Money Diaries

A Nobel Peace Prize Winner on the Economics of Slave Labour

Kailash Satyarthi, whose organization has rescued more than 80,000 children from forced labour, tells his money story.

Wealthsimple makes powerful financial tools to help you grow and manage your money. Learn more

Wealthsimple is an investing service that uses technology to put your money to work like the world’s smartest investors. In “Money Diaries,” we feature interesting people telling their financial life stories in their own words.

Today, we hear from Kailash Satyarthi, Nobel Peace Prize winner and the subject of the documentary, “The Price of Free” — which won the 2018 Sundance Grand Jury Prize — about what started his decades-long mission to give children the right to a childhood.

I grew up in a small town called Vidisha, in central India. My family wasn’t poor, but we weren’t rich, either. You might say we were lower-middle class. My father was a policeman, and my mother a housewife. At five-years-old, on my very first day ever going to school, I saw another young boy sitting outside the school gates. He was a cobbler’s son, and he called to my friends and I to see if we needed our shoes repaired. It was our first day of school and our parents had just given all of us new shoes, so we passed him by. But once I was inside, I couldn’t stop thinking about the boy.

All of my friends and relatives went to school. But this boy … this boy did not. It was baffling to me. I asked my teacher, “Why is a child outside the gates and not with the rest of us here in the classroom?” She looked at me and said, “Oh, calm down. Calm down! Poor children have to work. It’s normal.”

But this still made no sense to me. I asked the principal the same question, and again received the same response. When I got home, I asked my parents, and then their friends. Everyone said the same thing: This is normal. But every morning and afternoon, entering school and leaving at the end of the day, I saw the same boy, calling out for business beside the front gates. To me it seemed clear that this was not normal. And that made me angry.

Sign up for our weekly non-boring newsletter about money, markets, and more.

By providing your email, you are consenting to receive communications from Wealthsimple Media Inc. Visit our Privacy Policy for more info, or contact us at privacy@wealthsimple.com or 80 Spadina Ave., Toronto, ON.

One day, I saw the child’s father working alongside him, on the doorstep of my school. I asked them: Why is this boy out here working, when the rest of us kids are inside? The boy was shy. He was the same age as me, just five or six years old. He didn’t know what to say, but his father, the cobbler, responded, “I never thought about it. My grandfather, my father, and I, all started working when we were children. Some people are just born to work.”

It has always seemed an obvious injustice to me for any child to have to lose their childhood and freedom in order to work. The spark that was lit inside of me that day has carried me through a decades-long struggle to fight for the rights of children.

I found that idea shocking. Why would some people be “born to work,” just because they’re from a particular community, a particular caste, a certain country, or they're a certain race or gender. I told the man that I rejected the idea of any child being “born to work” — and I still reject the idea sixty years later.

It has always seemed an obvious injustice to me for any child to have to lose their childhood and freedom in order to work. The spark that was lit inside of me that day has carried me through a decades-long struggle to fight for the rights of children. Right now, globally, over 152 million children are working full-time jobs.

A cobbler asking his five year old son to work alongside him is troublesome, but in India the problem is often much more sinister. Child slavery is rampant. Some kids are simply kidnapped and brought to mines, factories, and agricultural jobs. But often, here’s how it unfolds: A “recruiter” will visit a rural village, saying he’s looking for children to hire at a factory in the city. The children’s parents, destitute and jobless themselves, might unwittingly offer their children, believing it’s a legitimate and worthwhile opportunity. The recruiter might pay a month’s wages up front — 1,000 to 2,000 rupees ($12 to $25) — and promise that more money will be on its way once the child begins to work. After a week in the village, the recruiter returns to the city with dozens of kids in tow.

Of course, the factory never intends to pay the kids for their work, nor return the kids to their parents. They become slave labour. Sometimes the kids might earn 50 rupees a week, which is less than a dollar. And they’ll have to use that money to buy themselves food on supervised visits to a food stall. It’s indentured servitude, essentially. Imagine being a seven or eight year old and having to think about what you need to buy from a food stall each week to sustain yourself — it’s harrowing.

Recommended for you

Over time, the children are brainwashed by their handlers. They think that their parents are continuing to be paid as they’re working. The factory managers tell them, “We’re sending money home every week. This is a great thing you're doing. You're helping your family." It's heartbreaking because many of the kids take so much pride in their work. They think that they're doing something meaningful for their family, providing opportunities for their parents, their siblings, and themselves, when in fact their family isn't getting anything. The details are diabolical. Kids are told that back home their mother or grandmother is ill. “You have to work extra hard this week to pay for the medicine,” the handlers tell them. “Otherwise, they will die.” Every week, it’s a different story.

Meanwhile, the families may eventually realize they’ve sold their children into slavery, but they feel helpless, complicit, and ashamed. The local police are often bribed by the abductors and offer little help. Parents feel they have nowhere to turn.

My organization, the Kailash Satyarthi Children’s Foundation, takes political action to combat child slavery worldwide and also takes direct action — organizing raids on factories we believe are employing and enslaving child labourers. Over the years, we’ve freed more than 80,000 children.

What’s striking is how many of the kids, upon rescue, think that they’re the ones in trouble. This is part of their brainwashing. Their handlers reinforce the notion every day that the police and other outsiders have ulterior motives, filling them with outlandish ideas. “Someone will come to take away your kidneys, scoop out your eyes, and sell them on the black market,” the children are told. “Nobody from the outside is to be trusted!” When we arrive to rescue them, the kids often hide in fear, or lie about their circumstances.

The problem goes far beyond India. Child slavery exists and flourishes in at least 150 countries, everywhere from Brazil, Nigeria, and the Philippines, to the United States. At the root of the problem is a global demand for cheap goods and a willful ignorance as to the source of these goods.

We always bring local police along on our factory raids, to provide protection and to hopefully arrest the factory workers who are helping to enslave children. But since the police are so often corrupt, widely accepting bribes, our team never tells the police in advance where exactly the raids are going to take place. It’s not until moments before we arrive at a factory that the police find out which place we’re raiding.

Beyond the factories, many young girls are trafficked for prostitution. Traffickers must invest more money to bribe local police, who understand what they’re up to. But their profit is also multiplied. It might cost a “recruiter” 250,000 rupees (about $3,000) to pay off local police and offer an upfront payment to a girl’s family. Of course, the recruiters never say that they are taking the girls for prostitution; no matter how economically desperate the parents might be, nobody would send their girls away, if they understood their fate. Instead, the recruiters say that they are bringing the girl to a good job and a good life as domestic help, where she will earn good money every month. The parents are hungry for opportunities for their children; they may be uneducated or simply naive, and are easily deceived. A life of well-paid, well-treated domestic labour is an appealing fantasy. But once they leave the village, the recruiter sells the girl for $4,000 to a brothel keeper. The outcomes are grim.

Child slavery is obviously morally outrageous, but for those who enslave children, the economic incentives are easily apparent. My organization broke down the numbers: If an employer is hiding ten children in a small factory, and paying them nothing, their only cost might be 20 to 30 rupees (40 cents) per day, just to cover food. They might also hire an adult to oversee the children. Compare those costs to hiring ten adults to do the work. Even at minimum wage, they’d be paying four or five dollars a day for the same amount of work. Multiply those savings over weeks, months, and years. And think about the mines, farms, and factories that “employ” 100 or 200 or 500 children. These captors have all of the profit, with none of the labour costs. It’s like printing money.

The consequences are dastardly, not only for the enslaved children, but for the countries who permit it. When a country’s children are labourers, enslaved or not, you are denying these children an education. And you cannot be an equal partner in the globalized economy without an educated work force. So, if a large number of children are enslaved or working, it means you are denying the growth of the economy for that entire country.

The problem goes far beyond India. Child slavery exists and flourishes in at least 150 countries, everywhere from Brazil, Nigeria, and the Philippines, to the United States. At the root of the problem is a global demand for cheap goods and a willful ignorance as to the source of these goods. But we all have a say in the solution. As shoppers, we need to be conscious of the things we buy. When we see great deals, it’s our responsibility to ask questions and to pressure companies to be transparent about their supply chains; otherwise we’re feeding money into helping the problem persist. Companies need to know that we care, and that we’re not going to buy goods when child labour helped to produce it. We can use our voices — and our wallets — to create change.

Meanwhile, in India, our direct action raiding factories has begun to make a difference. We’ve had success stories — kids rescued from slavery who have later become doctors, lawyers, and even advocates for former child slaves, like themselves. With the right opportunities, any kid can flourish, no matter where they started. In a way, it all really connects back to that boy I saw outside my school when I was five years old — the cobbler’s son. I still think of him. What did his life turn out to be like? And how might his life have been different if he’d had the chance to walk into that school alongside my friends and me?

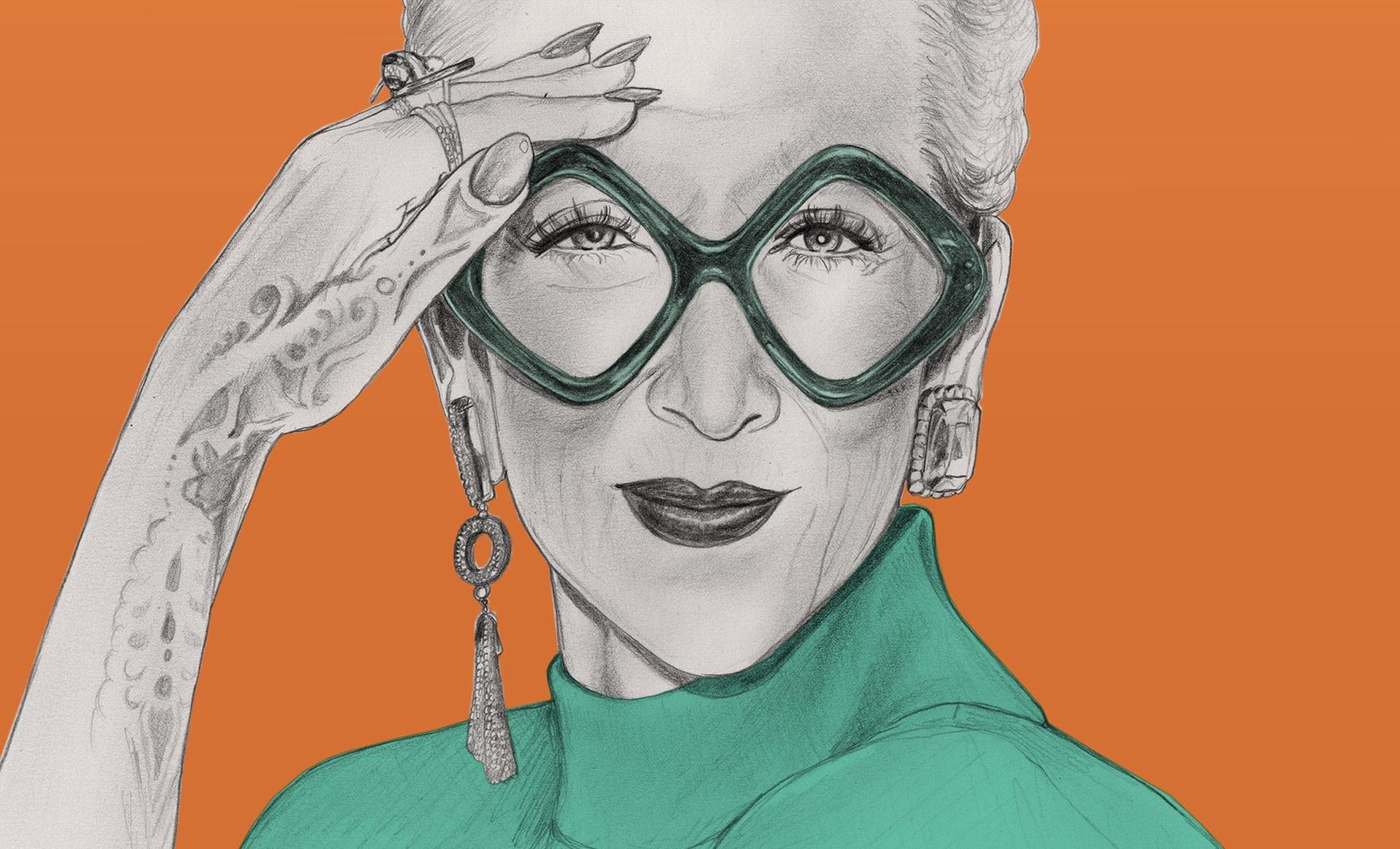

As told to Davy Rothbart exclusively for Wealthsimple; transcript edited and condensed for clarity. Illustration by Jenny Mörtsell.

Wealthsimple's education team is made up of writers and financial experts dedicated to making the world of finance easy to understand and not-at-all boring to read.