Finance for Humans

Bond Yields Are Super Low. Some Investors Are Freaked. An Explainer

Falling bond yields usually signal Big Time Economic Trouble. And, at the moment, yields have almost never been lower. Is the economy about to implode or is something else going on?

Wealthsimple makes powerful financial tools to help you grow and manage your money. Learn more

People love talking about the stock market. Bring up bonds, however, and conversations tend to die. Dive into the weird dynamics of what’s going on with the yields of U.S. government bonds and, umm… hello? Where did everyone go? And yet here we are, about to have that exact conversation.

Because, even though bond yields, in particular, might seem mega dull, they’re an important, closely watched economic barometer that tells us how investors think the stock market is going to perform. And right now yields are telling us something confusing, and have some investors and economists stressing about a possible bubble in stocks, but also maybe in bonds, but also maybe in both — any of which would be bad for you and me and virtually every other investor.

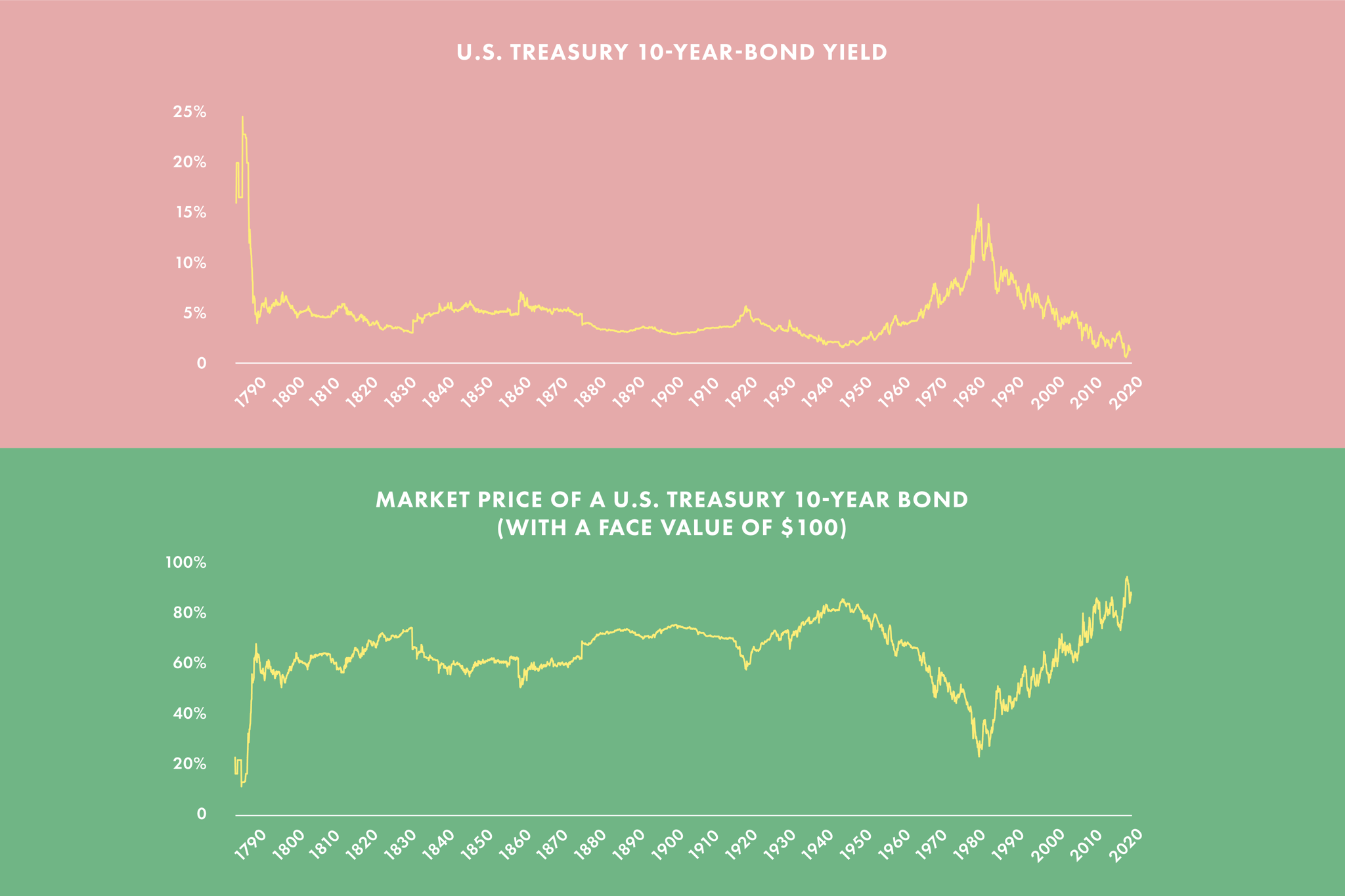

The fretting mostly owes to the fact that low yields typically signal that the stock market, and economy in general, is in trouble. And yields are currently about as low as we’ve seen in modern history outside a major crisis. Yet stocks keep rising and rising. So what’s going on? Are stocks headed toward disaster? And should we all be stressing out, too?

First, remind me what bond yields are, exactly.

Bonds come in many flavours: corporate, municipal, foreign. But, no matter the type, a bond is basically a fancy name for an IOU, or a claim on money owed. (Wealthsimple has an entire bond explainer if you’re dying to know more.) Investors tend to treat bonds as the ugly step-children of their more attractive stock-market siblings. And it’s no mystery why: over the past 100 years, bonds have earned roughly half as much as stocks. And, as of today, if you were to invest in so-called “benchmark” 10-year U.S. Treasuries, you’re signing up to earn a whopping 1.299% (or thereabouts) per year for a decade. Canadian bonds offer similarly ho-hum returns.

Sign up for our weekly non-boring newsletter about money, markets, and more.

By providing your email, you are consenting to receive communications from Wealthsimple Media Inc. Visit our Privacy Policy for more info, or contact us at privacy@wealthsimple.com or 80 Spadina Ave., Toronto, ON.

A bond yield is the fixed amount, expressed as a percentage, that you can expect to earn from a bond over a given chunk of time. I lend you $100. You agree to pay me $1 a year over 10 years for letting you borrow the money, before paying me back my full $100 at the end of the decade. The yield is 1%, or $1 annually. That’s pretty easy, right?

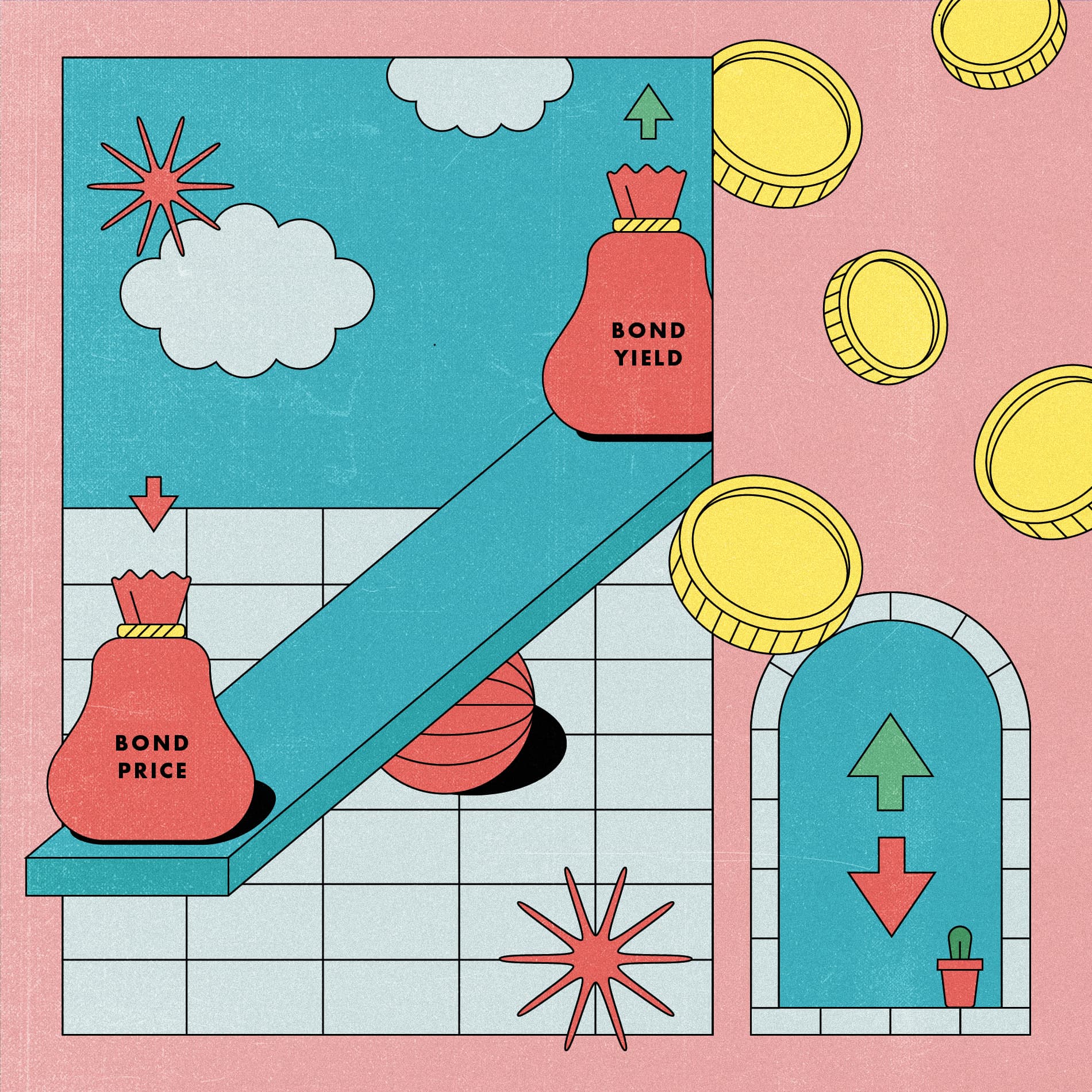

Where bonds get tricky — hang with us — is that the yield tells you nothing about how much you stand to make if you sell a bond. In our above example, let’s say you decide to sell your $100 bond after five years, instead of keeping it the full 10. Well, if the going rate for bonds has dropped from $100 to $80, because of low demand or whatnot, your bond will continue to pay its new owner the same $1 a year, but the yield will change to about 5%, based simply on the math of the deal. The new owner enjoys a higher yield than you because she put up $80 to get $100 back in five years, whereas you paid $100 — plus she still pockets the same $1 fixed yearly payout (sometimes called a coupon payment) that you did. Bond-yield calculations get way more complicated than that, but that’s the gist.

OK, I understand what a bond yield is, sort of. Why should I care?

Treasury bonds, whether U.S. or Canadian, are typically the most boring of all bonds, given their unremarkable-at-best yields. But, since these bonds are fully backed by their respective governments, they’re considered some of the world’s most bomb-proof investments. And because Treasury bonds are so safe and have guaranteed yields, many investors flee — and flee desperately — to them whenever stocks nose-dive. It’s better to get a meh 1.3% yield on Treasury bonds, say, than to lose tons of money if your stocks lose value or to earn virtually nothing by holding cash in a bank. Boring Treasury bonds, in other words, look way more attractive when all the alternatives are terrible.

Here’s where bond yields come into play: when yields fall, it usually means that investors are getting into the bond market and out of the stock market — because the economy is in trouble. And when demand for and the price of bonds rise, bond yields drop. The reason for price and yield’s seesaw, one-up-one-down relationship is complicated to explain and not worth getting into. The important thing to remember is that often, when stocks are in the toilet, a bunch of people will suddenly want to buy Treasury bonds, driving down yields. But nervous investors will buy these low-yield bonds anyway, because they have few other ways to make any money.

The interesting thing happening right now is that stocks are not in toilet territory. Quite the opposite: the major indices have all hit record highs in recent days, unemployment is trending down, and many major North American companies have posted record profits. And yet yields remain low. Yields were lower during the March 2020 COVID crash — but not even a full 1% lower. Most of the time, these rock-bottom yields would trigger serious alarm bells for many Wall Street investors that the economy and the stock market are in hot water, or headed that way posthaste. But that’s not happening in any huge way, because, by nearly every measure, the economy is solid.

So why are yields low if the economy looks strong?

There’s not one neat-and-tidy answer to this question, but a handful of probable ones, since a lot of factors are at work. Bond yields, for one, have generally trended downward over the past 40 years, as major countries have learned how to effectively control inflation. So that’s happening on one level.

Beyond that, perhaps the most obvious explanation for the Quasi-Curious Case of Low Bond Yields is that, to keep the COVID recovery going and to boost employment, all the major central banks really, really want people to spend, lend, and invest in stocks — instead of saving and buying bonds, which slow down the economy. The U.S. Federal Reserve, for one, wants people to invest in stocks so badly that it’s buying $120 billion (!) in government-backed bonds a month — driving up bond prices and artificially forcing down yields. This whole situation makes buying bonds a lousy deal for the rest of us, which is the entire goal. By keeping bank interest rates at basically zero, central banks are also making it a lousy deal to save, since money stashed in banks will earn you next to nothing. The result is that investors have few decent places to put their money except — where else? — in stocks.

The major central banks won’t keep buying bonds and propping up stocks forever (Canada’s central bank dialed back its bond-buying program this summer). But central banks, especially the Fed, have made it clear that they intend to cut back slowly.

OK, my eyes are starting to glaze over. What’s the upshot?

The long and the short of all this is that the economy (probably) isn’t going to implode, and that there’s (probably) not a bubble in bonds, or stocks for that matter. Nothing is for sure — we’re talking about the macroeconomic trends here — but bond yields have remained low, and could stay that way for a while, for completely logical, non-scary reasons that don’t all point to an impending economic apocalypse.

So where does that leave us? Yields are low and bonds are expensive, yes. But it’s still as smart as ever to hold or buy bonds. Since government bonds have guaranteed yields, bonds will help mitigate a surprise market downturn in stocks — never mind that such a downturn looks unlikely right now — and help you earn higher, more consistent returns over time. And, though bonds aren’t cheap, they could certainly get a lot pricier if another downturn rocks the stock market, which would be a less-than-ideal time to shop for them. Canada and U.S. Treasury yields could theoretically fall low enough where it stops making sense to buy bonds. (Japan’s bond yield is basically zero.) But we’re not there yet. And, at any rate, that’s another conversation-killing topic for a different day.

Larry Kanter is a writer based in New York.