Money Diaries

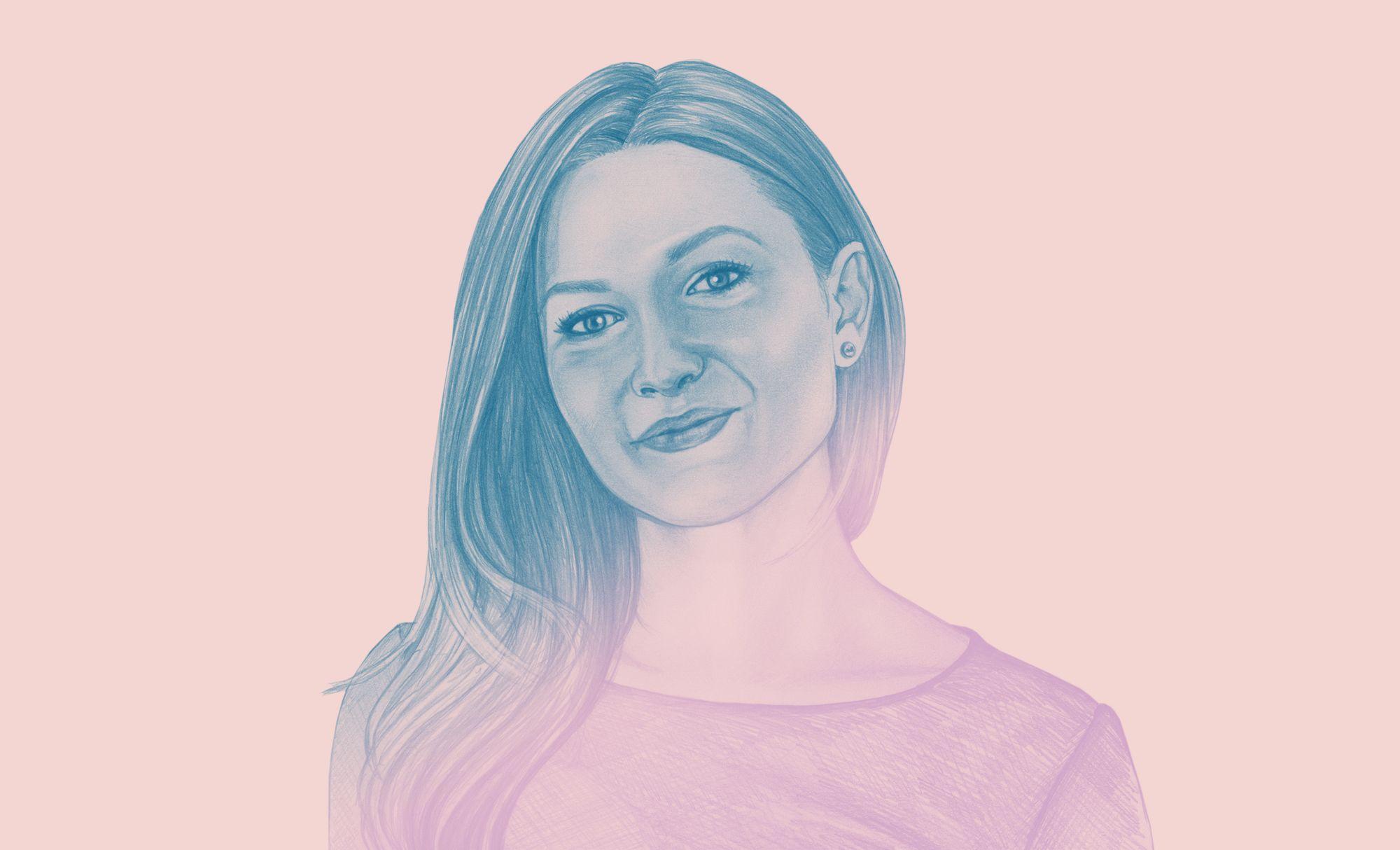

“Why Wouldn't a Woman Want to Win?”

Jen Agg may be one of the most successful bar and restaurant owners in Toronto. But it doesn't make her less restless.

Wealthsimple makes powerful financial tools to help you grow and manage your money. Learn more

Wealthsimple is a whole new kind of investing service. This is the latest installment of our recurring series “Money Diaries” where we ask interesting people to open up about the role money has played in their lives.

When I was a kid of 9 or 10 my dad wanted me to clean up all the pine needles that had fallen into the cracks on the balcony at our cottage. And he said, “I’ll give you a penny for each needle.” So I cleaned the whole deck. I spent the whole day bundling all the needles, and I had them all organized. He owed me something like $90. To this day, that’s how I approach most things. I’m very determined. I do things thoroughly and I like to win. I haven’t changed much, I’m just a little better. Winning is not something a lot of women talk about or are made to feel good about. But why wouldn’t a woman want to win?

My parents would always pay me for doing chores. It wasn’t usually $90, but it was always exciting to me. Money was never just handed to you, which motivated me even though I was only spending my money on Oreos. Sometimes I’d eat an entire sleeve of Oreos and feel so bad but so good afterwards. That’s where the petty cash went. Then I got my first bartending job at Toby’s, a downtown pub, when I was a teenager. I did lunch, and I’d make like $120. Which felt like winning the fucking lottery. I couldn’t believe that I could get these chunks of cash and walk out with it, go a few blocks over to the Dance Cave and spend it in one night. At that point, I was good at making money, but not good at holding onto it.

Sign up for our weekly non-boring newsletter about money, markets, and more.

By providing your email, you are consenting to receive communications from Wealthsimple Media Inc. Visit our Privacy Policy for more info, or contact us at privacy@wealthsimple.com or 80 Spadina Ave., Toronto, ON.

I didn’t know then that I would open a restaurant. I wasn’t thinking entrepreneurially. When I was older, I ended up at Souz Dal, a cool cocktail bar in Toronto. I felt I belonged there at first. But after a year or so, I decided I could do it better. My boss there took too large a cut of his workers’ tips, more than was fair. That really stuck with me. Now that I’m a restaurant owner, I only take a cut of the tips if I’m working a full floor shift. And when working full services, my goal is always to work harder than anyone else on the floor, as both a point of pride and as a gesture of respect. No job is too menial, no sink too puke-y for me. If you want people to work hard for you, you have to demonstrate a willingness to do the same.

When I was 21, my parents very generously made me an offer. They would either help me with a down payment on a house, or give me a business loan. I took the latter, and opened my first bar, Cobalt, with my first husband. Being in charge was amazing. I took to it like a fish to boozy water, even though managing a bunch of kids my age wasn’t always the best situation.

I still remember which stupid printed t-shirt I was wearing when a bank teller told me that my account was frozen.

Cobalt was an eight-year bar. That’s real longevity, by bar standards. But I had no idea, for the last half of its life, that the business was going downhill. My husband was managing the books, and he just wasn't paying taxes for the last few years. Being a novice owner, I hadn’t incorporated, so it was all in my name. I still remember which stupid printed t-shirt I was wearing when a bank teller told me that my account was frozen. That was another good lesson. You need to be perceptive and in control. Even though I have an incredibly good bookkeeper, I look at my accounts every single day. I look at the money coming in, and scrutinize unusual expenditures. It’s a little bit crazy.

As Cobalt was floundering, and my first marriage was ending, I met my now-husband, Roland. And for two years after Cobalt closed, I was basically a housewife. It was a really happy life — we were really in love and I thought I could enjoy a peaceful existence. But I was still ambitious. And when a bar near us went out of business, Roland and I rented their space and built my first restaurant. Starting with a place that already has bathrooms and a bar is something I’d recommend to any young mind wanting to get a start in this industry. Because of what was already there, we opened The Black Hoof for $70,000, which is pretty unusual. You don’t get to open restaurants that cheaply.

I try to be ahead of the curve, but not so ahead of the curve that nobody knows what the fuck I’m doing.

Recommended for you

Anthony Bourdain Does Not Want to Owe Anybody Even a Single Dollar

Money Diaries

How I was Conned by the “Fake German Heiress”

Money Diaries

Pandemic Money Diaries — Panic at Trader Joe’s Edition

Money Diaries

She Was Living in a Shelter Six Years Ago. Now She’s the CEO of Her Own Beauty Company

Money Diaries

For the first couple of weeks, the Hoof was empty, and I was just watching my money fly away. It took a long six weeks for the first rave review to come in. But then it hit. At that point, it wasn’t similar to anything else out there. Nobody had combined loud music, unusual food, chill vibes, and careful service in the same way. If anything, this is what’s made me successful. I try to be ahead of the curve, but not so ahead of the curve that nobody knows what the fuck I’m doing.

So I had gone from bankrupt at 29 to owner-operator of the city’s most hyped restaurant at 32. But that wasn’t the end of this weird vortex of success and failure. The first really bad thing that happened was that my partnership with the Hoof’s first chef, Grant van Gameren, turned out to be really awful. To his credit, he’s a very talented cook, and he brought a lot of creativity to the food. Even in New York people were not cooking like he was, with the really odd bits — with like, brains and sweetbreads and hearts, and these things we were working with. But he instilled a really macho chef bro culture in the restaurant. I rail against this for obvious reasons. You’ve got to treat people professionally. When somebody’s washing dishes hard for you, you don’t humiliate them, or make them the butt of a joke, then call it fucking camaraderie. Our partnership didn’t last long.

It’s been and up and down thing since Hoof opened. There were some unambiguous successes. Like, I opened a very profitable cocktail bar across the street from the Hoof, because I wanted somewhere for customers to drink when the restaurant was full and they wanted to wait for a table. I got tired of sending people three blocks away to somebody else’s bar in shitty Canadian weather. But my next restaurant, Raw Bar, got closed by one awful review. And a brunch concept I tried, the Hoof Cafe, was delicious, but a financial nightmare. I just held on. Every failure made me work harder. Now I have four successful businesses of my own in Toronto. And none of them have any backers or investors. Every dime is mine. And I got to partner with The Arcade Fire, one of my favourite bands, to open Agrikol in Montreal.

I could’ve taken an easier route to success. Undeniably. The simplest way to make money in this business is fancy burgers or pizza. I could be making $10,000 more a month, personally, if I was taking that route. But that’s not what I want. I make financial sacrifices to open the kind of restaurants I do, that serve the kind of food I love. At my latest restaurant, Grey Gardens, I get to work with Mitch Bates, the best cook I’ve ever seen.His dishes are so fascinating. He’s a real intellectual. The plates themselves seem simple — maybe it’s a corn ravioli with chorizo and tomatoes — but there is so much technique in every step, and each flavour builds on each other perfectly.

My brain feels like it's always going too fast and I need to be mentally occupied constantly, and that’s what restaurants are about for me.

We don’t even make money on everything we sell. Recently, we sold caviar at Grey Gardens for almost no profit. Our cost for a small tin was $70 — we served it with a piece of fried fish with honey-dill sauce and had it on the menu for $100, which is not even close to a proper restaurant mark up. Once labour and other expenses are factored in, there’s no money left over. In fact, we probably lost money on it. But we did it because we wanted to offer people the chance to eat something exquisite (and normally out of reach), and do it relatively affordably. Sometimes you take the hit.

It’s all worth it because for me, making your diners feel good is just so endlessly satisfying. My brain feels like it's always going too fast and I need to be mentally occupied constantly, and that’s what restaurants are about for me. It's like crack, this shit, it's just so addictive. And for the moment, now that the money is coming in, I’m relatively chill — collecting $200 every time I pass Go, and gathering my thoughts. But it won’t last long. I’ve promised my amazing partners — the bartender David Greig and the sommelier Jake Skakun — that I’ll help them expand, and create their own institutions within my own. I’m looking forward to that. It’s kind of wonderful to take your castle from one turret to three turrets. Letting your partners flourish is the most important thing I’ve learned about being a boss. You have to understand that people are better than you at certain things. Which is hard for a control freak like me. But David’s cocktails are annoyingly great, and Jake’s wine knowledge is amazingly comprehensive.

I have some money now. Roland and I don’t live a totally gaudy lifestyle, though. The best thing about having money is that we can help out our family. It’s just not something we have to stress about anymore. I’m not saying we don’t enjoy nice things, also. I feel like my body was really made to wear Rag and Bone. But donating to the ACLU and Haitian charities feels good, too.

As told to Sasha Chapin exclusively for Wealthsimple. Illustration by Jenny Mörtsell. We make smart investing simple and affordable.

Wealthsimple's education team is made up of writers and financial experts dedicated to making the world of finance easy to understand and not-at-all boring to read.