Money Diaries

The Author of "Power of Habit" On Not Being Intimidated By Money

To Charles Duhigg—author of "The Power of Habit" and the forthcoming "Smarter Faster Better"—financial power comes from understanding what money really is.

Wealthsimple makes powerful financial tools to help you grow and manage your money. Learn more

Wealthsimple is a whole new kind of investing service. This is the latest installment of our recurring series “Money Diaries,” where we ask interesting people to open up about the role money has played in their lives.

I have always enjoyed thinking about money. Even as a kid.

Sign up for our weekly non-boring newsletter about money, markets, and more.

By providing your email, you are consenting to receive communications from Wealthsimple Media Inc. Visit our Privacy Policy for more info, or contact us at privacy@wealthsimple.com or 80 Spadina Ave., Toronto, ON.

I grew up in Albuquerque. My dad was a trial lawyer, and I remember a lot of conversations around the dinner table being about questions of how you compensate certain types of injuries in the damage phase of a trial. He was trying out stuff from his cases on us, like whether he should ask a jury for half a million dollars or a million. For instance, if someone loses a limb in an accident, is a leg worth more than an arm? And even that has its component questions: For a professional soccer player, losing a leg would probably be worth more than losing an arm. And how do you go about figuring out how many dollars an arm or a leg is worth? Or the discussion would be: Which is worth more, a mother or a father killed in a workplace accident? If the mother has a five-year-old child when she dies in the accident, she’s theoretically worth more in dollar terms than if her daughter were 35. I think taking something that seems unquantifiable and finding real and practical ways of quantifying it was interesting to me early.

Money is a language the same way that Spanish is a language.

On top of that, I’ve always sold stuff. In second grade, I would buy stickers at this place called Pennysmiths. I would take the stickers home, put them in a photo album, and then sell them at school at a fairly significant markup. Then the school told me I had to stop selling stickers. So I started selling candy. Then they told me I had to stop selling candy, too. But it was a real discovery that if you took something that anyone could buy themselves and brought it to them, suddenly they’d be willing to pay a different price for it. And even way back then, profit itself was never the attractive part to me.It was the arbitrage that was interesting. It was learning to speak the language of money: what has a value, and where do we come up with that value.

We're constantly trying to arbitrage to maximize what is meaningful and minimize those things that aren't.

Recommended for you

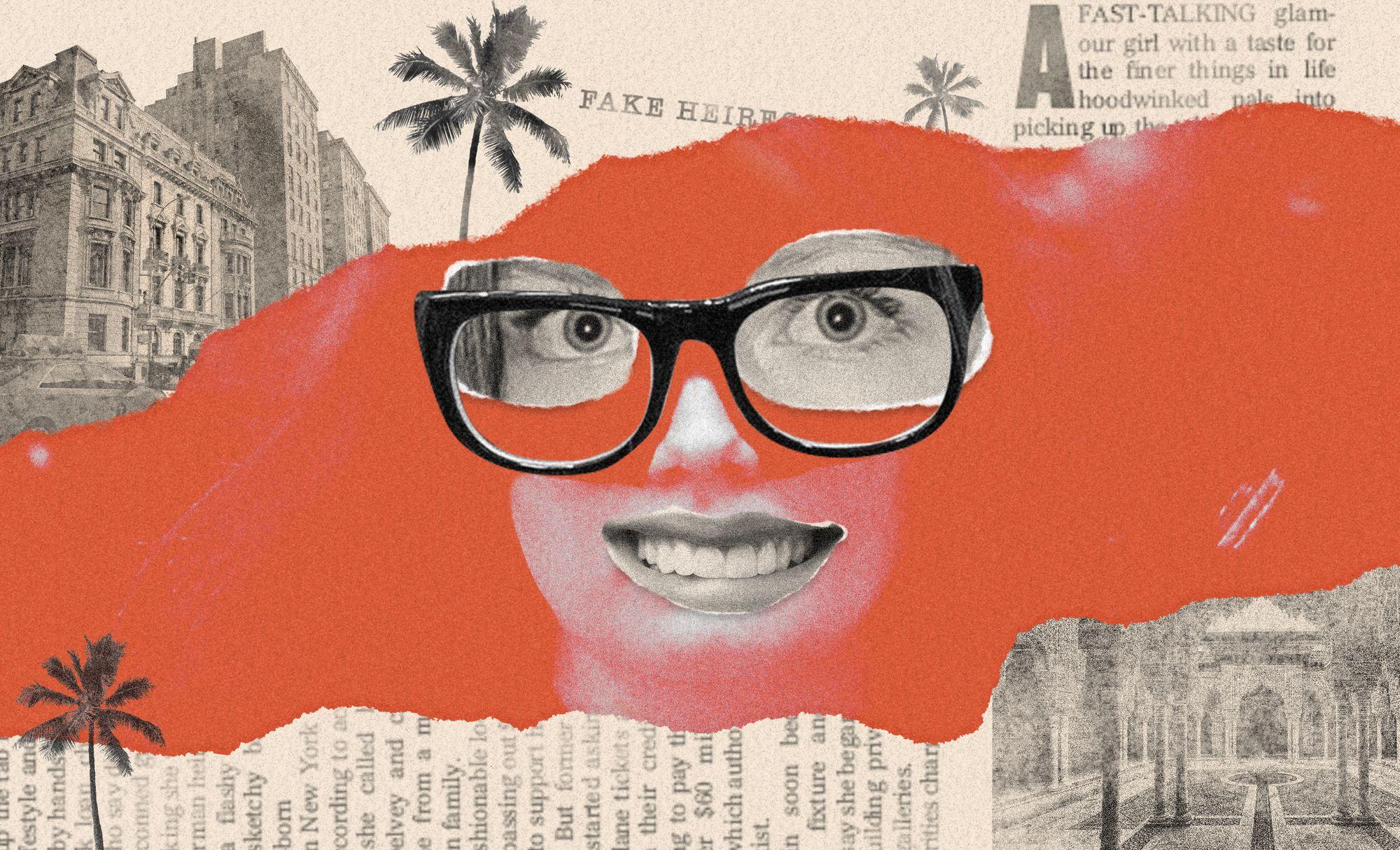

How I was Conned by the “Fake German Heiress”

Money Diaries

To Win Four Oscars, Sean Baker Had to Go Broke Again and Again

Money Diaries

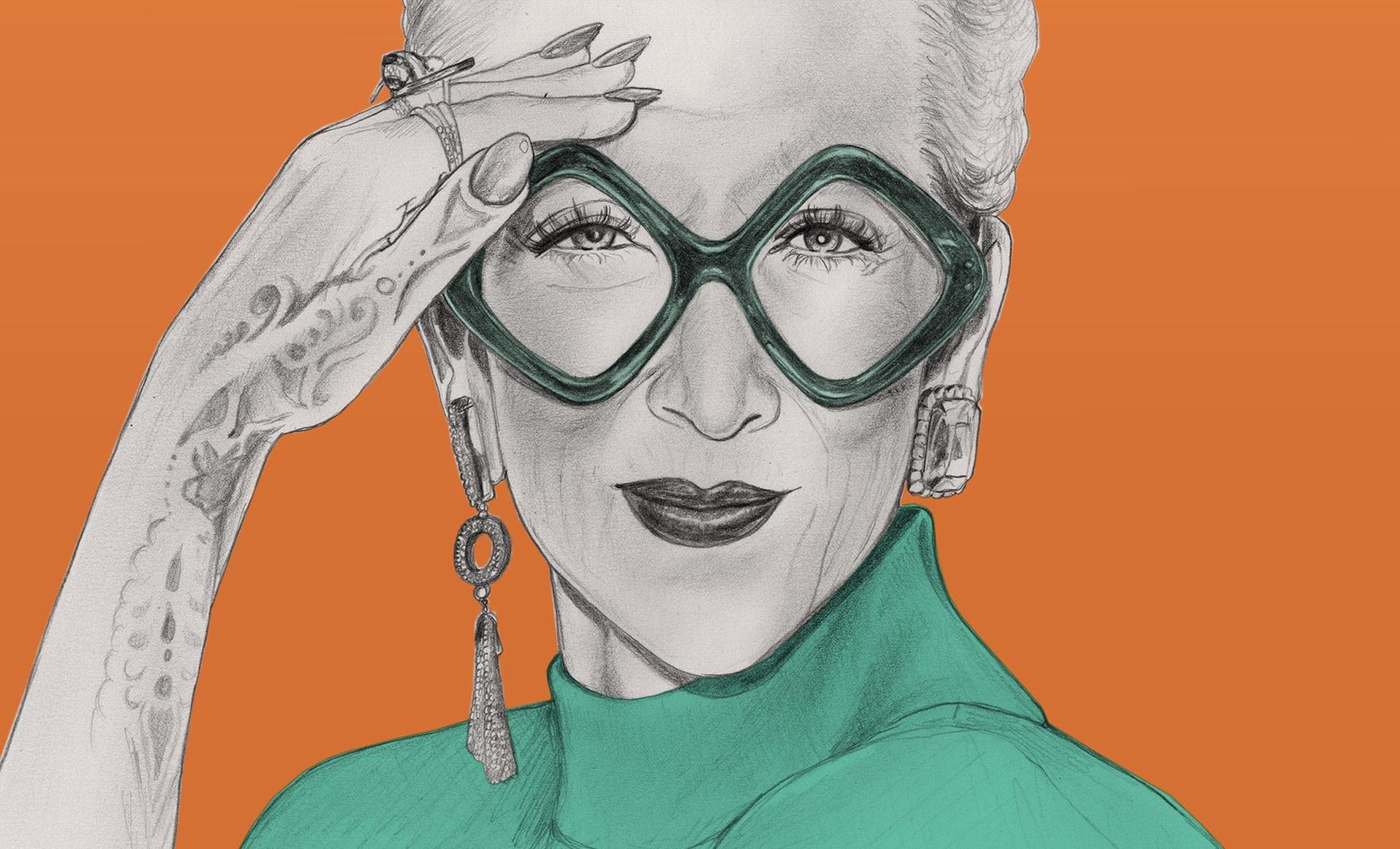

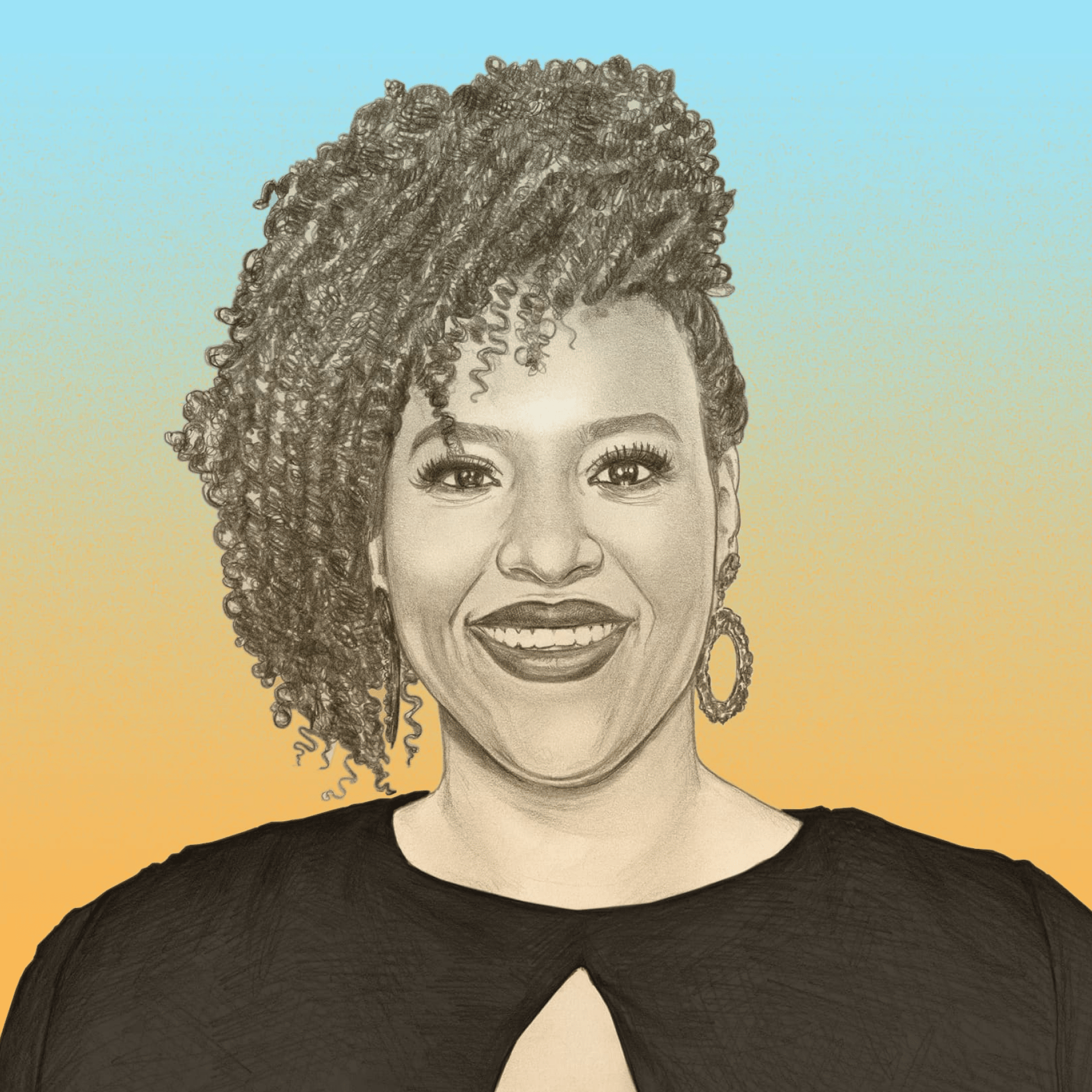

Natasha Rothwell's Character in “The White Lotus” Finds an Angel Investor. Her Real Life Didn't Quite Work That Way.

Money Diaries

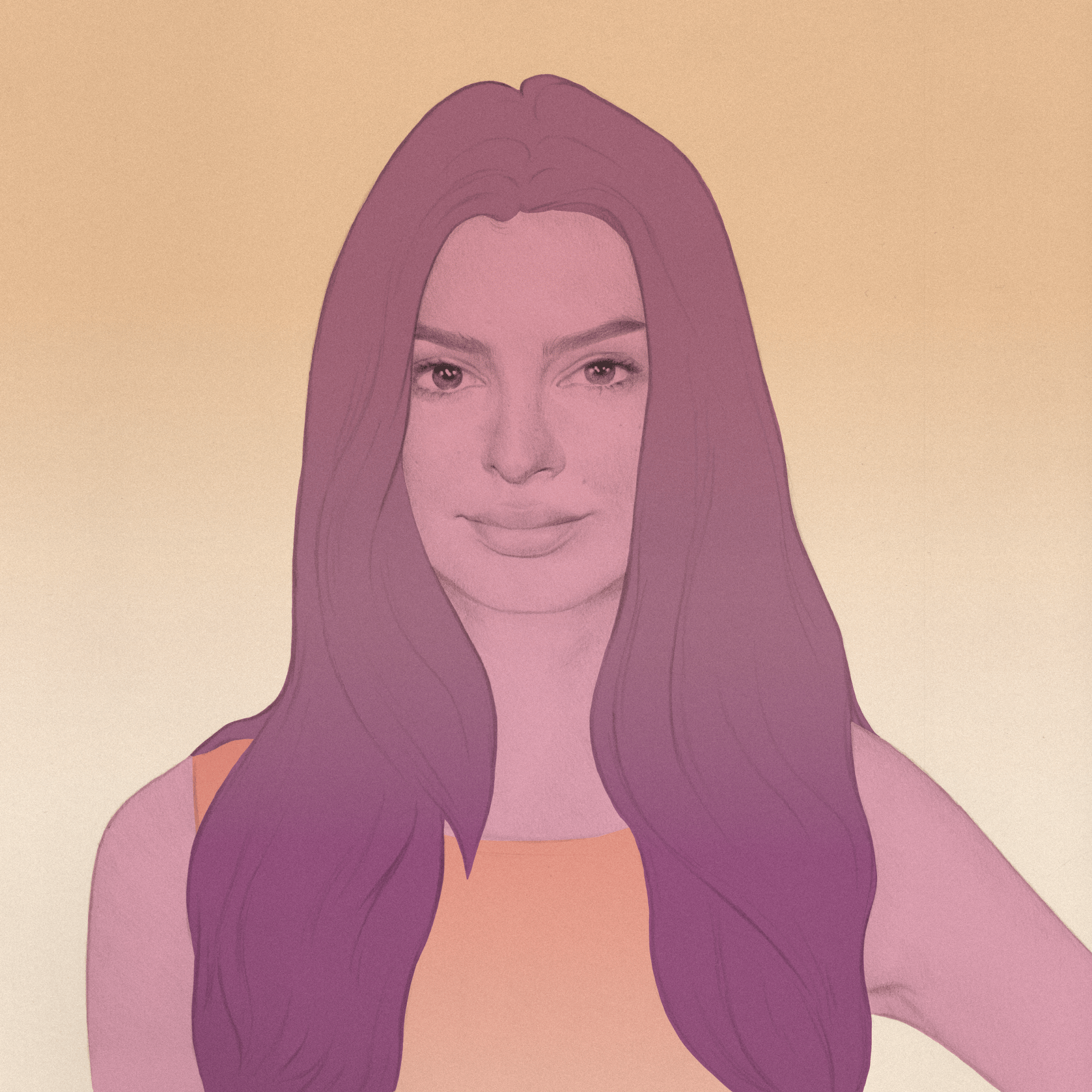

Emily Ratajkowski Is Not a Commodity

Money Diaries

As I got older, I began to understand that money really is a language the same way that Spanish is a language. And people who learn how to be fluent in money have an advantage. A lot of people don’t think of money in those terms. They think of it as a thing in and of itself, that money is this tangible thing called dollars, but that's not right.A dollar is essentially a fungible stand-in for some other type of resource. Time is a resource. Energy is resource. A pension is a resource. Once you understand that a dollar is just stand-in for some other type of resource because we're trying to find some easy way to exchange one resource for another, then you begin to understand how money works. Again, it’s arbitrage. If you think about it, many of the questions we spend the most time thinking about are arbitrage questions: Does it make more sense for you to go to work and hire a nanny or to stay home with your kids? Should you catch up on your emails or spend half an hour talking to your wife? What has more value to you? At the root of that is actually one of the most important questions about what it means to be human—we're constantly trying to arbitrage to maximize those things that are meaningful and minimize those things that aren't. That’s at the root of all economic activity.

I had a different kind of path to becoming what I am today—a journalist and author. I went to Yale, and then I came back to New Mexico, and I started a company with my father in New Mexico that built medical-education campuses. That was a project, and once it was up and running and a little bit stabilized, I went to business school. We sold the company at the end of my first year of business school. Then, between my first and second years, I worked for a private equity group that specialized in real estate, mostly hotel and golf course deals. But I felt that job was less interesting to me than something else I had interest in: being a journalist. In private equity, every deal is unique and has its own problems, of course. But a big part of becoming more successful is learning to deal with the same problems faster and faster. To essentially make your work less interesting. In journalism, it's the opposite. You're basically encountering a different problem every single time. So I opted for the different problem every time choice. It was an arbitrage question. I was aware that people would say you couldn’t make a living at it.But there are people who say there's no money in all types of things. And it was interesting work. I will say, though, for a long time I took a financial hit by becoming a journalist. But since I have always been able to speak money, as a result, I felt that I would be able to make it sustainable for me.

I don’t experience a lot of anxiety about money. When people feel anxiety, it's usually about the unknown, because they're worried that they don't have enough for what's going to come next week or next month. Once a week, I update a spreadsheet that contains all of my financial information so I know down to the last dollar how much money I have in my accounts and how much I have in my investments and how much I have on my credit cards. Most people shy away from knowing that. People get scared about money. I don’t. My habits provide that reward. It makes me feel responsible to know where I am financially.

As told to Andrew Goldman exclusively for Wealthsimple. We make smart investing simple and affordable.

Wealthsimple's education team is made up of writers and financial experts dedicated to making the world of finance easy to understand and not-at-all boring to read.