Money Diaries

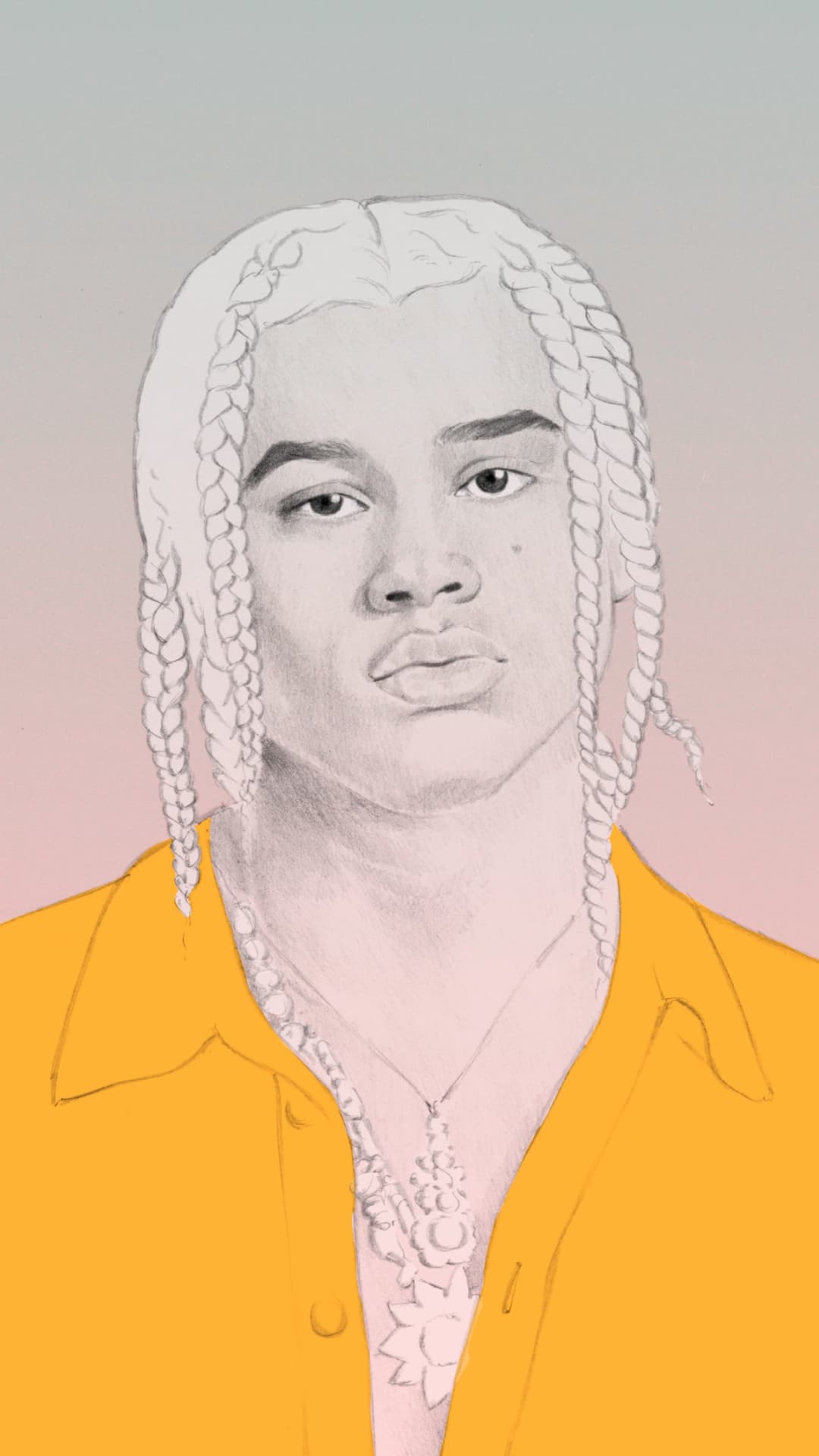

How 24kGoldn Went From Selling Shoes to Ruling Spotify

Twenty-year-old Golden Von Jones — AKA 24kGoldn — is a rap star and TikTok king. His single “Mood” has racked up a billion-plus streams and hit #1 on Billboard’s Hot 100, Rock, Alternative, and Rap charts — a first. The root of his success? Hustling sneakers.

Wealthsimple makes powerful financial tools to help you grow and manage your money. Learn more

I grew up in San Francisco, one of the world’s most expensive cities. The poverty line is around $100,000. So if your family makes less than that a year, you’re struggling to get by. My parents usually worked two or three jobs at a time, and had all sorts of side hustles. We could have lived somewhere cheaper. But, for them, raising me and my sister in a city rich with art, music, and culture was more important than having free time or less financial stress.

When I was a kid, to build my savings, my parents booked me modelling gigs, mostly for commercials and catalog shoots. They taught me basic financial literacy, and were extremely transparent about my money. I always knew how much I made, how much they set aside for my college fund, and how much I could spend. If I wanted to hit GameStop and buy a video game, I was free to do that — within reason.

When I was 10 or 11 years old, a kid walked into my English class rocking these black-and-white Air Jordans. Damn, I thought, I didn’t know shoes could be so fly! I’d only worn cheap sneakers from Ross or Big 5. His were the Jordan 11 Concords. I was obsessed. But when I asked my parents if I could buy a pair, they were like, “Fuck no. You trippin’, son!” Nobody should pay that much for sneakers, they believed. So I had to finesse my way into the sneaker game.

At 18, I was about to make more money than my parents pulled in a year, combined.

My cousin gave me a pair of old Air Jordans, but they were two and a half sizes too big, so I traded them on Facebook for another pair. But the shoes showed up in awful condition. But through that I learned, with paints and conditioners and some time and care, you can bring old sneakers back to life.

Sign up for our weekly non-boring newsletter about money, markets, and more.

By providing your email, you are consenting to receive communications from Wealthsimple Media Inc. Visit our Privacy Policy for more info, or contact us at privacy@wealthsimple.com or 80 Spadina Ave., Toronto, ON.

I became a real businessman. I started buying beat-up sneakers, fixing them, and selling them for three or four times what I’d paid. Then I started buying high-demand new releases for, say, $150 and flipping them for $400. I’d hit sneaker conventions with my friend Paypa Boy and take the train two and a half hours across the Bay to sell a pair to someone in a parking lot. It was a crash course in economics and investing. The more money I made, the more I invested in sneakers, building up my assets. By 10th or 11th grade, I was making at least $20,000.

I’ll be honest: in high school, I started selling weed, along with sneakers and clothes. My family lived in Lakeview, one of San Francisco’s last ‘hoods. But I went to Lowell, a sort of fancy high school in the Sunset neighbourhood. It was easy to buy drugs in places like Lakeview, then sell them elsewhere at a big markup. Fortunately, before I got too deep or in too much trouble, I discovered a new outlet for my energy: music.

At first, my friends and I would chill and rap on YouTube beats for hours. As time went on, I did most of the rapping. My friend Paypa Boy had a makeshift recording studio that he let me use for free. But I knew if I wanted to really blow up, I needed to step up my songs’ recording quality.

I found a nice studio that charged $35 an hour. I spent hours practicing my songs at home. Then I would go in, record, mix, and master an entire song in just three or four hours. A completed song would cost me about $135. Then I would upload it for free on SoundCloud and let it rock.

Soon all the money I made from selling sneakers and clothes went to music. I paid for a SoundCloud Premium subscription, to get detailed fan analytics, and I sunk money into blog promotions and SoundCloud reposts. And soon enough, I saw little returns on my investment. First, another artist offered me $250 to record a “feature” — basically, a rap verse for a song. As I gained more followers, the offers increased — $300, $500, $1,000. I was like, Wow, you mean I can go to a studio, rap for 30 seconds on someone’s song, and get 1,000 bucks? I can get used to this!

Recommended for you

She Was Living in a Shelter Six Years Ago. Now She’s the CEO of Her Own Beauty Company

Money Diaries

How to Quit Your Job and Bike Around the World for $17,000

Money Diaries

The World Wouldn't Make a Place for Angelica Ross. So She Made One for Herself

Money Diaries

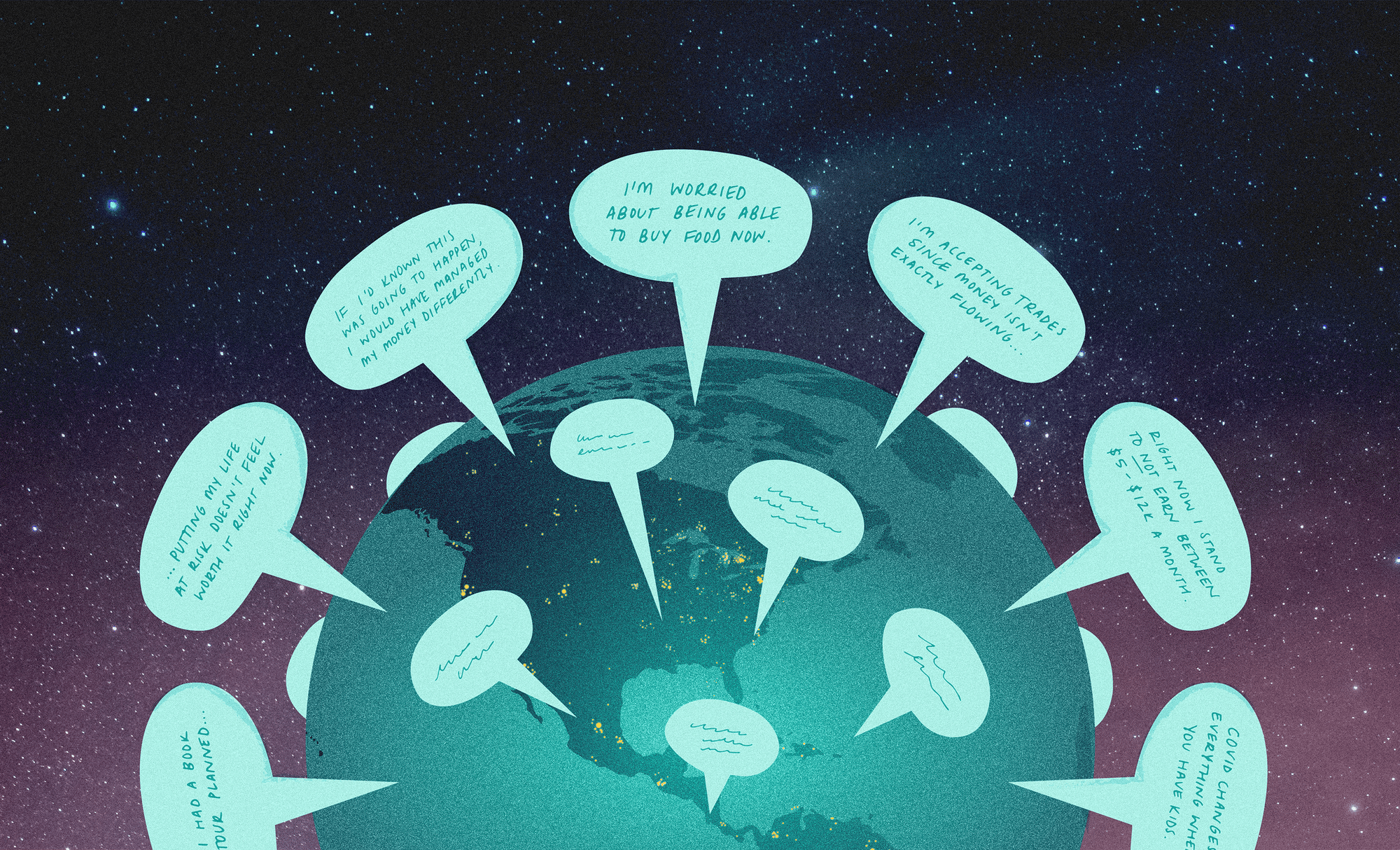

Pandemic Money Diaries — Panic at Trader Joe’s Edition

Money Diaries

After high school, I went to USC, in Los Angeles, on scholarship. I planned to major in business. But one day during my freshman year, I got a call from a number I didn’t recognize. It was the record exec Barry Weiss. “Hey,” he said, “I heard your song ‘Valentino.’ It’s gonna be a hit. I want to sign you to my record label. Come to New York!”

So I did. I had less than $100 in my bank account, and suddenly there was a six-figure record deal in front of me. The label offered me $50,000 to sign the agreement, and another $50,000 when I completed my first album — $100,000 total. At 18, I was about to make more money than my parents pulled in a year, combined. What am I going to do with all this money? I thought.

Once the first payment hit my account, I couldn’t help but go a little crazy. Yo, I’m a rapper now, officially! I thought. Let’s get fly! Let’s go to the club! But I also set a strict budget for myself. My contract helped with that.

Often labels offer an artist a ton of money upfront, but then they’ll own everything the artist ever makes. That’s because that up-front money is really an advance against future profits — a loan of sorts. And you pay back that loan with royalties and publishing rights. Many wildly successful artists end up broke because they burn their cash, owe their labels money, and never see any royalties. To avoid that, I asked for less money upfront and a small, short-term contract, because I felt sure I could prove myself on the first record, then make big money on my next one.

Once I got signed, I didn’t stop hustling, either. When I recorded “Mood,” I hooked up with TikTok influencers, and spent a couple thousand bucks to run my own marketing campaign, in addition to the label’s. I believed in the song, but I never expected that it would become one of the all-time biggest hits.

It’s strange to enjoy the kind of success I’ve had over the past year without it translating into millions and millions of dollars. No one buys CDs anymore; no one buys albums online; no one buys ringtones. Everyone streams. But streaming is tough on artists: your album has to be streamed something like 1,500 times for it to count as a single sale.

During a pandemic, another major revenue stream dissipated: touring. Fortunately, my team is savvy about finding ways to capitalize on my success, like with brand deals and other promotional opportunities. I’ve also recorded some high-paying features. The last one paid me $175,000. It’s a song for an EDM pop artist due out later this year. I’m sure I might look back one day and think, Damn, I don’t know if all these features were 100% in line with who I want to be as an artist. And yet the money was important, especially during the pandemic.

Investing in myself has led to the kind of success I had once only dreamed about. What makes me happiest now is helping out my parents. I owe everything to them, so it’s a thrill to pay them back for all the love and effort. They tell me that they don’t want my help, but I find ways to hook them up. Birthdays give me an excuse to go big and buy them new phones and other special presents. Sometimes I sneak a little bread into their bank accounts. They’re the reason I am who I am, and why I get to do what I do. Showing them love is the best way I can spend my money.

Davy Rothbart is an Emmy Award-winning filmmaker whose latest film, “17 Blocks,” will be released in 2021. He's also the creator of Found Magazine, a frequent contributor to NPR's “This American Life,” a bestselling author (“My Heart is an Idiot”), and the founder of Washington To Washington, an annual hiking trip for city kids. He lives in Los Angeles.