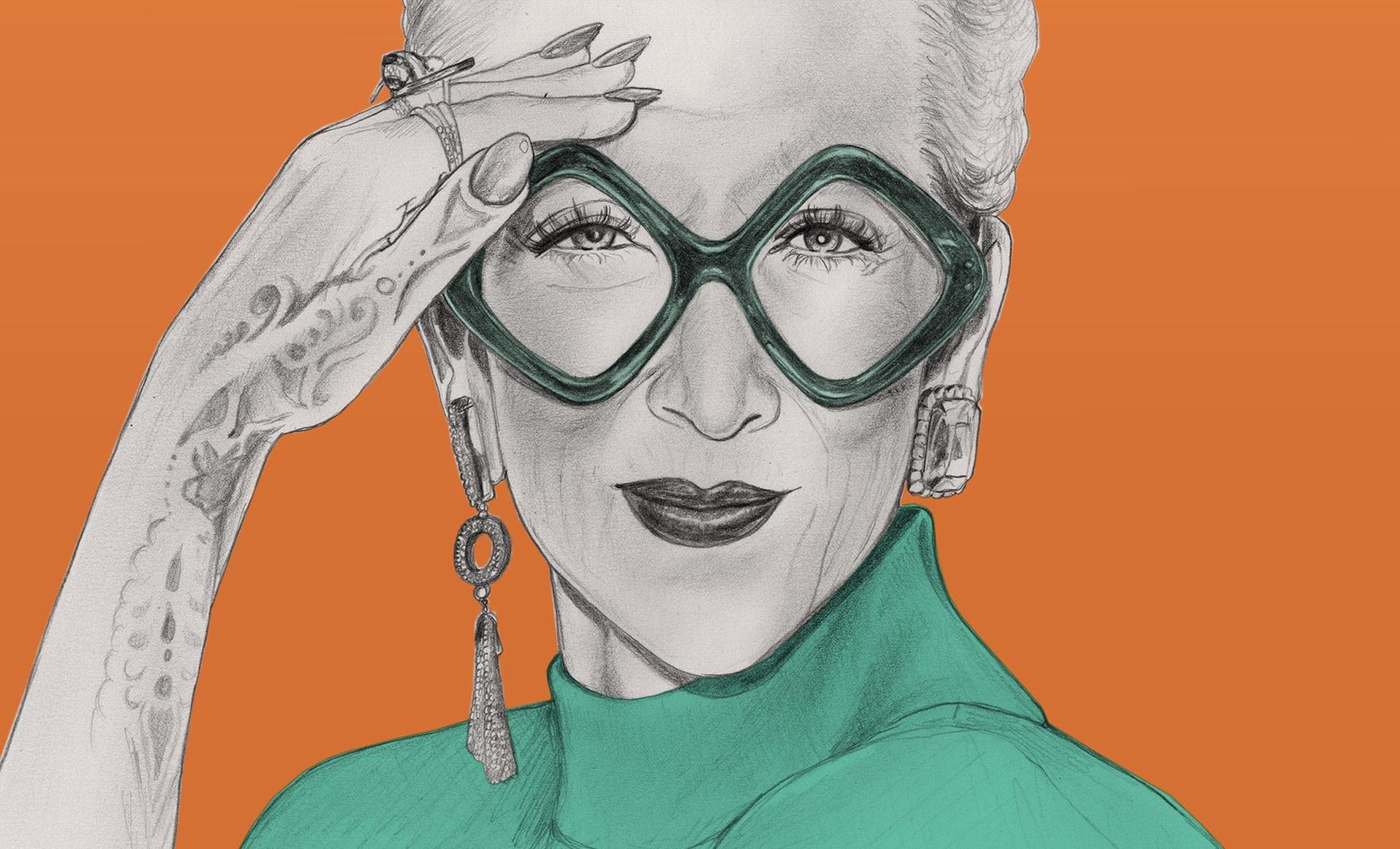

Joel Kim Booster Was in Massive Student Debt Until Two Years Ago

Money Diaries

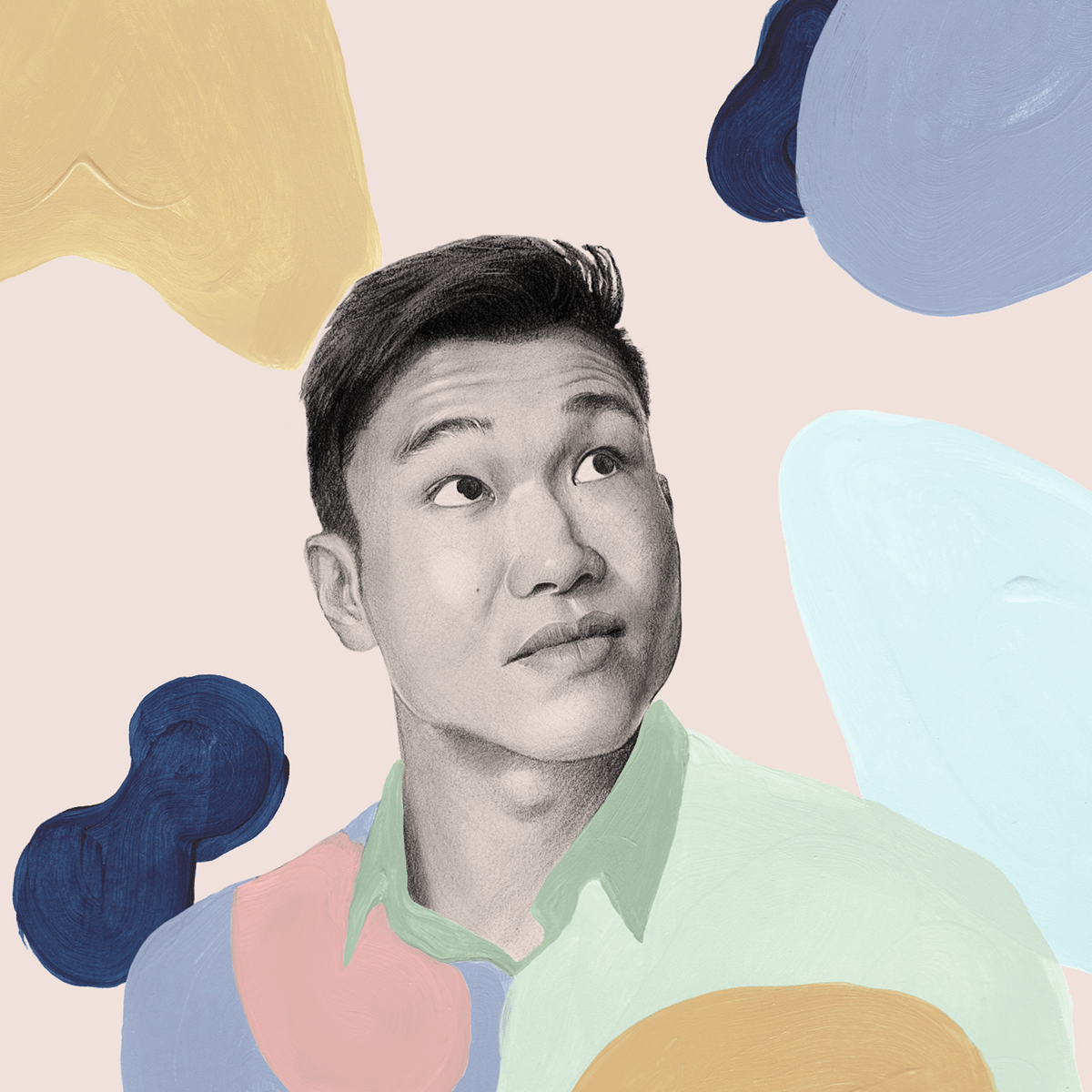

Anthony Bourdain Does Not Want to Owe Anybody Even a Single Dollar

Money Diaries

Natasha Rothwell's Character in “The White Lotus” Finds an Angel Investor. Her Real Life Didn't Quite Work That Way.

Money Diaries

But the other part was all me: that lingering sense that I somehow hadn’t earned this through hard work — like plucking chickens — so I didn’t deserve it. And people seemed to think I’d just accidentally tripped over some leprechaun’s pot of gold. I can’t tell you how many times people said, “Dude, you won the friggin’ lottery!” Even people I worked with would say that, or at least intimate it. And while I acknowledge the luck that is inherent in any good thing that happens to you in your life, I’m also like, “When you win the lottery all you have to do is show up and cash in the damn ticket!”

The work is well-paid, but you may surprised to know that it's actually a lot of work — the kind of thing that requires lots of travel away from friends and family, and I never know where I’m going to be from one week to the next, year after year.

Verizon chose to go in a different direction with its advertising, so my relationship with them ended in 2014. What’s interesting is, looking back on it, it wasn’t until Sprint came along a couple years after the Verizon deal ended that I realized that even I had somehow chalked it up to luck a little bit. But I know that you make a living in this business for twenty years it's no small thing — you're a professional,you're working hard, it's a huge business and you have a big role in it. And because of that, it was a lot easier to ask for what I knew I was worth.

I still take the work itself personally, but when it comes to the compensation, that part’s just business now. It’s not a referendum on my value as a human. Certain things cost what they cost, and I’ve come to learn that objectively assessing your worth is a pretty strong negotiating position.

My sense is that people born rich look at money like hair. It sucks when the stylist cuts it a little too short, but you know it’ll grow back.

Feeling like a grown-up isn't always instinctive, though. I’ve had the same people managing my career and finances since long before I was a big earner, some of whom might still be tempted from time to time to remember me as the kid who couldn’t afford the Thanksgiving turkey. That is not the position from which to begin a negotiation. But that's on me. Part of my job is asserting myself (and trying to be seen) as a grown-up professional, as opposed to a hungry neophyte.

When you aren’t raised with a lot of money, but come into it in adulthood, you have to learn how not to have emotions around it. My sense is that people born rich look at money like hair. It sucks when the stylist cuts it a little too short, but you know it’ll grow back. But if you're born poor and go on to make a lot of money and then lose some of it, it can feel more like losing a limb. A bad financial decision can validate all your fears about money and your ability to manage it. And that morphs into fears about your inability to manage everything else in your life: your relationships, your health, your creative life...

If I had to tell someone what I’ve learned, I would say money fluctuates in value both materially and in what it can do for you throughout your life. But make no mistake; it is a thing, not a construct or metaphor. It is not a symbol of any other thing. It does not represent some other thing. It is the thing itself. It is not a lover or a friend or a family member or even a wonderful pet. Likewise, it is not an enemy, an adversary, or an ex. And so you should not engage in an emotional relationship with it.

Hands down the best investment I ever made was my apartment in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, which I sold last May. It was an emerging neighborhood that I didn’t mind living in for a while as I waited to see what the area would become. Turns out, I didn’t much care for what it became, but a lot of other people did. When we were ready to sell, that helped. I've actually invested in several homes over the years. Each time, I knew I would enjoy living in them as I fixed them up. But I always do my research to make sure I’m buying something that is undervalued, so in case the worst should come to pass, the place would sell relatively quickly and hopefully at a profit. I look for properties that are eccentric in some way, places that aren’t for everybody. I always feel I’ll have better luck finding a buyer if the field of buyers is narrower. That seems counterintuitive, I know, but it works for me.

The worst investment was also kind of great: Making films. Although I’ve not made any serious money producing films, there is a very enriching feeling you get when seeing an idea you had all the way through.

And it actually helps counterbalance financial fears, which is kind of interesting. I remember I was shooting a commercial in Toronto when the stock market crashed in ’08 or ’09. I had the day off, and I was working on a rewrite of a film I’d written that I planned to produce. My dad called because my mom was very concerned that I might have lost all my money. The conversation went something like this:

Dad: “Did you lose a lot of money today?”

Me: “Maybe. I haven’t looked. I kinda feel like if the whole thing collapses I'll still have the ability to make things. I’ve been writing like crazy all day. It’s kind of reassuring.”

Dad: “Funny. I feel like I’ve been preparing for this my whole life. I just went out and tilled a new field for spring just in case we need to produce more food. It's good — you are definitely a farm kid.”

As told to Jane Larkworthy exclusively for Wealthsimple; transcript edited and condensed for clarity. Illustration by Jenny Mörtsell.

Wealthsimple's education team is made up of writers and financial experts dedicated to making the world of finance easy to understand and not-at-all boring to read.