Money & the World

TVs Are Dirt Cheap. Food Is Super Expensive. Why?

A consumer mystery explained.

Wealthsimple makes powerful financial tools to help you grow and manage your money. Learn more

You don’t need to read the business pages to know a very basic (and lousy) economic fact: that nearly everything in Canada has gotten wildly more expensive over the past few years. Inflation peaked in 2022, but most stuff we buy still costs about 20% more than it did in 2020. The bitter cherry on top is that food prices are accelerating again. According to the latest data, restaurant prices are up 12.3% year-over-year, while groceries have risen by 7.3%. That’s more than double the U.S. rate, and it’s the highest in the G7.

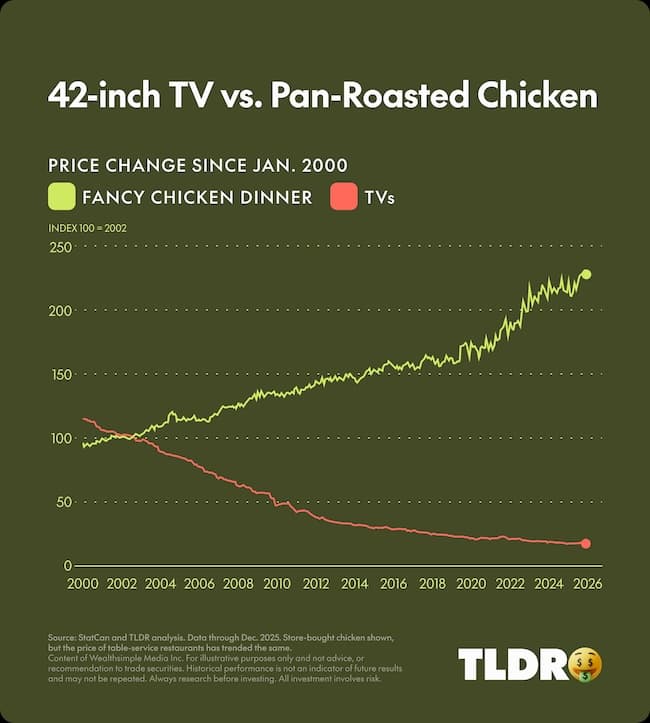

Here’s the really curious part: while food prices have soared, some products have gotten way cheaper, especially if you zoom out over the past 25 years. For instance: TVs. And the reasons reveal a lot about our changing economy. Let’s start with dinner.

It wasn’t so long ago — 2001, to be precise — that a 42-inch TV cost C$11,775. That was the sticker price for a cutting-edge Philips plasma, which would be about $20,000 in today’s money. So if you wanted to watch Bono belt out “It’s a beautiful day!” during the Super Bowl halftime show on a not-even-particularly-big screen, you more or less had to be rich. Now you can grab one for $250 — a 97% price drop.

Do you know what hasn’t dropped by 97%? A fancy chicken dinner for two at a nice restaurant. Since 2000, the price of such a meal is up nearly 140% — though we’re pretty sure chicken doesn’t taste 140% better. And if you add dessert and a nice bottle of wine, you would save money if you stayed home and bought a new TV instead.

Two more quick examples:

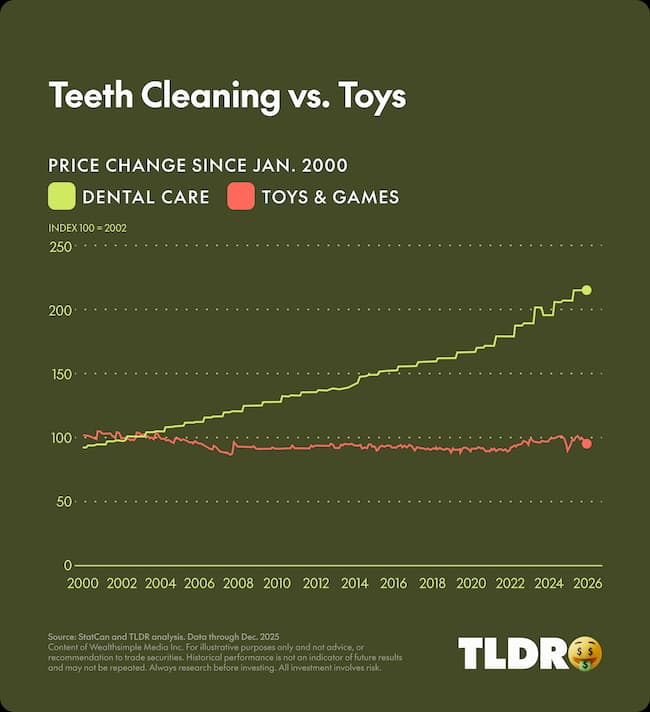

Toys are a tad cheaper than they were two and a half decades ago — about 6%. Good news for parents! The bad news? When your sweet, radiant klutz of a child falls and chips his tooth on his affordable new toy, your dentist bill will be more than twice as much — +134% — as it would have been back when 42-inch TVs cost five figures.

OK, one more:

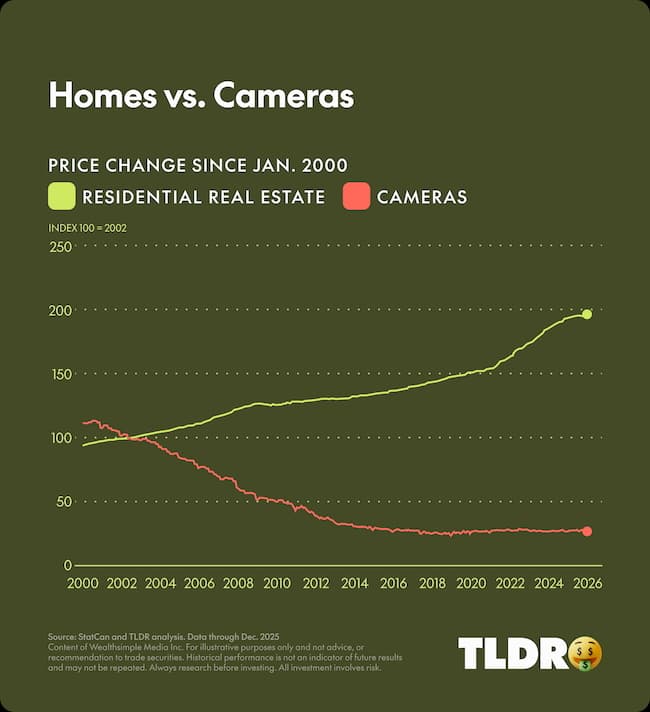

Breaking news: housing is expensive! The average Canadian home costs twice as much as it did in 2000. The teeny-tiny silver lining? If you are somehow able to buy a place, you won’t have to pay much for a camera to take a photo of it for Instagram. Yay?

The Story Behind These Trends

It’s no secret why tech gadgets have gotten cheaper

Writer/engineer Brian Potter recently published a captivating essay about the hyper-efficiencies of TV manufacturing. The process involves etching tiny transistors into large sheets of glass and layering it, no kidding, with liquefied crystals. Companies have built billion-dollar factories to perform this miracle-adjacent work at scale and pump out millions of low-cost units. Semiconductor manufacturing has benefitted from similar technological gains, hence all manner of consumer tech goods have plunged in price.

You can blame an economic phenomenon for your pricey chicken

Keen readers probably noticed that pan-roasted chickens, dentist visits, and homes all share something in common: they’re service-intensive. And it’s hard to make service workers more productive. Sure, PCs and email have boosted office-worker efficiency, but technology hasn’t made dentists faster at cleaning teeth or construction workers quicker at framing houses. And yet service-industry workers get pay bumps over time anyway, since they exist in the same labour market as workers in industries that are more productive and profitable. Think of it in terms of keeping up: if a sharp young grad can make $200,000 in tech, a dental clinic has to offer competitive wages to attract talent. And these rising labour costs get passed on to customers in the form of higher prices. There’s a name for this economic phenomenon: “Baumol’s cost disease.”

Baumol’s cost disease is especially pronounced in wealthy nations, like Canada and the U.S. Over the past 25 years, as consumer tech got cheaper to produce, tech companies grew increasingly profitable and started paying their employees more. These jumbo salaries put upward pressure on wages; banks, hospitals, and law firms all had to pony up. And the wage race quickly rippled out into industries that weren’t even chasing the same talent. When Big Tech engineers in Toronto and San Francisco started pulling mega-salaries, they drove up real-estate prices. Restaurants, in turn, had to raise wages so their own employees could afford their increasingly high rent, and menu prices reflected these costs. And that’s why a burger will set you back at least $18 now.

So will housing or dentist visits ever get cheaper?

Housing might! But it’ll likely require a leap in innovation — scalable 3D-printed houses, say, or robots that can do precision manual labour. Unfortunately, it’d be hard to speed up teeth cleaning more than we already have, and we’re a long, long way from automating it. That means any price relief would likely have to come from a different part of the equation — e.g., expanded government-subsidized dental coverage. Until robots learn how to scrape plaque off teeth or hang drywall, we’ll likely be stuck in this peculiar economy where you can afford a giant TV on which to stream any movie ever created — true magic! — but you can’t afford a root canal or a new apartment. Progress is weird like that.

—Dan Xin Huang. Charts and data by Brennan Doherty.

Wealthsimple's education team is made up of writers and financial experts dedicated to making the world of finance easy to understand and not-at-all boring to read.